All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

A Systematic Literature Review of Husband’s Support for the Incidence of Postpartum Depression in Indonesia

Abstract

Purpose

Postpartum Depression (PPD) is a common mental health problem among mothers in Indonesia and negatively impacts families. A key factor contributing to PPD is a lack of physical, emotional, and psychological support from husbands. This support is crucial in preventing the condition. This study conducted a systematic review to examine husbands' support by region and examine the role of culture in the incidence of PPD in Indonesia.

Methods

This study used a systematic review methodology to collect and analyze relevant literature from PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect databases. The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD420250655837).

Results

Of the 1,421 articles screened, only 4 met the criteria for final review. The findings showed that husbands' support was negatively correlated with postpartum depression. Low levels of husbands' support were associated with poor marital quality, limited awareness, and sociocultural norms.

Discussion

The key role of husbands in postpartum women's mental health is crucial. This support can include living with their wives, postpartum support, attention, and care.

Conclusion

The high prevalence of postpartum depression among mothers in Indonesia is influenced by a lack of physical, psychological, and emotional support from their husbands. This review recommends the enhancement of campaigns such as “Suami SIAGA” (Alert Husband), “Ayah ASI” (Breastfeeding Father), and the implementation of postpartum depression screening programs to increase husbands' knowledge and awareness, as well as encourage their active role in preventing postpartum depression.

1. INTRODUCTION

Postpartum Depression (PPD) is a serious mental health disorder. This disorder appears after childbirth with symptoms such as poor mood, poor sleep quality, loss of energy, erratic mood, tendency to feel upset, anxiety, and suicidal ideation [1]. Some studies show PPD can occur within 4 weeks after childbirth, 3 months, 6 months, and even up to 12 months after delivery [2]. Spencer in Widyastuti (2023) states that some women experience postpartum stress due to feelings of failure to become a mother in adjusting to conditions with her new role. Unlike the temporary baby blues, Postpartum Depression (PPD) can last a long time and interfere with daily productivity. However, low awareness and social stigma often prevent early diagnosis.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2025, 1 in 5 mothers in developing countries experience postpartum depression. This is 20% higher than the incidence in developed countries. This condition poses life-threatening risks (suicide or psychosis) and disrupts child development. Indonesia is one of the developing countries with a high prevalence of PPD. Based on the Indonesian Health Survey (SKI) in 2023, it is known that one of the danger signs of postpartum is depression; the average sign of depression in women aged 10-54 years in provinces in Indonesia is 15.5% [3]. The prenatal and postnatal periods are among the mental health priorities in Indonesia, with a prevalence rate of 22.2%. This figure is associated with the critical window of the first 1000 days of life, which is identified as one of the four high-risk groups for mental health disorders in Indonesia [4].

Indonesia is one of the countries where most people adhere to a patriarchal system in social culture. This condition causes the role of fathers in the household to be less than optimal. The patriarchal system places women in a lower position than men, both in the public and domestic spheres. In a patriarchal culture, wives have a domestic role that includes various household tasks such as cooking, washing clothes and tableware, cleaning the house, and caring for children. Meanwhile, husbands are tasked with being the breadwinner, protector, and leader of the family, and are not required to be involved or help with housework. This view creates a gender perception in society that considers men superior to women [5].

Married couples in Indonesia generally have interactions influenced by the values and norms that apply in the family's social structure. Husbands are often considered the head of the household and need to carry out duties in serving their wives, such as helping their wives during labor and doing household chores, which is one of the values and norms in the family social structure. This shows that the husband's role in accompanying his wife is essential, especially during pregnancy and childbirth [6]. Research by Alonazi & Saulat (2022) shows that PDD has an association with maternal social support factors. Women who didn't receive help from their husbands and had conflicts with their husbands were statistically significantly associated with PPD [7-9].

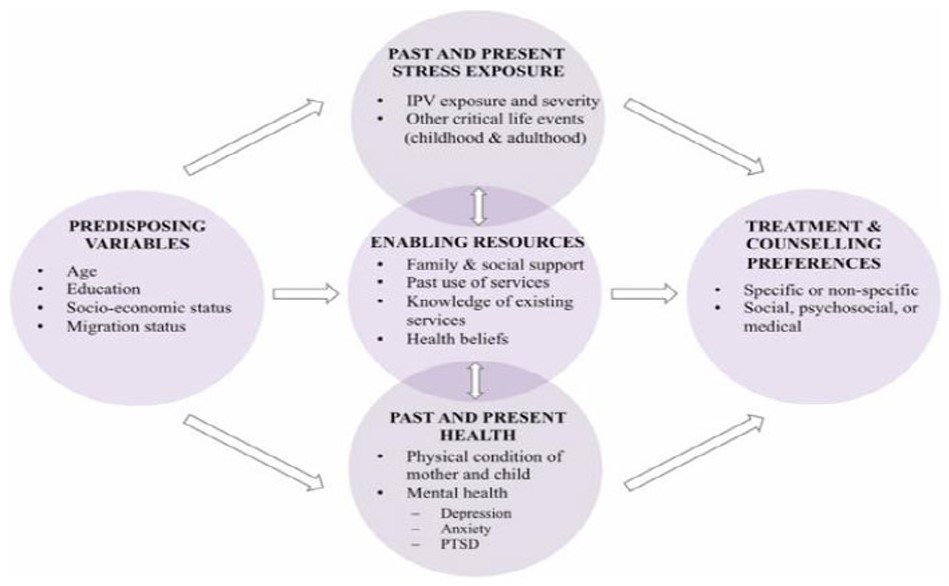

Mental disorders in mothers can undoubtedly harm themselves and affect the development of the baby. Mothers with PPD tend to experience rapid mood swings, cognitive impairment, and the desire to harm themselves and their babies. PPD will affect the mother's parenting of the infant, where a lack of responsiveness, sensitivity, and mother-child bonding will lead to significant behavioral problems in the child in the long term [10, 11]. The following is the theoretical framework of the INVITE (Intimate partner Violence care and Treatment preferences in postpartum women) study, adapted from the Andersen (1995) and Liang et al. (2005) models [12, 13].

Therefore, given the high prevalence of PPD in Indonesia and the potential role of husbands as a significant protective factor, there is an urgent need for research that can bridge the theoretical and empirical gaps (Fig. 1). This gap is mainly related to the lack of a comprehensive analysis of the interaction between husband support, patriarchal cultural norms, and urban-rural sociocultural differences in influencing maternal depression levels of postpartum depression in Indonesia [14].

2. METHODS

This Systematic Literature Review is written per the PRISMA (Preferencing Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. A narrative synthesis approach following Popay et al. (2006) was used to summarize and interpret findings across heterogeneous study designs [15]. The stages of the Systematic Literature Review are as follows:

2.1. Systematic Review Registration

Registration of this systematic review research has been carried out at PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) with ID Number CRD420250655837.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are discussed in the following table.

2.3. Data Sources and Searching Strategy

Data collection was conducted 10 years from April 2016 to March 2025 on four databases: Scopus, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. The keywords were combined based on Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Postpartum Depression, Husband Support or Husband Involvement, and Indonesia. Language was explicitly selected in English, and the journal search year was not restricted in the initial search. A full-text review was conducted and tailored to the research objectives. The query used in searching articles in the journal database was “Postpartum depression” AND “husband support” OR “husband involvement” AND “Indonesia.” The number of articles in each database search included the following (Table 2).

| Component | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population Postpartum mother | Postpartum mother in Indonesia | Non-postpartum (maternal, prenatal, adolescent, etc.) |

| Intervention Availability of husband support | Evaluation of husband support (emotional, physical, physiological) | No mention of husband's support |

| Comparison Lack of husband support or minimal support | comparing between mothers with adequate husband support and minimal support | No mention of husband’s support |

| Outcome Postpartum depression | depression in postpartum | does not measure postpartum depression specifically |

| Component | Query | Articles Obtained |

|---|---|---|

| Scopushttps://scopus.com | “Postpartum depression” AND “husband support” OR “husband involvement” AND “Indonesia” | 122 |

| Pubmed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ | 71 | |

| ScienceDirect https://www-sciencedirect-com | 799 | |

| Google Scholar https://www.https://scholar.google.com/ | 429 | |

| Total | 1421 | |

2.4. Software Used

Research articles were selected using the Rayyan.ai software and Reference Manager (Mendeley).

2.5. Selection Process

A thorough screening procedure must be followed to evaluate the gathered literature's relevance, reliability, and methodological rigor. Three reviewers (NR, SWL, and SHHK) independently reviewed studies, titles, abstracts, and full texts, selecting articles according to predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Screening and selection of duplicate articles was performed using the Rayyan.ai software. Reviewers extracted data based on author, publisher, publication year, region, respondents' mean age, and depression level.

2.6. Quality Assessment

A quality assessment was conducted using eight criteria based on the JBI’s Critical Appraisal Tools to assess the quality of articles to be discussed in the literature review. The following table presents the JBI scores for each research article. The JBI tool includes 10 items scored 0 or 1. If an item was not applicable (NA) for the study, it was not scored. The total score was calculated as the sum of obtained points divided by the maximum possible score after excluding NA items. Scores ranged from 0 to 1 and were classified as very weak (0-0.20), weak (0.21-0.40), moderate (0.41-0.60), strong (0.61-0.80), and very strong (0.81-1)—assessment conducted by NR and SHHK.

The quality assessment results presented in Table 3 indicate that all four articles had a strong quality assessment. This indicates that the articles used in the literature review have a relatively low risk of bias.

| No | Research Article | JBI Score | Classified |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Postpartum depression in young mothers in urban and rural Indonesia [16] | 0.75 | Strong |

| 2. | Differences in postpartum maternal depression levels based on characteristics of maternal age and husband support [17] | 0.75 | Strong |

| 3. | Associations between spousal relationship, husband involvement, and postpartum depression among postpartum mothers in West java, Indonesia [18] | 0.75 | Strong |

| 4. | Trends and risk factors of postpartum depressive symptoms in Indonesian women [19] | 0.67 | Strong |

3. RESULTS

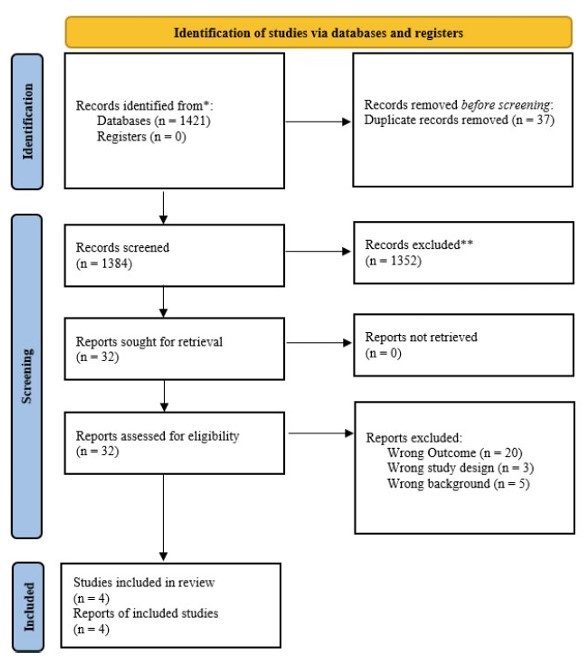

After initial screening, 1421 articles were obtained from four data sources: Scopus, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and PubMed. The next step is to remove duplicates, bringing the total to 1384. At the stage of further screening related to the title and abstract, and after reading the full text, four articles were included in the systematic review. Detailed information is outlined in Fig. (2).

PRISMA flow.

Table 4 describes the characteristics of the selected studies, which include author, title, location, study design, sample, mother's age, and mother's education.

| Author | Title | Location | Design Study | Sample | Mother’s Ages (Years) | Mother’s Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alifa Syamanta Putri (2023) [16] | Postpartum Depression in Young Mothers in Urban and Rural Indonesia | Indonesia (RISKESDAS data) | Cross Sectional | 1285 sample | 15 - 24 | Average education: 1. High school or above: 46,4% 2. Junior high school or less: 53,6% |

| Tisandra Safira Handini (2021) [17] | Differences in Postpartum Maternal Depression Level Based on Characteristics of Maternal Age and Husband Support | Surabaya | Cross sectional | 70 sample | 1. Ages <20 2. 20-25 3. 26-30 4. 31-35 5. >35 |

Not Reported |

| Elit Pebryatie (2022) [18] | Associations Between Spousal Relationship, Husband Involvement, and Postpartum Depression among Postpartum Mothers in West Java, Indonesia | West Java, Indonesia | Cross sectional | 336 sample | Lowest age 18 years, mean age 28 years | 1. Elementary School = 50 (14.9%) 2. Junior & Senior High School = 236 (70.2%) 3. Diploma & undergraduate = 50 (14.9%) |

| Astri Mutiar (2025) [19] | Trends and Risk Factors of Postpartum Depressive Symptoms in Indonesian Women | West Java, Indonesia | Prospective study | 124 sample | 18 years or older | 1. < 9 years = 52 (41,9%) 2. > 9 years = 72 (58,1%) |

The characteristics of the articles to be analyzed in the systematic review are in Table 4. The year of publication of the articles ranged from 2021 to 2025 and came from all or part of Indonesia. Three articles used cross-sectional research, and one used a prospective study, with sample sizes of 1,285 women (A), 70 women (B), 336 women (C), and 124 women (D). The ages of respondents in the four articles ranged from 15 to >35 years. Respondents also had varying levels of education, ranging from elementary school to university degrees.

Table 5 shows the differences in methods and results in the 4 selected journals. The division includes the author, data analyst, variables, instrument, level of PPD, level of husband support, mother’s education, and conclusion.

| Author | Data Analyst | Variables | Instrument | Score Instrument | Prevalence of PPD | Prevalence of Husband Support | The Relationship Between PPD and Husband Support | Effect Size and CI | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alifa Syamanta Putri (2023) | Multivariate | Dependent Variable: Postpartum depression Independent Variables: a. Demographic characteristics (family size, number of children, age below 5 years, education level, employment status, husband's education, husband's employment status, wealth index, living with husband, depression status) b. Reproductive health factors (age at first pregnancy, total parity, unwanted pregnancy, gestational age at birth, chronic energy deficiency, |

Postpartum depression: Mini International Neuro Interview (MINI) based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) Husband Support: Not applicable |

MINI: 10 questions answer “yes” = 1, “no”=0 Respondents were categorized as having depression if they answered minimal 2 “yes” to questions 1-3, and minimal 2 “yes” to questions 4-10. |

PPD in urban areas: a. Depression: 5,7% b. Not depressed: 94,3% PPD rural areas: a. Depression: 2,9% b. Not depressed: 97,1% Average PPD: a. Depressed: 4% b. Not depressed: 96% |

Urban area: a. Living with husband: 66,9% b. Not living with husband: 33,1% Rural areas: a. Living with husband: 61,5% b. Not living with husband: 38,5% Average: a. Living with husband: 63,6% b. Not living with husband: 36,4% |

Bivariate analysis of PPD with husband support Urban areas: P-value 0.183 Rural areas: P-value: 0.880 Mean: P-value: 0.567 In multivariate analysis, the variable of living with husband in urban areas had a p-value of 0.019, and in rural areas a p-value of 0.427, with a mean p-value of 0.255. |

P-value: 0.019 OR: 3.82 95% CI: 1.24 - 11.76 |

Living with the husband in urban families had a higher significance on the incidence of postpartum depression compared to other variables. |

| pregnancy complications, delivery complications, postpartum complications, and contraceptive use) | |||||||||

| Tisandra Safira Handini (2021) | Bivariate | Dependent Variable: Postpartum depression level Independent Variables: 1. Maternal age 2. Husband support |

Postpartum depression: Questionnaire Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Husband Support: Questionnaires were adopted and modified from Asmayanti’s (2017) research |

Not Applicable | 1. PPD distribution: a. Not at risk: 60% b. Low risk: 15.7% c. High risk: 24.3% |

Husband's support distribution: a. Low: 2.9% b. Medium: 37.1% c. High: 60% |

Differences in postpartum depression mothers rates based on husband support: a. Low support: 11.8% at high risk of depression b. Moderate support: 82.4% at high risk of depression. c. High support: 88.1% not at risk of depression. P-value: 0.000 |

P-value: 0.000 OR: Not reported CI: Not reported |

There is a significant difference in the level of depression of postpartum mothers and their husbands’ support. Mothers have a high risk of depression when they only get moderate support from their husbands. |

| Elit Pebryatie (2022) | Multivariate | Dependent Variable: Postpartum Depression Symptoms Independent Variables: 1. Spousal relationship (quality of partner relationship) 2.Husband involvement: involvement in maternal care, instrumental support (practical help such as financial and domestic), emotional support (affection and motivation), informational support (providing health information). 3. Maternal healthy behavior |

Postpartum depression: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Husband Support: Questionnaire Survey: Quality of Marriage Index (QMI) dan |

EPDS: 10 questions were used on a 4 point likert scale. QMI: The first 5 items utilized a 7-point response format, whereas the final item applied a 10-point scale, anchored at 1 (unhappy) and 10 (perfectly happy). |

Not Reported | Not Reported | Effect of husband involvement on postpartum depression (PPD) symptoms: γ = -0.21, P < 0.001: the higher the husband's involvement, the lower the maternal PPD symptoms. |

P-value: <0.001 Regression coefficient: -0.21 CI: not applicable |

Husband's support and involvement were statistically significant in reducing postpartum depression symptoms. |

| Astri Mutiar (2025) | Multivariate | Dependent Variable: Postpartum Depression Symptoms Independent Variables: 1. Maternal age 2. Education mother 3. Psychosocial Risk Factor (marital relationship satisfaction, dan postpartum key helper, include mother, in law and husband) |

Postpartum Depression: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Husband Support: Demographic and Psychosocial Risk Factor Questionnaire |

EPDS: Score 0-30; ≥10 indicates risk of postpartum depression, which consists of 10 questions on a scale of 0-3 with a sensitivity of 91.7% a specificity of 76.9% Husband Support: Marital satisfaction categories: General/Satisfied/Very Satisfied; Primary companion: Mother/In-law/Husband |

On day 7 postpartum, the prevalence of postpartum depression (PPD) was 33.9%. On day 40 postpartum, the prevalence of PPD decreased to 30.6%. | Not Reported | There is a positive relationship between marital relationship satisfaction (which involves husband's support) and a reduced risk of PPD, without specific prevalence figures or statistics related to husband's support. | Coeff linear regression: husband support -0.75 CI: 2,08-(-0.58) |

Women with low support from their husbands have a higher risk of postpartum depression symptoms. |

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Role of Husband Support

This study shows how husband support, especially when the husband lives with his wife, is vital for protecting the mental health of mothers in the postpartum period. The presence of a husband not only provides emotional stability but also contributes to reducing psychological distress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms experienced by new mothers. Husband involvement, especially the quality of the marital relationship during pregnancy and after childbirth, significantly reduces the risk of postpartum depression. A history of depression during pregnancy was the strongest predictor of postpartum depression. However, factors related to the husband, such as effective communication, marital satisfaction, and consistent emotional support, also played a critical role. Couples with strong communication skills reported lower depression rates, highlighting the importance of a supportive relationship [20].

High levels of husband support, including constant presence, attentiveness, and responsiveness, reduced the likelihood of postpartum depression [21]. Conversely, insufficient support increased the risk, with mothers lacking husband support being 6.013 times more likely to develop postpartum depression. Creating a positive and secure environment was shown to help prevent depressive symptoms [8]. Low husband support led to significant drops in estrogen, progesterone, and cortisol levels within 48 hours after childbirth, increasing susceptibility to depression [22].

4.2. Husband Support: Rural vs Urban

A comparison of the impact of husbands' support in urban and rural areas found that urban mothers who lived with their husbands had a higher risk of postpartum depression [23]. Multivariate analysis confirmed that women who did not live with their husbands were significantly more likely to experience postpartum depression. These results are consistent with cohabitation and husband’s support as key protective factors against depression in Brazilian mothers with children under two years of age. Urban husbands tend to work full-time, resulting in less time spent with their wives.

In contrast, rural mothers showed lower rates of postpartum depression due to strong community ties and social support systems, which compensated for the lack of husbands' involvement [24, 25]. This suggests that while husbands' support is crucial, its absence can be offset by strong social networks within a close-knit community to reduce postpartum depression. This difference highlights a shift in expectations and support structures: in urban environments focused on the nuclear family, husbands become the main and almost sole source of emotional and practical support. In contrast, in rural environments, support is communal in nature, where the responsibility of caring for mothers and babies is distributed among extended families and neighbors, making the husband's role part of a broader social ecosystem, rather than the sole pillar.

4.3. Role of Social Support

Women who received primary support from their own mothers exhibited significantly fewer depressive symptoms than those whose primary source of support was their husbands. During the breastfeeding period, 90% of mothers reported needing support from their husbands. In Indonesia, it is also common for postpartum mothers to live with extended family to receive help with housekeeping, self-care, and childcare. This family support can create comfort, thereby reducing the risk of postpartum depression. Thus, the role of husbands and family is proven to be very important in maintaining mothers' mental health [26, 27].

According to Stress-Buffering Models, other support (friends and family) may mitigate depression caused by a lack of husband support. However, husbands' support plays a unique and fundamental role that other forms of social support cannot fully replace. It provides aspects not found in friends, family, or the community, including emotional intimacy, co-parenting (shared responsibility for caring for the baby), and marital relationship quality [28].

4.4. The Impact of Patriarchal Culture

Four key aspects of husband involvement: instrumental, emotional, and informational support, as well as participation in maternal care [29]. Instrumental support included practical help such as household chores and childcare, while emotional support involved empathy and encouragement. Informational support covered health education, and maternal care participation included attending antenatal visits and assisting with breastfeeding. This comprehensive approach helped reduce postpartum depression by lowering stress and improving emotional stability [11, 30]. According to Cohen & Wills’ theory, such involvement acts as a buffer against stress by enhancing the mother’s ability to cope with psychological and physical changes after childbirth [31-33].

However, patriarchal cultural norms in Indonesia often limit husband support, placing the burden of childcare entirely on mothers and increasing their emotional strain [34]. Patriarchy creates conditions that increase mothers' vulnerability through pressure to be the 'perfect mother', which leads to feelings of failure when they encounter difficulties. The pressure to fulfill the demands of being a ‘perfect mother’ is related to the theory of Cultural Expectations of Motherhood. This theory explains that when difficult postpartum experiences conflict with highly idealized cultural narratives, mothers experience intense cognitive dissonance, which triggers deep feelings of guilt and inadequacy.

The lack of practical and emotional support from husbands, whose roles are often limited to being breadwinners, leaves mothers feeling alone and overwhelmed. In addition, the intense stigma surrounding mental health considers complaints to be shameful or ungrateful, so mothers are reluctant to seek help and bottle up their feelings. The loss of self-identity that comes with being seen only as 'the mother of her children' also contributes to this. Therefore, patriarchy acts as a catalyst that exacerbates risk factors by creating an environment full of pressure, minimal support, and stigma, which hinders early treatment [26, 35, 36]. Thus, patriarchal culture not only removes the mother's primary support system, her partner, but also actively erects barriers that make it difficult for her to seek help from other sources. This combination of emotional overload and isolation is what leads to the development of postpartum depression.

4.5. Mitigation of Postpartum Depression

Husbands play the role of primary caregivers and companions for postpartum mothers. Couples whose husbands serve as primary caregivers during the postpartum period are less likely to experience depressive symptoms. Conversely, those without such support are more likely to experience it. This highlights the protective role of partner involvement in mitigating postpartum depression. Husbands are expected not only to be present but also to actively participate in supporting the mothers.

Physical, emotional, and psychological support from husbands plays a crucial role in reducing the risk of postpartum depression in mothers. Physical support provided by a husband, such as helping with household chores and caring for the baby, can ease the mother's burden, reducing fatigue and stress that can trigger depression. Furthermore, emotional support, manifested through the husband's active presence, attention, and understanding, also provides a sense of security and comfort to the mother, thereby strengthening emotional stability and reducing feelings of loneliness [28, 30]. Psychological support, including motivational encouragement, open communication, and increased maternal self-confidence, helps address the mental stress that occurs during the postpartum period. The combination of these three forms of support forms an effective support system in reducing stress and improving the psychological well-being of postpartum mothers, thereby significantly reducing the risk of postpartum depression [31, 33].

4.6. Implication for Intervention and Policy

In Indonesia, there are several programmes with significant potential, such as 'Suami SIAGA' or ‘Husband Alert’ and 'Ayah ASI' or ‘Breastfeeding Father’, but their implementation has not been optimal or integrated. 'Suami SIAGA' ('Suami Siap Antar Jaga') is a government programme that educates husbands about the danger signs of pregnancy and childbirth and their role in postnatal care through counselling and motherhood classes. Meanwhile, 'Ayah ASI' is a community initiative that prioritises practical training for husbands in supporting breastfeeding and the psychological well-being of mothers. Comprehensive synergy between these two programmes is essential. By combining the medical parts of Suami SIAGA and the emotional support of Ayah ASI, husbands will become more informed and active supporters. This practical and emotional support has been proven to reduce stress, strengthen the parent-child bond, and ultimately lower the risk of postpartum depression in mothers [34, 35].

5. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATION

This study has the advantage of exploring the role of husband support in PPD in depth within the context of Indonesian culture. These findings are expected to reference countries with cultures or ideologies similar to Indonesia, such as India, South Korea, Sri Lanka, and Japan, particularly regarding husband support [36, 37]. However, this study also has several limitations. Quantitative literature sources on PPD in Indonesia are still limited, making it challenging to conduct in-depth analysis and comparison of research. Restricted access to databases affects the completeness of reference sources. In addition, using Rayyan AI in the article extraction process does not allow researchers to make detailed exclusion reasons; researchers only rely on recommendations from the system. Nevertheless, the findings in this study can still contribute to understanding the issue of husband support for PPD in Indonesia.

CONCLUSION

Husband support, whether physical, emotional, or psychological, plays a crucial role in reducing the risk of Postpartum Depression (PPD) in Indonesian mothers. Women with less support are more likely to experience PPD than those with more support during and after pregnancy. Social support from relatives and family can reduce PPD, but cannot fully replace the role of a husband because it does not provide the benefits a partner offers. The strong patriarchal culture in Indonesia plays a role, as mothers sometimes feel isolated and stressed. Educational programs and campaigns for “Suami SIAGA” and “Ayah ASI” must be optimized by involving community leaders and health workers. The government is expected to implement maternity leave policies for mothers and paternity leave for husbands to increase their involvement in childcare. Further research is needed to explore the issue of husband support in reducing PPD.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: D.R., R.W.B., S.H.H.K., and S.W.L.: Responsible for writing, reviewing, and editing the manuscript, while nr prepared the original draft. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| PPD | = Postpartum Depression |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

| MeSH | = Medical Subject Headings |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the Varians Statistik Kesehatan and Kaukus Masyarakat Peduli Kesehatan Jiwa for providing the boot camp and mentoring to improve the manuscript writing.