All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Effect of Internet-based Cognitive-behavioral Approach on Sexual Intimacy of Women with Spouses having Spinal Cord Injuries: A Randomized Clinical Trial Study

Abstract

Introduction

Sexual intimacy is a fundamental component of marital relationships and may be adversely affected by chronic conditions, such as spinal cord injury in one or both partners. The present study aimed at determining the effect of internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy on the sexual intimacy of women with spouses having spinal cord injuries.

Materials and Methods

This research study was conducted as a parallel-randomized clinical trial (RCT) with a control group of women with spouses having spinal cord injuries. The participants in the study included 60 women (30 in the intervention group and 30 in the control group). Cognitive-behavioral intervention was performed on the intervention group in the form of eight 90-minute sessions. The control group received 4 sessions of sexual health education via pamphlets through WhatsApp. At baseline, 8 weeks after baseline, and at 12 weeks, both groups completed the Standard Sexual Intimacy Questionnaire. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 25, applying descriptive statistics, including t-tests and chi-square tests, as well as analytical statistics, such as repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc test.

Results

This study showed a statistically significant difference in sexual intimacy scores between the two groups (p=0.01). The internet-based CBT group displayed a higher mean score post-intervention (90.9±27.2) than the control group (71.8±22.8), and this trend persisted during the follow-up period (CBT: 77.9±22.5; control: 64.6±20.4).

Discussion

Internet-based CBT could improve the sexual intimacy of women with spouses having spinal cord injury.

Conclusion

The findings suggested that such interventions can be integrated into comprehensive care for women whose spouses have disabilities, delivered collaboratively by midwives and psychologists.

1. INTRODUCTION

Sexual intimacy is a complex and multidimensional aspect of relationships, involving emotional, physical, and psychological connections between partners during intimate moments. It requires trust, mutual understanding, and a strong bond, ultimately contributing to a more fulfilling relationship [1]. Intimacy involves exchanging personal details, emotions, and thoughts that create a sense of mutual understanding, appreciation, respect, and care for oneself and each other. In this context, the individual transforms into a collective “us”, and personal pleasure becomes a shared experience between the partners. The joy derived from personal pleasure expands to include the joy of pleasing one another [2]. Sexual intimacy is most important for sexual satisfaction [3]. On the other hand, lower satisfaction in relationships, particularly in terms of social and emotional intimacy, emotional expression, and self-disclosure, can significantly impact the quality of a sexual relationship [4]. In Iran, numerous reports indicate that many couples experience dissatisfaction with their sexual relationships [5]. Although the prevalence of sexual dysfunction is high among both men and women in Iran, precise statistics are lacking [6]. One study reported a prevalence rate of 31% among Iranian women [7]. In Turkey and Saudi Arabia, the rates of 45% and 60% have been reported, respectively [8, 9]. This issue is notably significant, as it is cited as a contributing factor in approximately 50% to 60% of divorces and around 40% of instances of sexual infidelity [10]. Sexual intimacy is influenced by a multitude of factors, including chronic diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and breast cancer, as well as psychological stressors, like anxiety, in couples. Additionally, physical disabilities, such as limb impairments, spinal cord injuries, and sensory deficits, including hearing loss, can significantly affect sexual relationships, impacting one or both partners. These factors can profoundly alter the dynamics of sexual interactions, underscoring the complex interplay among physical health, psychological well-being, and interpersonal relationships [4, 11-15]. The incidence of traumatic spinal cord injuries (TSCI) exhibits significant global variability, ranging from 3.6 to 195.4 cases per million people. In Iran, one study analyzed data from the National Trauma Registry between 1999 and 2004, revealing that traumatic spinal fractures (TSF) occurred in approximately 3.8% of trauma admissions, affecting 619 out of 16,321 cases [16, 17]. A qualitative study identified four key challenges faced by couples dealing with spinal cord injuries (SCI): difficulties in maintaining intimacy, navigating the complexities of care needs, redefining traditional masculine roles, and managing social isolation. These findings underscore the complex and multifaceted impact of SCI on interpersonal dynamics [18]. In another qualitative study on SCI patients and their partners, two major themes were identified: the changing definition of sex and emotions. Couples’ conversations about the changing definition of sex after SCI addressed the traditionally taboo topic of sexuality and highlighted the importance of open communication between partners, peers, and healthcare providers. Participants commonly expressed emotional concerns, such as fear of losing intimacy [19]. Hucker et al. reported that counseling and education through an online approach could improve sexual intimacy [20]. People with SCI and their wives are likely to experience anger, frustration, and low libido, which can affect their relationships. Creating new relationships and maintaining the existing relationships in life become more challenging for people with spinal cord injuries [21]. In Parker's study, people with SCI expressed that establishing intimate relationships with their wives has become challenging for them compared to before the injuries [22]. Rahimi et al. demonstrated that combining cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) significantly improved sexual satisfaction [23]. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is recognized as a prominent psychological intervention for enhancing sexual assertiveness and satisfaction. Rooted in the principle that thoughts and perceptions influence emotions and behaviors, CBT addresses sexual issues by targeting cognitive and behavioral patterns. This therapeutic approach assists individuals in overcoming sexual challenges by correcting misconceptions about sexuality, fostering sexual self-expression, promoting shared responsibility in intimate relationships, and enhancing problem-solving abilities [24]. This study was conducted with the aim of investigating the effect of internet-based CBT on sexual intimacy of women with spouses having SCI in accordance with the Spinal Cord Injuries Association of Yazd/Iran.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design and Setting

This educational study was a parallel (1:1) randomized clinical trial. The statistical population of this study consisted of married women with spouses having SCI in accordance with the Spinal Cord Injuries Association of Yazd/Iran.

2.2. Sampling and Sample Size

According to Babapour's study, the sample size was determined based on sexual intimacy, with 30 women allocated to each group. This calculation was derived by the G Power program, incorporating a standard deviation of 10.13, a mean score difference of 12.13, a power of 80%, a confidence interval of 95%, and a subject attrition rate of 15% [25].

2.3. Participants

The study contacted 78 couples who had registered their names with the Spinal Cord Injuries Association of Yazd, Iran, via telephone. Partners of men with spinal cord injuries (SCI) were invited to participate in the study, provided they met the inclusion criteria. In this study, 60 women were selected in accordance with the inclusion criteria of the study and the score obtained from the Standard Sexual Intimacy Questionnaire. The study duration, from initial design through data sampling and analysis, spanned nine months. This research study was conducted in 2022.

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for participation were as follows: women aged 18–45 years, married to a spouse with spinal cord injury (SCI), being the sole wife of their husband, having at least one year of shared married life, cohabiting in the same household, no intention of divorce, access to a smartphone and the internet, willingness to engage in online sessions, absence of self-reported drug addiction in both the wife and husband, no use of SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), not being pregnant, no concurrent participation in psychological or psychiatric interventions, and scoring moderate or low on the Standard Sexual Intimacy Questionnaire.

2.5. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were being absent in at least two online sessions and not filling the questionnaire completely.

2.6. Randomization Method

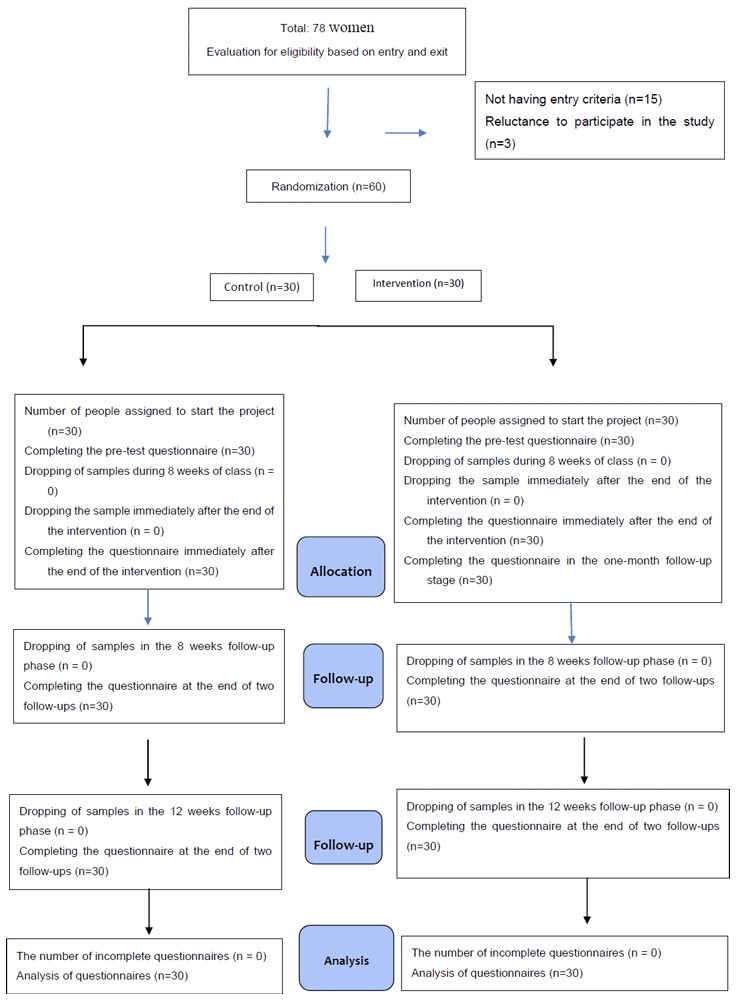

Sixty eligible women were randomly assigned to use the randomization site http://www.randomization.com by a biostatistician outside the research team. The randomization sequence was generated by an independent statistician using computer software, and assignments were placed in sealed, opaque envelopes to prevent bias. Blinding was not possible due to the obvious nature of the intervention. The Consort flowchart shows the steps of the study (Fig. 1).

CONSORT flowchart (study steps).

2.7. Intervention

Participants in both the intervention and control groups were provided with mobile phones equipped with WhatsApp. The intervention group received all messages via WhatsApp, while the CBT-based educational sessions were delivered through the Skyroom platform. To ensure uninterrupted participation, the researcher supplied a complimentary internet package, which remained valid for the entire 12-week study duration.

The CBT intervention was administered by the principal investigator, a master’s student in midwifery counseling with certified training in CBT and sexual counseling. All sessions were supervised by a clinical psychologist (third author); the details are summarized in Table 1 [26-28]. The control group received sexual health education via four WhatsApp messages, which included pamphlets covering topics, such as male/female anatomy, erogenous zones, and the sexual response cycle, in 4 sessions over one day a week. Individuals in the online group remained connected throughout the consultation. They were asked to submit their questions via the online chat function and subsequently received the necessary guidance from the researcher. After completion of the first session, members of the intervention group were asked at the beginning of each subsequent session to report any improvements and describe the changes they experienced in the specified areas based on the session content. Further, their possible questions were answered. Assignments for the subsequent stage were provided only if participants had completed the previous stage to an acceptable level, as determined by the researcher. If this criterion was not met, assignments for the next stage were withheld, and the previous stage’s assignments were reviewed instead. Each online group was reminded to complete the daily homework sent through SMS messages to the research participants. The consultant evaluated the assignments by reviewing participants’ summaries of their completed exercises. In the online group, this evaluation was conducted through related questions and images of the assignments submitted via each participant’s personal virtual page. The researcher also provided guidance on coordinating with the research team, including attending scheduled group chats, receiving homework reminders, and arranging private discussions outside the group chat when necessary. If a person was not present in the group, he was requested to receive the content of the said session through SMS. At the beginning of face-to-face counseling sessions, the topics of the previous session were briefly explained to all the people present in the class. In case of absence of people in the previous session, the topics were discussed in general in the class, and if more information was needed, their questions were answered individually at the end of the class session. It should also be noted that absenteeism from more than one session would result in the person's exclusion from the study. All people in the intervention and active control groups were present in the study until the end of the follow-up period, and none of the participants were excluded.

The primary outcome, i.e., mean sexual intimacy scores, was assessed at baseline, week 8, and week 12 (follow-up) in two groups.

| Sessions | Objective | The Content of the Session |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction to Sexual Health and Intimacy | Provide an overview of sexual health, intimacy, and the impact of SCI on sexual functioning. | - Anatomy and physiology of sexual response - Common sexual changes after SCI - Importance of open communication about sexuality Assignment: Reflect on your current understanding of sexual health and intimacy. Write down any questions or concerns you have about sexuality after SCI. Discuss with your partner what intimacy means to both of you and how you can support each other. |

| Understanding the Sexual Response Cycle | Educate participants about the stages of the sexual response cycle and how SCI may affect each stage. | - Phases of the sexual response cycle (desire, arousal, plateau, orgasm, resolution) - Adaptations and strategies to enhance each phase post-SCI Assignment: - Observe and journal about your own sexual response cycle over the next week. Note any changes or challenges you experience in each phase (desire, arousal, orgasm, resolution). - Research and write down one new way to enhance a specific phase of the sexual response cycle that you find challenging. |

| Cognitive Restructuring for Sexual Beliefs and Myths | Identify and challenge misconceptions or negative beliefs about sexuality after SCI. | - Common myths about sexuality and disability - Cognitive restructuring techniques to replace unhelpful thoughts with positive, realistic ones. Assignment: - Identify one myth or negative belief you hold about sexuality after SCI. Write it down and challenge it by listing evidence that contradicts it. - Replace the negative belief with a positive, realistic thought and practice repeating it daily. |

| Enhancing Communication Skills | Teach effective verbal and non-verbal communication skills to improve intimacy. | - Active listening and expressing needs/desires - Non-verbal cues and their role in intimacy - Practicing assertiveness in sexual communication Assignment: - Practice active listening with your partner (or a trusted friend) for 10 minutes. Focus on understanding their perspective without interrupting. - Write down three things you would like to communicate to your partner about your sexual needs or desires, and practice expressing them assertively. |

| The Role of Foreplay and Emotional Connection | Highlight the importance of foreplay and emotional bonding in sexual intimacy. | - Techniques for building emotional connection - Creative ways to incorporate foreplay into sexual activity - Addressing barriers to intimacy (e.g., fatigue, pain) Assignment: - Plan and engage in a non-sexual activity with your partner that fosters emotional connection (e.g., a shared hobby, a heartfelt conversation). - Experiment with one new form of foreplay and reflect on how it impacts your sense of intimacy |

| Managing Anxiety and Performance Pressure | Address anxiety and performance-related concerns that may hinder sexual satisfaction. | - Relaxation techniques (e.g., deep breathing, mindfulness) - Strategies to reduce performance pressure - Normalizing variability in sexual experiences Assignment: - Practice a relaxation technique (e.g., deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation) for 10 minutes daily. Reflect on how it affects your anxiety levels. - Write down three affirmations about your sexual self-worth and repeat them daily. |

| Problem-solving and Adapting Sexual Practices | Equip participants with problem-solving skills to adapt sexual practices post-SCI. | - Brainstorming solutions for common challenges (e.g., mobility limitations, bladder/bowel concerns). - Exploring alternative sexual activities and positions. - Incorporating assistive devices or aids if needed. Assignment: - Identify one sexual challenge you face (e.g., mobility limitations, bladder/bowel concerns) and brainstorm three possible solutions. Discuss these with your partner or therapist. - Experiment with one new sexual position or activity that accommodates your physical abilities and reflect on the experience. |

| Maintaining Intimacy and Long-term Sexual Well-being | Provide tools for sustaining intimacy and sexual satisfaction over time. | - Strategies for maintaining emotional and physical connection - Setting realistic expectations for sexual intimacy - Resources for ongoing support (e.g., sexual health professionals) Assignment: - Create a “sexual well-being plan” that includes regular activities to maintain emotional and physical intimacy (e.g., date nights, communication check-ins). - Write a letter to yourself about your progress and goals for continued sexual health and intimacy. |

2.8. Data Collection Instruments and Study Outcomes

2.8.1. Demographic Characteristics Questionnaire

This included information on age, spouse's age, wife's level of education, spouse's education level, history of pregnancy, duration of husband's disability, type of marriage, bedroom condition, type of husband's spinal cord injury, length of marriage, physical problem in women, and number of children.

2.8.2. Standard Sexual Intimacy Questionnaire

The standard sexual intimacy questionnaire was a 30-item scale prepared by Botlani [29] and Shahsiah [29] using Bagarozzi's marital intimacy questionnaire. In this scale, each item has a range of 4 options (always, sometimes, rarely, and never), scored from 1 to 4, with the maximum score being 120 and the minimum score being 30. A score between 30 and 50 indicates low sexual intimacy, a score between 51 and 100 indicates moderate sexual intimacy, and a score above 101 indicates high sexual intimacy. This scale can be used to separate diagnostic groups, i.e., those with the problem of lack of sexual intimacy and those without this problem. Validity and reliability of the inventory were confirmed in Botlani's study with a Cronbach's α coefficient of 81% and a reliability index of 78%.

2.9. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present and describe information, draw graphs and tables, and calculate percentages, means, and standard deviations, while inferential statistics were used to analyze the difference in mean scores. Independent t-tests and chi-square tests were used to test the demographic variables, and a repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare the mean sexual intimacy at baseline and at the 8 and 12 weeks in each of the intervention and control groups. The Tukey test was employed to compare the means of the desired quantitative traits between the intervention and control groups at baseline and at 8 and 12 weeks. In the data analysis, the confidence level of the tests was set at 95% (p<0.05).

3. RESULTS

The data of 30 women in the intervention group and 30 women in the control group were subjected to statistical analysis. There was no attrition in both the groups.

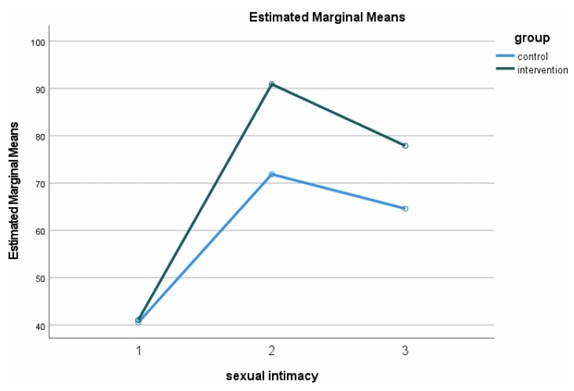

The comparison of demographic characteristics between the two groups is shown in Table 2. Based on the information provided, the study demonstrated a significant improvement in sexual intimacy among women whose spouses had spinal cord injuries (SCI). The intervention group receiving internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) exhibited a marked increase in scores immediately post-intervention and maintained better outcomes compared to the control group at follow-up. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference in sexual intimacy scores between the two groups (p=0. 01). The CBT group displayed a higher mean score post-intervention (90.9±27.2) than the control group (71.8±22.8), and this trend persisted during the follow-up period (CBT: 77.9±22.5; control: 64.6±20.4). These findings confirmed the superior efficacy of CBT in enhancing sexual intimacy compared to traditional educational methods (Table 3).

| Characteristics | Active Control Group | Intervention Group | - | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | p-value | |||

| Woman’s age | 31.5±6.1 | 31±7.5 | *0.766 | ||

| Spouse’s age | 34.2±6.9 | 34.1±7.2 | *0.942 | ||

| Duration of marriage | 4.8±2.7 | 4.2±2.2 | *0.310 | ||

| The duration of the man’s spinal problem | 3±1.7 | 3.6±1.9 | *0.164 | ||

| Number of children | 1.4±0.8 | 1.3±0.7 | *0.535 | ||

| Type of spinal cord problem | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | - |

| Complete | 4 | 13.3 | 3 | 10 | - |

| Incomplete | 26 | 86.7 | 27 | 90 | **0.688 |

| Total | 30 | 100 | 30 | 100 | - |

Note: *Independent samples t-test. **Chi-square test.

| Group | Before Intervention | 8th Week After Baseline | 12th Week After Baseline | CI | *p-value within Groups | *p-value between Groups | Partial Eta Squared | P **value (1,2) | **p-value (1,3) | **p-value (2,3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active control | 40.5±5.9 | 71.8±22.8 | 64.6±20.4 | 52.95- 65.04 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Intervention | 41.0±4.7 | 90.9±27.2 | 77.9±22.5 | 63.90-69.95 | 0.001 |

Note: * Repeated measurement ANOVA test. ** Tukey test. 1: before intervention. 2: 8 weeks. 3: 12 weeks.

The graph of sexual intimacy in the intervention and control groups. 1: before intervention. 2: 8 weeks. 3: 12 weeks.

4. DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of online cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in enhancing sexual intimacy among women with spouses experiencing spinal cord injury (SCI). The findings revealed that while sexual intimacy improved in both the intervention and control groups, the rate of improvement was significantly greater in the CBT intervention group compared to the pamphlet-based education group. There is no doubt that education can change awareness and behavior. However, the extent of this change, its persistence, and the depth of its effect on an individual's cognition and behavior can undoubtedly vary across different methods. In the present study, the level of sexual intimacy showed a marked increase in the counseling group compared to the control group, and the difference between the groups was statistically significant. Consequently, the researchers have employed various educational and counseling methods in different studies to investigate the impact of each approach on enhancing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Although the pamphlet increased sexual intimacy, the magnitude of this increase was significantly smaller than that observed in the intervention group.

These results have been found to align with previous studies by Hucker and McCabe, which explored the efficacy of an online mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) program designed to address female sexual difficulties and its effects on relationship functioning. The study found that the intervention significantly improved key aspects of sexual health, such as desire, arousal, and satisfaction, while also enhancing emotional intimacy and communication within the relationships [20]. Also, Bokaie [30] demonstrated online CBT to not only address women's sexual problems, but also enhance their sexual intimacy. Similarly, Farajkhoda's research found that online counseling was more effective than traditional face-to-face training in improving sexual health outcomes [31]. The CBT intervention employed in this study focused on restructuring irrational sexual thoughts about oneself, one’s spouse, and the relationship. Techniques, such as positive self-talk, focused attention, and self-expression, were utilized to foster cognitive and emotional changes. These strategies collectively contributed to improved sexual intimacy between the couples. Furthermore, the findings highlighted that CBT techniques enhance sexual awareness, develop sexual skills, and utilize imagination and systemic insight to address underlying causes of sexual challenges. Behavioral interventions, such as reducing performance anxiety and increasing emotional connection, were also effective in positively influencing women's sexual desire and intimacy [23].

It is noteworthy that in the control group, which received education via pamphlets, a slight increase in women's sexual intimacy was observed. It seems that the issue of sexual education is so significant for these women that even simpler methods, such as providing pamphlets, can be somewhat effective. This highlights the urgent need for these women to receive information and education related to sexual health, which can be partially addressed even through low-cost methods.

A limitation of this study was the occasional disconnection during online meetings due to weak internet infrastructure; this was mitigated as much as possible by addressing participants’ questions individually.

Moreover, while the follow-up data demonstrated sustained improvements in sexual intimacy, the slight decline in scores over time suggests the necessity of booster sessions to maintain therapeutic gains. Longitudinal studies with extended follow-up periods could provide more insights into the long-term effectiveness and scalability of such interventions.

CONCLUSION

The study's implications extend beyond the specific context of SCI, offering valuable lessons for addressing sexual health challenges in other populations with chronic health conditions. The integration of CBT into routine care practices by healthcare providers, such as midwives and psychologists, could significantly enhance the quality of life for affected couples.

This study involves several limitations that need consideration. The findings may not be generalizable due to the relatively small sample size and its recruitment from a single center in Iran. The assessment of the long-term effects has been constrained by the short one-month follow-up period. The lack of participant blinding and the use of self-reported measures for the primary outcome may have introduced bias. Furthermore, the study faced technical challenges, as weak internet infrastructure occasionally disrupted the online intervention delivery.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the study as follows: M.B. and M.M.: Conception and design, provision of study materials to patients, data collection and assembly, data analysis and interpretation, article writing, reviewing, and editing; F.A.: Conception and design, reviewing, and editing. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| SCI | = Spinal cord injury |

| CBT | = Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Research Deputy of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.SSU.REC.1400.193). Also, the study is registered with Iran's clinical trial registration code: IRCT20220227054139N1 (www.irct.ir).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee, and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The datasets used and analyzed during the present study will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper was extracted from a Master’s thesis in midwifery counseling. The authors would like to express their appreciation to all participants and the personnel of the Spinal Cord Injury Association of Yazd for their cooperation in conducting this research.