All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Examining the Interplay of Social, Cultural, and Personal Factors in Shaping Students’ Perceptions of Female Condom Usage: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Introduction

A systematic review focused on students’ perceptions was aimed at examining how social, cultural, and personal factors influence female condom usage among tertiary students. Female condoms prevent unintended births among young people; however, they appear to be misunderstood compared to male condoms. The objective of this review was to examine how social, cultural, and personal factors influence female condom usage among tertiary students. The researcher’s purpose was to find if there is a gap that needs to be addressed in relation to the use of female condoms.

Methods

The researcher searched three purposely selected databases: PubMed, ProQuest, and Google Scholar, from 2013 to 2023. This study used the PRISMA framework to guide and ensure reproducible reporting of the review process. This study identified seven themes from the findings discussed. The CASP was used for study appraisal. This study reviewed a total of seven studies. The thematic analysis was used to study the trends in the articles from the data extracted and to develop themes.

Results

This study identified seven themes from the findings discussed. The use of condoms by women is impacted by socio-cultural elements such as gender norms and attitudes. Due to poor student use, cultural stigma, societal expectations, and male resistance, female condoms are not widely accepted, even though they are effective in reducing HIV, STDs, and unintended pregnancies.

Discussion

This study reveals that a number of factors, including discomfort, insertion difficulty, poor access, and negative perceptions, cause low utilization. The results indicate that, in order to improve access and education, gender norms must be challenged, and culturally responsive practices must be promoted. However, the study’s narrow focus means it requires a more extensive, inclusive investigation.

Conclusion

This review highlights how cultural norms, gender dynamics, and social and personal barriers continue to restrict the use of female condoms among female students, despite their demonstrated efficacy. In order to overcome these obstacles and encourage broader use of female condoms in higher education settings, culturally aware, education-based interventions and inclusive public health strategies are necessary.

1. INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections and the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) are two major issues affecting South Africa [1]. South Africa’s high rate of HIV/AIDS and unintended pregnancies among young people poses a serious threat to public health [2]. Women make up around 60% of those living with HIV worldwide, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa [2]. The majority of mortality among women between the ages of 15 and 49 is caused by HIV-related infections [3]. The fact that Africa’s Sub-Saharan Region (SSA) is the world’s most disadvantaged and lowest-income region may impact this. South Africa’s nationwide public sector condom distribution project is a response to the HIV epidemic and sexually transmitted infections.

Lasse Hessel first introduced the female condom in 1984 [3]. He developed it in response to information that women had few options for taking complete responsibility for their health to prevent HIV/AIDS [3]. Condoms, both male and female, are provided free of charge under the South African public health system. According to several surveys, the majority of young South Africans are aware that one of the best dual methods for preventing HIV, STIs, and unexpected pregnancies is the use of female condoms [1]. Female condom usage and prevalence are still lower than those of male condoms; therefore, HIV prevalence and unplanned pregnancies among young people remain difficult to reduce [2]. There is a concomitant rise in STI rates among university students and an upsurge in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS [4]. The high HIV prevalence among young individuals aged 15-24 in 2012 was 7.1% [5]. This indicates that persons in this age range have a higher risk of contracting HIV due to their potentially hazardous lifestyles and sexual behaviour.

Over 200 million women worldwide face barriers to accessing family planning [6]. Sexual pressure, influenced by factors such as age, sex, and peer pressure, significantly affects women’s use of contraceptives despite the availability of effective alternatives [7]. There is evidence that culture has both beneficial and detrimental effects on sexual health, as the beliefs and values that individuals express through their expectations in heterosexual relationships, with males being given tremendous power [8]. Women’s reproductive health concerns may not be fully understood due to the dominance of male condoms in the market, and the supply and uptake of female condoms [9]. Despite awareness of the benefits of female condoms, their acceptance among Nigerian youth, particularly those in tertiary institutions, remains low [10]. This study highlights the interaction between social, cultural, and personal factors in shaping students’ perceptions of female condom usage and how it leads to low utilization of female condoms. The purpose of this review was to thoroughly analyse and compile the data that is currently available on the variables affecting female condom use among students, with an emphasis on the ways in which cultural, social, and individual factors affect attitudes and actions. By filling this gap, the review hopes to guide focused interventions and policies that can improve the autonomy of female students’ sexual health and their ability to negotiate condoms. A systematic review was very important in this study as it helped ensure reproducibility and transparency and lessen the bias of the evidence found in this study.

2. METHODS DETAILS

The researcher used PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) to structure the review. The researcher conducted a search of three purposely selected databases: ProQuest, Google Scholar, and PubMed. Exact keywords were used to retrieve studies from these three databases. The first set is “student,” which was used so that studies that are found would be based on the population of students; the second set is “tertiary institution,” where all the studies should have been conducted at a tertiary institution. The third word used is “perception”; the researcher wanted to find the variety of perceptions the students have with regard to female condoms. The last word is “female condoms,” to have the studies focus on female condoms rather than perceptions of male condom usage. The keywords used gave the outcomes of a small pool of publications: (“student” and “female condom” and “perception” and “tertiary institution”). Limits were applied to the database instrument to conduct investigations under eligibility criteria. English was used as a limit. The researcher started by including studies conducted in the past five years as a limit. However, only a few studies were found. The researcher then decided to expand the limit to 10 years (2013–2023).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The researcher studied the research literature of explanations and evaluations of research that involved or included perceptions of students on female condoms. The literature included in this study is relevant to the interplay of social, cultural, and personal factors in shaping students’ perceptions of female condom usage. Only studies that were conducted in the English language were included in this study.

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- The study must be published in English.

- The study must have been conducted between 2013 and 2023.

- The study must include the perceptions of students on female condoms.

- The study must be focused on the population of tertiary students.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- The researcher excluded all studies that do not address or discuss female condom use among students or are at high risk of bias.

- Studies conducted before 2013, even if they focused on the interplay of social, cultural, and personal factors in shaping students’ perceptions of female condom usage.

- Articles published in languages other than English.

The researcher chose a specific period to ensure the current relevance of the systematic review and to ensure that the overall knowledge of female condoms remains up to date, since there has been a change in tertiary institutions regarding sexual health. This is due to the Department of Health and the stakeholders involved in sexual health in tertiary institutions continuously addressing the challenges associated with sexual health.

2.2. Study Selection

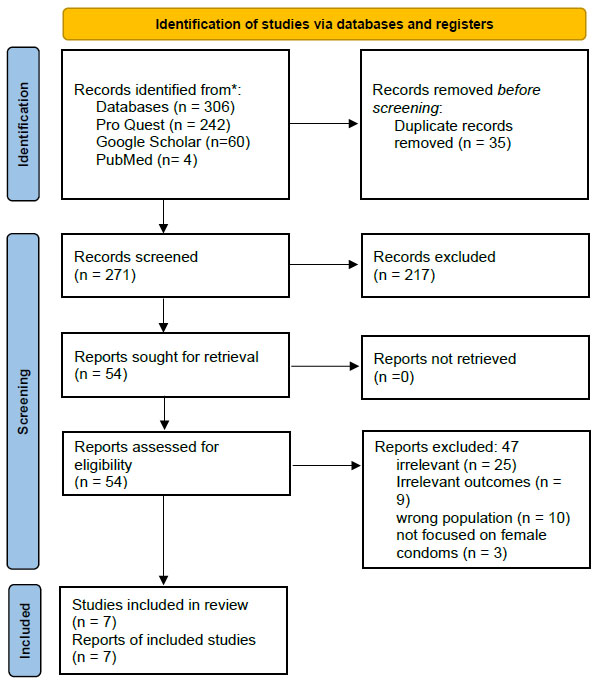

The researcher followed the PRISMA guidelines and used PRISMA to generate a flow diagram to conduct the systematic review [11]. The diagram was used to select which research would be included. The review was conducted using exclusion criteria. Fig. (1), modified from the PRISMA flow diagram generator, depicts the study selection process.

2.3. Study Selection Criteria

The database search yielded 306 studies from Africa, which the researcher transferred to Covidence software to simplify screening and data extraction. The results from the databases were: 242 studies from ProQuest, 60 from Google Scholar, and four from PubMed. The software removed 35 duplicate studies from the database, and then 271 studies were screened by abstract for relevance to the review. Studies were included for full-text screening, where 54 were included and 217 studies were excluded. After the full-text screening, seven studies were eligible for data extraction, and 47 were excluded.

2.4. Appraisal of the Selected Studies in this Research

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) was used to evaluate the selected papers [12]. The researcher used the CASP method to include the selected studies, assess the articles, and ensure their significance and credibility. The cohort study checklist was used to evaluate the articles’ relevance, solidity, and credibility. The cohort study checklist was used for cross-sectional study designs. The studies that matched the checklist were then integrated into the review. The checklist contained twelve questions. The researcher divided the total number of “yes” scores by the total number of questions. The results were then shown in Table 1 as percentages. The qualitative checklist was also used for studies such as exploratory designs. This checklist contained ten questions. The researcher divided the total number of “yes” responses by ten and converted it into a percentage.

Prisma Flow Diagram.

2.5. Characteristics of the Studies

The researcher extracted data by comparing the information that was collected. Data was extracted, analysed, and retrieved from all the research that satisfied the requirements. As stated in the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the researcher chose a period from 2013 to November 2023 to ensure the current relevance of the literature and to ensure the overall knowledge of female condoms remained up to date. The details extracted from studies included the authors, the year of release, the title of the topic, the location where the study was undertaken, the sample used in the study, the type of study, and the findings. Table 2 exhibits the characteristics of the studies. Data were extracted using a standardized form to guarantee consistency across studies, and where feasible, missing statistics were estimated using the information that was available. While quantitative data was standardized through simple conversions to enable comparison, qualitative findings were thematically coded. Studies with insufficient data were not included in the comparative analysis but were included in the narrative synthesis.

2.6. Thematic Analysis of The Selected Studies

The researcher used thematic analysis to analyse data using the methods or steps highlighted previously [6]. The following steps were followed to identify themes, and also helped in interpreting data:

2.6.1. Familiarisation with Data

The researcher read and re-read all seven studies included, focusing on their findings so that he could familiarise himself with the data and facilitate easy interpretation of the findings.

2.6.2. Generating Initial Codes

The researchers coded all interesting features across all seven studies through the use of data extracted from Excel. The codes included partner stigma, culture perception, discomfort, peer perception, gender norms and barriers.

2.6.3. Developing Themes

The researcher combined all the codes that were similar and placed all the codes that formed the pattern. Five themes were developed.

2.6.4. Reviewing Themes

The researcher, with the supervisor, reviewed and ensured that all the coded items were available in all the themes; some of the coded items were eliminated.

2.6.5. Defining and Naming Themes

The researcher named all the themes and ensured all coded patterns were placed under one subject. The themes are five, which are: the impact of socio-cultural factors on the usage of female condoms; socio-cultural issues that influence female condom use; perceptions towards female condoms at institutions of higher education; challenges with the use of female condoms; and female condoms at institutions of higher learning. The researcher will also verify whether the data shows a consistent pattern.

2.6.6. Interpretation and Reporting

The researcher created a final report below as a result, giving a detailed view and also showing the theme’s significance.

No formal sensitivity analyses were conducted in this review. The researcher refined and reviewed these themes and finalised the thematic framework of the research as follows.

The themes are:

- The impact of socio-cultural factors on the usage of female condoms [13-15].

- Socio-cultural issues that influence female condom use [3, 13-16].

- Perceptions towards female condoms at institutions of higher education [3, 13, 15, 16, 18].

- Challenges with the usage of female condoms [17, 14, 18, 13].

- Female condoms at institutions of higher learning [13, 14, 17, 18].

These subheadings provide the reader with a clear and concise overview of the research on female condoms that is the subject of this inquiry. Several knowledge gaps on the topics that surfaced throughout the analysis are indicated above, based on the results of this systematic literature review study. However, recently published studies have not entirely addressed the social, cultural, and other aspects that influence the use of female condoms. Condensed into a summary of the research findings, Table 2 indicates the number of studies that reported particular outcomes for this corresponding journal review article. Using guidelines from the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach, which was modified for the qualitative and mixed-methods nature of the review, the degree of certainty of evidence for each outcome was evaluated. This required assessing the reliability, coherence, and generalizability of study results.

Table 2.

| Name of author/Ref. | Title | Year | Country | Methodology | Sample size | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shiburi. [13]. | The subject of the study is "the perceptions of postgraduate students about female condoms at the University of Limpopo" (Shiburi, 2021). | 2021 | South Africa | Qualitative research | 10 | • Easy access and lack of availability, as well as inadequate knowledge or experience using condoms among students, were the findings of this study. • The best way to use female condoms is not well understood. One barrier is the stigma from society and culture. Insertion requires a great deal of time and work. |

| Boraya et al. [15]. | The subject of the study is "Utilization of the female condom among Youths in selected Tertiary Training institutions in Migori County, Kenya" (Boraya, 2019). | 2019 | Kenya | Quantitative and qualitative | 385 | • Their demographics and accessibility obstacles influence women's use of condoms. Culture and religion have an impact on how women use condoms. |

| Ndlovu et al. [16]. | The subject of the study was "University of Johannesburg’s Postgraduate Students’ Perceptions and Awareness of Safe Sex Services and Activities" (Ndlovu, 2019). | 2019 | South Africa | Qualitative approach | 8 | • Availability and access to female condoms. • Power and control as prevention measures. |

| Tobin-West et al. [17]. | The subject of the study was "Awareness, acceptability, and use of female condoms among university students in Nigeria: Implications for STI/HIV prevention" (Tobin-West et al., 2014). | 2013 | Nigeria | Quantitative | 770 | • Obstacles to the accessibility, cost, and simplicity of insertion of female condoms were the findings of this study. |

| Shitindiet al. [18]. | The subject of the study was "Perceived motivators, knowledge, attitude, self-reported and intentional practice of female condom use among female students in higher training institutions in Dodoma, Tanzania” (Shitindi et al., 2023). | 2023 | Tanzania | Quantitative research | 384 | • Inadequate knowledge about and use of female condoms. • A tiny percentage of respondents said that they intended to resort to female condoms and had a good understanding and favourable attitudes. |

| Obembe et al. [3]. | The subject of the study was "Perceived confidence to use female condoms among students in Tertiary Institutions of a Metropolitan City, Southwestern Nigeria" (Obembe et al., 2017). | 2017 | Nigeria | Quantitative | 388 | • Few people seem confident enough to use a female condom. Perceptions about the device significantly impacted the confidence to wear a female condom. |

| Mnguni [14]. | The subject of the study was "Probing the sociocultural factors influencing female condom use among heterosexual women in Clermont, Durban" (Mnguni, 2016). | 2016 | South Africa | Qualitative research | 19 | • The perceived advantages of female condoms affected both men's and women's acceptance and continued use of them. Talks on safer sexual practices and the ability of women to navigate them are open and welcomed by males. |

3. RESULTS

The five topics were created from the articles chosen for the study that discussed the factors that influence student perception of using female condoms.

3.1. The Impact of Socio-cultural Factors on the Usage of Female Condoms

The female condom is a multipurpose preventative instrument with a clear covering that is intended to protect people against HIV, unintended pregnancies, and other STDs [19]. To prevent HIV, STDs, and unplanned pregnancies, female condoms are a valuable and efficient tool. Information taken from the 2014 Global Health Visions - Business Case for Female Condoms Report shows that using female condom distribution tactics has resulted in health advantages in countries such as Cameroon, Kenya, and Nigeria [20]. This was based on general population health indicators following the addition of the female condom as an additional method to the mix of contraceptive techniques. The South African government has endeavoured to enhance the accessibility of female condoms to the broader populace affected by the HIV/AIDS pandemic and to increase the range of contraceptive methods available to women [20].

The research refers to social, cultural, and behavioural requirements that characterise and define heterosexual partnerships. Culture is people’s social heritage and the ways they are taught to act, feel, and think, passed down from generation to generation, including the ways embodied in tangible objects [21]. Culture may have both a beneficial and a detrimental impact on people’s health practices. Gender and behavioural norms have been identified as barriers to the sustained and ongoing use of female condoms in studies on their adoption and use [8].

The appropriate way to apply a female condom depends on two consenting people. Several studies have reported that male attitudes influence the choice of female condom use [15]. A survey showed that 66.4% of males reported they disliked female condoms, and this has led females to shy away from female condoms, worrying about how their male partners will react when they find out about the condom [15]. Males who used female condoms said that they could stay longer during sex, which they appreciated, but others did not like that they could not stay long [14]. A South African survey found that most men prefer to use branded condoms rather than the inexpensive ones available at the clinic. They also denigrate individuals who use clinic condoms, which puts pressure on men who cannot afford branded condoms [14].

Culturally, the open purchase of female condoms is perceived as promiscuity, as stated by 85% of the participants in the study [15]. Some participants stated that initiating sexual matters is the male’s responsibility; this has led to women being submissive to their men and accepting any decision they make, thereby leaving their health at risk [15].

3.2. Socio-cultural Issues that Influence Female Condom use

Gender is a social and cultural construct that affects women’s behaviour in seeking health care and has implications for their access to HIV prevention programs. Cultural beliefs, conventions, customs, and traditions greatly influence an individual’s sexual behaviour. These factors can also impact decisions about fertility and expose individuals to risks such as sexually transmitted illnesses. As a result, socio-cultural factors are potent predictors of adopting health promotion strategies [13].

According to the report, males continue to significantly affect women’s decision-making when it comes to the use of condoms during sexual intercourse. This is mostly due to the fact that some women lack the self-assurance to bring up the topic of condom use with their spouses, even when they are accused of adultery. Additional factors include patriarchal beliefs around bride money payments, where males do not want to use condoms because they want their wives to satisfy their sexual needs [22]. Young women said that for a consistent partner to insist on condom use is perceived as a lack of respect and trust.

Violence against women has increased in all civilisations, making women more vulnerable to diseases and unplanned childbirth. In a marriage environment, African men appear to be less concerned with gender equality [23]. Gender inequality and power disparities, as a result, make women more vulnerable to sexually transmitted diseases and unintended pregnancies. Gender inequalities have been blamed on cultural, societal, and religious standards [24]. Polygamy is considered unscriptural, unbiblical, and thus not Christian [25]. One of the findings from the participants was that challenges faced by women in polygamous relationships included practising unsafe sex and being unable to make decisions regarding sex, which led to dry sex, causing damage to sexual organs [26].

Long-term partnerships are associated with a lack of condom use. Many couples reported using condoms at the start of heterosexual relationships, but usage frequently diminishes as the partnership develops [27]. This behaviour has also been observed particularly in teens. Due to the belief that a strong relationship guards against HIV and other STDs, this has been seen in couples who are married or in long-lasting relationships, where condom use is minimal or nonexistent [27]. Most African nations do not require couples to use condoms, as it is seen as an indication of adultery and a lack of trust [22].

3.3. Perceptions Towards Female Condoms at Institutions of Higher Education

Women often talk about the challenges they face when using female condoms. These challenges include men’s preference for the male condom, partner rejection, discomfort during sex, excessive lubrication requirements, trouble using the device, unease inserting the condom, shortage, affordability, and men’s distaste for the appearance. Education is an important indicator of female condom usage [28]. People with both higher and lower educational levels use them, although those with lower education levels are still reluctant to do so. Perceptions and affiliations with religion also negatively affect the usage of female condoms [4].

People’s negative opinions of the female condom stem from their disapproval of the original design [2]. The present report states that new female condoms are being produced to replace the FC2, which is widely disapproved of. Even though the new condom is made of Synthex latex, it still has a bad image. One advantage of the new condom is its low cost [29].

In a study conducted in Kenya at selected tertiary institutions, 71.5% of students were found to be against female condoms, leading to the insignificant use of condoms [15]. Several studies showed that 89.3% were aware of female condoms, while 76.5% demonstrated a fair perception, and 10.8% and 12.6% demonstrated excellent and poor perceptions, respectively, indicating the need to address these perceptions [15]. Research conducted in 2017 found that 41.7% of participants disapproved of the notion, and 39.7% of individuals would not feel satisfied using a female condom due to fears of adultery, while others were unable to support the female condom because of anger issues from their partners [3]. Culture rendered women docile, which has led to females feeling powerless to ask their male spouses for personal use of female condoms; they also trusted their relationships since their partners provided everything for them, which made females unable to communicate for safer sexual practices [14].

3.4. Challenges with the use of Female Condoms

The need for women to negotiate with male companions is necessary; however, this has encountered resistance due to socio-cultural demands prevalent in African cultures. Men use condoms more frequently than women, who reported finding it harder to use them because they had a more challenging time initiating use [30]. Women are not allowed to introduce condoms, either male or female, into their relationships because of men’s sexual and reproductive supremacy. Research conducted in 2015 claims that males are seldom the focus of female condom campaigns and have historically been disregarded as study participants in female condom studies [31]. In a sexual relationship, it can be challenging to discuss the use of a female condom as a preventative measure with male partners who often exhibit gender inequality and authority. Gender imbalances in a relationship, rather than a lack of knowledge, are among the main causes of risky sexual behaviours [32]. Despite their awareness, many female students choose not to engage in safer sexual practices because they are unable to discuss the use of protection with their partners out of concern that they would forfeit the advantages of their relationships [33].

Female condom utilisation was low at 3.7%; this was mainly affected by unavailability and the condom not being affordable [15]. According to a study conducted at the University of Limpopo in 2021, some students faced challenges because their residence entrance had a box of male condoms instead of female condoms; consequently, this led to only one type of condom being used [13]. In a different study conducted at the University of Johannesburg, participants acknowledged that few free female condoms were available on campus and even in public areas [16]. However, the majority of students recognized the value of female condoms in avoiding unintended pregnancies and STDs [16]. In addition, the product’s exorbitant cost, unavailability, and difficulty of insertion caused anxiety among both male and female students. Studies have reported that 90.3% of youth have difficulty inserting the female condom, while some have raised concerns that it needs to be worn for 8 hours, and others noted there is insufficient knowledge regarding female condom use [13, 15].

3.5. Female Condoms at Institutions of Higher Learning

Peers in higher education frequently influence students to engage in activities that society as a whole and their parents would not support [6]. Students at South African Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) institutions were surveyed, and the results showed that the students understood the importance of regularly using female condoms as a method of avoiding the spread of STIs and HIV [2].

According to demographics, young adults who are married are less likely than young people who are single to use female condoms [34]. Female students are able to negotiate condom use and see it as a means of preventing HIV transmission [30]. Some students seek transactional relationships or cash rewards from both sexual partners and relatives because they are dissatisfied with the financial assistance they receive from their guardians [15]. The majority of students receive financial aid from their legal guardians and parents [15]. Informal partnerships were prevalent among individuals who received support from partners and family.

4. DISCUSSION OF THE FINDINGS

The results of the systematic review highlighted the intricate interaction of societal, cultural, and individual elements that shape students’ perceptions of female condom use. The five themes identified illuminate various contexts and emphasize challenges and opportunities for increasing the uptake of female condoms across diverse cultural settings. Socio-cultural influences: Recognition of the female condom as a preventive tool against HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and unintended pregnancy highlights its potential public health benefits. Successful distribution strategies in nations such as Cameroon, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and other low-income countries suggest that strategic interventions can positively affect health indicators [35]. However, cultural factors, particularly the role of gender and behavioural norms, are significant barriers to women’s continued use of condoms [36].

Men’s attitudes and preferences: The influence of men’s attitudes on women’s condom use is an essential aspect of the discussion. The fact that a significant proportion of men reported disliking female condoms may lead to reluctance among women and highlights the need for targeted educational efforts. The preference for branded condoms over clinic-provided ones reflects broader societal perceptions that may contribute to the stigma against female condoms [37].

Cultural norms and perceptions: Cultural norms are essential in shaping women’s perceptions of condom use. The association between purchasing female condoms and promiscuity reflects deep-seated social attitudes [19]. Gender inequality further exacerbates the problem, leaving women vulnerable to disease and unwanted pregnancies [19]. Overcoming these cultural barriers requires a differentiated approach that considers both individual and societal perspectives.

University recognition: Challenges faced by women, including discomfort, partner rejection, and men’s preference for alternative contraceptive methods, highlight the complexity of promoting condom use among women [38]. Education level was a predictor, with higher levels of schooling associated with increased usage [39]. Addressing negative perceptions, especially among students, requires targeted interventions that consider both individual and structural factors.

Challenges in using female condoms: The imbalance between men and women poses a significant challenge in partnerships when discussing the usage of female condoms [36]. The following difficulties have been reported: issues such as poor access, affordability, and discomfort during sex highlight the need for comprehensive sexual health education [36]. Overcoming these challenges requires dismantling gender norms and addressing structural issues that impede accessibility.

Use and awareness: Low rates of female condom use are due to several factors, including lack of awareness, difficulty in insertion, and misconceptions about the duration of use [28]. Awareness efforts must also be accompanied by educational initiatives to address these misconceptions. Additionally, addressing issues related to insertion difficulty and the perceived prolonged usage time will help improve utilisation.

The impact of peer and interpersonal relationships in higher education: The effects of peer and interpersonal interactions within higher education institutions raise the need for targeted interventions in educational settings [32, 40]. Financial support and business relationships influence decision-making, highlighting the importance of considering socio-economic factors in promoting female condom use among students.

In conclusion, the results highlight the importance of considering and recognising socio-cultural nuances that influence women’s perceptions of condom use. Targeted interventions need to not only focus on raising awareness but also challenge deeply ingrained cultural norms, empower women to negotiate safe sex practices, and address structural barriers to access. A holistic approach that considers individual, interpersonal, and social factors is essential to promoting positive attitudes toward female condom use among students and the broader cultural context.

5. IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

The results underscore the need for targeted public health initiatives to encourage female condom use, particularly in regions with high HIV prevalence. Strategies should aim to dismantle cultural biases and misconceptions while addressing socio-economic barriers to accessibility. Given the influence of education on condom use, sexual health programs must be tailored to fill knowledge gaps and counteract negative perceptions [41]. Integrating comprehensive sexual health education within higher education institutions can empower students to make informed decisions and confidently negotiate safe sex practices.

Recognizing gender disparities in sexual health decision-making highlights the urgency of gender equality programs. These efforts should empower women to assert condom use and challenge prevailing social norms that perpetuate gender inequalities. Improving access to female condoms in healthcare settings is also crucial, ensuring availability, affordability, and ease of access, especially for students who face unique barriers in tertiary institutions.

Cultural norms significantly shape women’s perceptions of condom use [36], necessitating culturally sensitive campaigns that confront negative stereotypes and overcome cultural barriers. Engaging community leaders, influencers, and religious figures can enhance the reach and impact of these efforts. Moreover, interventions targeting couples and relationship dynamics are essential. Approaches that include couple-focused counseling and communication training can help address challenges such as discomfort, partner rejection, and preferences for alternative contraceptive methods [42].

Product Innovation and Marketing: Negative perceptions of female condoms, particularly regarding discomfort during intercourse, highlight the urgent need for product innovation [42]. Research and development should prioritize improving the design, usability, and overall user satisfaction to enhance acceptance. Alongside product improvements, effective marketing strategies that emphasize the benefits of female condoms are crucial to shifting public perceptions. Political advocacy plays a vital role in supporting these efforts, governments should integrate female condoms into existing contraceptive programs to ensure affordability while actively challenging gender norms that restrict access [32].

Future research should employ diverse methodologies and include a broad range of populations, taking into account factors such as age, socio-economic status, and geographic location. This inclusive approach will help fill existing knowledge gaps and deepen understanding of the complex factors influencing women’s perceptions and use of female condoms.

6. LIMITATIONS

The researcher focused exclusively on English-language articles from Africa; therefore, only English papers were included in this systematic review. Studies published in other languages or conducted on different continents were excluded, which may have limited the breadth and generalizability of the findings.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review highlights the complex social, cultural, and individual factors influencing female students' perceptions and use of female condoms. Despite their proven effectiveness in preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancies, female condom utilization remains limited due to persistent barriers such as stigma, partner resistance, and entrenched gender norms. These findings underscore the urgent need for targeted, culturally sensitive public health initiatives that address both interpersonal dynamics and structural challenges. Education continues to play a vital role in fostering positive attitudes and empowering students to make informed decisions about their sexual health. Future interventions should prioritize inclusive, evidence-based approaches that empower women and actively engage men to promote equitable sexual health decision-making. Moreover, further research is necessary to evaluate intervention-based studies focusing on community-led cultural transformations, couple-based counseling, and peer-led education. Longitudinal and multi-country studies are also essential to assess the impact of evolving societal norms, policies, and educational efforts on female condom uptake over time.

RECOMMENDATIONS

After thoroughly reviewing the findings, the researcher strongly recommends the implementation of multiple strategies to improve female condom usage. The Department of Health should develop gender-sensitive communication campaigns aimed at challenging prevailing gender norms. These campaigns could be effectively disseminated through student campus media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. Additionally, universities should appoint health facilitators to monitor condom distribution points in high-traffic areas, ensuring that female and male condoms are equally accessible and prominently displayed. Female condoms should also be made available in restrooms designated for both males and females. Furthermore, student counsellors and university health staff should actively participate in promoting female condom use. The researcher also emphasizes the importance of integrating comprehensive sexual health education into the university curriculum, particularly during the orientation programs for new students each year.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

M.C.R.: Conceptualization, methodology, and drafting the manuscript;. N.S.M.: Validated the results and proofread the manuscript;. All authors reviewed the findings and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| HIV | = Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| AIDS | = Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome |

| STI | = Sexually Transmitted Infection |

| STD | = Sexually Transmitted Disease |

| CASP | = Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| TVET | = Technical and Vocational Education and Training |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data included in this study were derived from published articles and dissertations that are already available online.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The researcher gratefully thanks the independent reviewers who took the time to review this manuscript.