All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Amount of Informal Payments among Patients Referring to Public Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study from the Capital of Iran

Abstract

Introduction

Informal payments are considered a systemic form of corruption that is a major obstacle to reforming healthcare systems in many contexts and has adverse effects on the functioning of these systems. This study aimed to determine the extent of informal payments in selected governmental hospitals in Tehran, the capital of Iran, in 2024.

Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study was conducted on 336 patients discharged from selected hospitals. Data were collected using a standard questionnaire measuring informal payments that had been used in previous studies in Iran. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 23 software. For this purpose, descriptive statistics including frequency and percentage, Mann-Whitney, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used.

Results

The results showed that 19.94% (67) of the participants made informal payments in cash or as gifts to healthcare providers. The total amount of informal cash payments made was US$1235.75 (840 million Iranian Rials). There was a statistically significant relationship between the amount of informal payments to physicians and the length of hospital stay (p = 0.021)

Discussion

The persistence of informal payments indicates systemic weaknesses in financial transparency, monitoring, and income regulation mechanisms within the public healthcare sector. These findings highlight the need for structural reforms to address the economic and ethical drivers of informal payments. By emphasizing equitable compensation, patient education, and strict oversight, healthcare policymakers can reduce financial inequities and enhance trust between patients and providers.

Conclusion

The findings of this study show the occurrence of informal payments in the hospitals studied. Given the harmful effects of these payments, it is recommended to educate patients and hospital staff, adjust staff income levels in line with inflation, improve the quality of care, and strengthen monitoring mechanisms.

1. INTRODUCTION

Health care systems are not only responsible for promoting the health of individuals in society, but also for protecting them from the financial costs of adverse health outcomes by reducing the burden of out-of-pocket payments for health care. Subsidy programs and the expansion of prepayment programs are at the center of these efforts [1]. Out-of-pocket payments are considered the worst and most inequitable form of healthcare financing [2]. From both a risk protection and equity perspective, this financing method has many adverse effects and places individuals at the highest risk of financial distress [2]. One of the phenomena that has exacerbated the problems related to this financing method in recent years is informal payments [3,4]. Economically, informal payments are considered a form of direct out-of-pocket financing, as they have similar effects on demand and financial burden [5]. Informal payments are a major source of health care financing in many developing countries and a significant obstacle to health system reform [6].

Informal payments include illegal payments made to healthcare providers in exchange for services that should be provided free of charge to patients [7,8]. These payments can take many forms, including cash payments, gifts, or goods and services [4,9]. Under-the-table payments, black money, gray money, and corrupt payments are other terms used for informal payments [2]. Despite the high relevance of this issue, there is a lack of comprehensive, up-to-date data on the magnitude of informal payments in Iran, particularly in Tehran, which limits the ability to evaluate the effectiveness of policy interventions.

Informal payments for healthcare can be seen as a strategy to cope with resource shortages and poor performance on both the supply and demand sides [5]. On the demand side, patients may make informal payments in order to expedite their appointments, receive better and higher-quality services, gain easier access to care, obtain more attention, or establish a relationship with physicians or other healthcare workers to ensure prompt response in case future services are needed. On the supply side, providers may seek informal payments to compensate for low wages, meet financial needs, or achieve the desired income [5, 10]. However, informal payments are primarily driven by issues on the supply side, including low budgets for healthcare organizations and low salaries for staff, so that informal payments serve as a means of collecting additional funds for healthcare organizations in general, and for physicians, in particular [9].

These payments can have numerous negative effects, including reduced health equity, decreased access to and utilization of healthcare services, disillusionment in society, particularly among the impoverished, reduced motivation among service providers to deliver high-quality services, loss of confidence and a sense of servitude among healthcare workers, corruption within the healthcare sector, provision of inaccurate information regarding disease costs, and an increase in the patient’s share of these costs [11, 12]. In general, informal payments understate the true costs of the health system. This misinformation can distort health system decisions and policies and hinder health care system reforms [11,13].

Numerous studies in developing countries and in various contexts, including Central and Eastern European countries and Central Asian countries, show a growing trend of informal payments [13,14].The prevalence of informal payments varies across countries, ranging from 2% in Peru to 96% in Pakistan [7]. Studies have reported the extent of informal payments in Bulgaria, Poland, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan as (43%), (46%), (50%), and (70%), respectively. So that patients were forced to make informal payments for services that were legally free [15]. In Iran, in a study in Urmia, this rate was estimated to be around 30% [16].

Ensuring equitable financing of health care and protecting individuals from the burden of health care costs is a critical task for health care systems around the world, and health systems have adopted a variety of strategies and programs to achieve this. In Iran, the Health System Transformation Plan has been mandatory since May 5, 2014, to reduce out-of-pocket payments for patients hospitalized in hospitals affiliated with the Ministry of Health and Medical Education. The main goal of this plan is to eliminate informal payments and increase access to health services for the community. To this end, increasing physicians' income and improving patient access, especially in deprived areas, are proposed as the main strategies in this plan.

To address the scientific gap, this study is distinctive in several ways. First, it is conducted in the post-Health System Transformation period, which allows assessment of informal payments after policy interventions aimed at reducing out-of-pocket costs. Second, it focuses specifically on Tehran, where the healthcare system is highly centralized, and there is a high concentration of specialist and subspecialist physicians, providing a unique context compared to other regions of Iran. Third, this study not only quantifies the prevalence of informal payments but also identifies their determinants, providing evidence directly relevant for policy planning and reform. By emphasizing the Tehran context, post-reform timeframe, and policy implications, this study fills a critical knowledge gap and supports targeted, evidence-based interventions.

This study seeks to provide a precise estimation of the scope and magnitude of informal payments in selected hospitals in Tehran. The results are expected to fill the existing knowledge gap, support evidence-based interventions, and inform future reforms in payment mechanisms within the Iranian healthcare system. These findings can help policymakers make evidence-based policymaking to increase equity, prevent rising healthcare costs, and reform payment mechanisms in the healthcare system.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design and Setting

This descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study was conducted in selected public hospitals in Tehran, the capital of Iran, from September to December 2024. The study aimed to determine the occurrence and amount of informal payments (primary outcome) and explore their associations with patient demographics and hospital characteristics (predictors).

2.2. Participants

The study was conducted across all 49 public hospitals in Tehran. These hospitals were categorized into two groups based on their bed capacity: large hospitals (more than 150 beds) and small hospitals (fewer than 150 beds). To account for the researchers’ available resources, such as time, financial constraints, and the level of cooperation from hospital administrators, and to enhance the reliability of the findings, 25% of the hospitals (equivalent to 12 hospitals) were selected for inclusion in the study. This proportion was calculated based on the total number of public hospitals in Tehran (49 hospitals), resulting in 12 hospitals for inclusion in the study. A stratified random sampling method proportional to size was employed for sampling. Initially, the 49 public hospitals were stratified based on Tehran's 22 districts, from which 12 hospitals were selected.

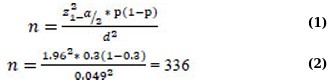

Using formulas 1 and 2 below, and considering a P-value of 0.3, which was estimated from a similar previous study [16], a confidence level of 95%, and a margin of error less than 5%, the sample size was calculated to be 336 participants.

A stratified random sampling method was used to select 336 participants. In each class, participants were systematically selected according to size. For this purpose, a list of patients discharged from hospitals was prepared, including their names, ward details, and contact telephone numbers, and each patient was assigned a unique code. Then, based on the size, the number of patients to be selected from each hospital was determined. Finally, using systematic random sampling, first a code was randomly selected, and subsequent participants were selected at intervals of 5 codes. This process continued until the sample size was completed. This method ensured a representative and unbiased selection of participants from the study population.

The Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) Guidelines were followed by the authors.

2.3. Instruments

The data collection instrument used in this study was a questionnaire previously employed in studies conducted in hospitals in Tehran and Urmia, Iran. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire had been confirmed, with Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.86 and 0.88 [16, 17]. The questionnaire consisted of 39 items divided into six sections.

Section 1 included 12 questions. The first question pertained to hospital-specific details and was completed by the researcher. Three questions addressed the patient's insurance coverage, seven questions focused on the patient's place of residence, the services provided at the hospital, and the amount paid to the hospital. Additionally, one question inquired whether informal payments had been made.

Section 1 consisted of 12 questions. The first question was about the hospital-specific information, which was completed by the researcher, three questions were related to the patient's insurance, seven questions were about the patient's residence place, the provided services in the hospital, and the amount paid to the hospital, and one question was about whether informal payments were made.

Section 2 was completed by those who made informal payments to physicians; it included six questions that related to the physician's specialty, time of payment, amount of cash payment, type of non-cash payment, and its approximate amount (Iranian Rials), whether the payment was voluntary or mandatory (requested), and the motivation for making informal payments to physicians.

Section 3 was completed by those who had made informal payments to nurses and included four questions that examined the amount of cash payment, the type of non-cash payment, and its approximate amount (Iranian Rials), whether the payment was voluntary or mandatory (requested), and the motivation for making informal payments to nurses.

Section 4 was completed by those who had made informal payments to other hospital personnel and included four questions that examined the amount of cash payment, the type of non-cash payment, and its approximate amount (Iranian Rials), whether the payment was voluntary or mandatory (requested), and the motivation for making informal payments to other personnel.

Section 5 was completed by participants who did not make informal payments. It included three questions: the first asked whether requests for payments were made by physicians or other hospital staff; the second explored the reasons for not making payments if a request was made; and the third investigated the reasons for not making voluntary payments if no request was made.

Section 6 consisted of ten questions that all participants completed. The first two questions were related to the total amount paid for care (formal and informal) and how it was financed. The next question examined the attitudes of individuals towards informal payments and their agreement or disagreement with these payments. The last seven questions were related to the demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, etc.) of the participants.

2.4. Outcome, Predictors, and Confounders

The primary outcome was the occurrence and amount of informal payments. Predictors included patient demographics and hospital-related factors such as age, gender, marital status, education level, insurance coverage, place of residence, hospital size, ward type, and length of stay. Some of these variables (insurance coverage, hospital size, and length of stay) were also considered potential confounders, as they could influence both the outcome and other predictors. No effect modifiers were explicitly pre-specified, although possible interactions between hospital type and informal payments were explored.

2.5. Procedures and Statistical Analysis

After obtaining the necessary permits, one of the researchers (MR) met with the management team of the selected hospitals. First, the objectives of the study were explained, and the confidentiality of the information collected from the patients was emphasized. Then, after coordinating with the hospital management, the researcher visited the medical records units of the selected hospitals and received a list of patients discharged from the previous month since the beginning of the study. Finally, the lists were aggregated, and a comprehensive list of discharged patients from all the hospitals studied was prepared.

Patients were selected based on the previously described sampling method, informed about the study's objectives, and assured of the confidentiality of their responses. The questionnaires were completed through telephone interviews, with verbal consent obtained from each participant. To uphold ethical standards, participation in the study and completion of the questionnaires were entirely voluntary and were conducted only with the patients' consent.

Inclusion criteria included a minimum hospital stay of 72 hours and willingness to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included receiving outpatient services for less than 72 hours, incomplete or unclear patient information, and unwillingness to participate in the study.

Data analysis was performed in two descriptive and analytical methods. For this purpose, SPSS version 23 software was used. In descriptive analysis, the frequency, percentage, and mean of informal payments were calculated based on study variables, including healthcare personnel (physicians, nurses, and others), type of payment (cash and non-cash), patients’ demographic characteristics who made informal payments, such as gender, marital status, education, insurance coverage, place of residence, length of hospital stay, discharge department, and timing of informal payment.

In the analytical analysis, a coefficient was used to examine the correlation of informal payments with the variables of patients’ age and length of stay in the hospital. The Mann-Whitney test was also used to examine the difference in the mean of informal payments based on gender, marital status of patients, supplementary insurance coverage, and time of informal payment. Finally, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to measure the difference in the mean of informal payments based on the patients' place of residence.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

The findings show that out of 336 patients surveyed, 67 patients (19.94%) made informal payments. Among those who made informal payments, the majority were over 50 years of age (41.79%), male (52.24%), resident in Tehran (64.18%), married (70.10%), had primary education (40.30%), and were covered by social security insurance (basic) (55.22%). In addition, 33.34% of patients who made informal payments were covered by supplementary insurance. The average length of stay of patients who made informal payments was 21.55 days (Table 1).

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <20 | 10 | 14.93 |

| 20-35 | 12 | 17.91 | |

| 36-50 | 17 | 25.37 | |

| >50 | 28 | 41.79 | |

| Gender | Male | 35 | 52.24 |

| Female | 32 | 47.76 | |

| Place of Residence | Tehran | 43 | 64.18 |

| Provincial Capital | 11 | 16.42 | |

| County | 9 | 13.43 | |

| Village | 4 | 5.97 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 20 | 29.90 |

| Married | 47 | 70.10 | |

| Education | Illiterate | 8 | 11.94 |

| Primary School | 17 | 40.30 | |

| Secondary School | 15 | 22.39 | |

| High School | 10 | 14.92 | |

| University Degree | 7 | 10.45 | |

| Basic Insurance Type | Social Security Insurance | 37 | 55.22 |

| Health of Iranians Insurance | 20 | 29.85 | |

| Self-Employed Insurance | 1 | 1.49 | |

| Rural Insurance | 4 | 5.98 | |

| Other | 3 | 4.48 | |

| Without Insurance Coverage | 2 | 2.98 | |

| Supplementary Insurance | Yes | 23 | 34.33 |

| No | 44 | 65.67 | |

| Length of Stay (Days) | 3-10 | 35 | 52.24 |

| 11-20 | 7 | 10.45 | |

| 21-30 | 9 | 13.43 | |

| >30 | 16 | 23.88 | |

| Discharge Department | Surgery | 45 | 67.16 |

| ICU | 3 | 4.48 | |

| Maternity | 4 | 5.98 | |

| CCU | 4 | 5.98 | |

| Orthopedics | 3 | 4.48 | |

| Neurology | 2 | 2.97 | |

| Internal Medicine | 3 | 4.48 | |

| Urology | 1 | 1.49 | |

| Nephrology | 1 | 1.49 | |

| Rheumatology | 1 | 1.49 | |

| Timing of Informal Payments | Before Hospitalization | 5 | 7.46 |

| After Hospitalization | 62 | 92.54 | |

| Informal Payments to The Physician | Yes | 33 | 49.25 |

| No | 34 | 50.75 | |

| Informal Payments to The Nurse | Yes | 31 | 46.27 |

| No | 36 | 53.73 | |

| Informal Payments to Other Personnel | Yes | 22 | 32.83 |

| No | 45 | 67.17 | |

| Total | ………… | 67 | 100 |

3.2. Informal Payments

The total amount of informal cash payments to physicians, nurses, and other personnel was estimated at 840,000,000 Iranian Rials (equivalent to eighty-four million Tomansor 1,235.75 $US). The breakdown of these payments to physicians, nurses, and other staff is as follows:

3.3. Informal Payments to Physicians

Of the 33 informal payments made to physicians, the majority (32 cases) were in cash, amounting to 1,029.76 $US (700,000,000 Iranian Rials (equivalent to 70 million Tomans)), representing 96.97% of the payments. All the 32 cash payments were made at the request of the physicians. Among these, the highest single cash payment was 29.42 $US (20,000,000 Iranian Rials (equivalent to 2 million Toman)), accounting for 37.5% of the total payments (Table 2).

According to Table 3, the majority of cash payments to physicians were made by patients in the age group over 50 years (40.63%), male patients (56.25%), those residing in Tehran (68.76%), married patients (81.25%), patients with primary school education (43.75%), those covered by Social Security insurance (59.37%), and those without supplementary insurance (68.75%). Most payments were from patients with a hospital stay of 3 to 10 days (53.13%), made after hospitalization (87.50%), and from patients in the surgery department (78.13%) (Table 3).

| Informal Payment Details | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Payment Type | Gifts (Flowers, Sweets, etc.) | 1 | 3.03 |

| Cash Payments | 32 | 96.97 | |

| Total | 33 | 100 | |

| Payment Amount | 14.71 $US (10 Million Iranian Rials) | 2 | 6.25 |

| 22.06 $US (15 Million Iranian Rials) | 5 | 15.62 | |

| 29.42 $US (20 Million Iranian Rials) | 12 | 37.50 | |

| 36.77 $US (25 Million Iranian Rials) | 5 | 15.62 | |

| 44.13 $US (30 Million Iranian Rials) | 8 | 25 | |

| Total | 32 | 100 | |

| Motivation to Pay | Forced Payments (Physicians' Requests) | 32 | 96.97 |

| Voluntary Payments (Thanks and Appreciation) | 1 | 3.03 | |

| Total | 33 | 100 | |

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent | Payment Amount $US (Iranian Rials) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <20 | 3 | 9.36 | 110.33 (75,000,000) |

| 20-35 | 7 | 21.88 | 205.95 (140,000,000) | |

| 36-50 | 9 | 28.13 | 286.87 (195,000,000) | |

| >50 | 13 | 40.63 | 426.62 (290,000,000) | |

| Gender | Male | 18 | 56.25 | 573.74 (390,000,000) |

| Female | 14 | 43.75 | 456.05 (310,000,000) | |

| Place of Residence | Tehran | 22 | 68.76 | 698.78 (475,000,000) |

| Provincial Capital | 5 | 15.62 | 161.82 (110,000,000) | |

| County | 5 | 15.62 | 169.18 (115,000,000) | |

| Marital status | Single | 6 | 18.75 | 183.89 (125,000,000) |

| Married | 26 | 81.25 | 845.90 (575,000,000) | |

| Education | Illiterate | 2 | 6.25 | 44.13 (30,000,000) |

| Primary School | 14 | 43.75 | 448.69 (305,000,000) | |

| Secondary School | 8 | 25 | 235.38 (160,000,000) | |

| High School | 5 | 15.62 | 183.89 (125,000,000) | |

| University degree | 3 | 9.38 | 117.69 (80,000,000) | |

| Basic Insurance Type | Social Security Insurance | 19 | 59.37 | 610.52 (415,000,000) |

| Health of Iranians Insurance | 6 | 18.75 | 205.96 (140,000,000) | |

| Rural Insurance | 3 | 9.38 | 73.55 (50,000,000) | |

| Other | 3 | 9.38 | 95.62 (65,000,000) | |

| Without Insurance Coverage | 1 | 3.12 | 44.13 (30,000,000) | |

| Supplementary Insurance | Yes | 10 | 31.25 | 338.36 (230,000,000) |

| No | 22 | 68.75 | 691.43 (470,000,000) | |

| Length of Stay (Days) | 3-10 | 17 | 53.13 | 522.25 (355,000,000) |

| 11-20 | 4 | 12.50 | 139.75 (95,000,000) | |

| 21-30 | 5 | 15.62 | 132.40 (90,000,000) | |

| >30 | 6 | 18.75 | 235.38 (160,000,000) | |

| Discharge Department | Surgery | 25 | 78.13 | 831.19 (565,000,000) |

| Maternity | 3 | 9.38 | 80.91 (55,000,000) | |

| CCU | 1 | 3.12 | 44.13 (30,000,000) | |

| Orthopedics | 1 | 3.12 | 14.71 (10,000,000) | |

| Neurology | 2 | 6.25 | 58.85 (40,000,000) | |

| Timing of Informal Payments | Before Hospitalization | 4 | 12.50 | 183.89 (125,000,000) |

| After Hospitalization | 28 | 87.50 | 845.90 (575,000,000) |

Analysis of the relationship between patient demographic variables and informal payments to physicians showed no significant correlation with age (p = 0.909, OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.85–1.21), gender (p = 0.925, OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.67–1.43), marital status (p = 0.760, OR = 1.08, 95% CI: 0.74–1.58), place of residence (p = 0.767, OR = 1.04, 95% CI: 0.81–1.34), having supplementary insurance (p = 0.509, OR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.57–1.34), or the timing of informal payments (p = 0.241, OR = 1.45, 95% CI: 0.80–2.61). However, a statistically significant correlation was found between the length of hospital stay and informal payments to physicians (p = 0.021, OR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.02–1.23), indicating that as the length of stay increased, the likelihood and amount of informal payments also tended to increase. The effect size (Cohen’s d) for length of stay was 0.42, indicating a moderate effect.

3.4. Informal Payments to Nurses

Of the 31 informal payments made to nurses, the majority (13 cases) were in cash, amounting to 176.53 $US (120,000,000 Iranian Rials (equivalent to 12 million Tomans)), representing 41.94% of the total payments. All 13 cash payments were made at the request of the nurses. Among these payments, the highest single cash payment was 14.71 $US (10,000,000 Iranian Rials (equivalent to 1 million Toman)), accounting for 53.85% of the cash payments (Table 4).

According to Table 5, the majority of cash payments to nurses were made by patients in the age group over 50 years (46.15%), female patients (61.54%), those residing in Tehran (76.92%), married patients (53.85%), patients with high school education (46.15%), and those without supplementary insurance (53.85%). Most payments were from patients with a hospital stay of 3 to 10 days (61.54%), made after hospitalization (100%), and from patients in the surgery department (46.15%) (Table 5).

3.5. Informal Payments to Other Hospital Staff

Based on the results, of the 22 informal payments made to other hospital staff, the majority (18 cases, 81.82%) were in the form of gifts. Among the 4 cases of cash informal payments made to other staff, each payment amounted to 7.35 $US (5,000,000 Iranian Rials (equivalent to 500,000 Tomans)), totaling 29.42 $US (20,000,000 Iranian Rials (equivalent to 2 million Tomans)) (Table 6).

According to Table 7, of the 4 cash informal payments made to other staff, the majority were from patients in the age group over 50 years (50%), male patients (75%), residing in Tehran (100%), with a high school education (50%), with supplementary insurance (75%), with a length of stay between 3 and 10 days (100%), made after hospitalization (100%), and from patients in the surgery department (50%) (Table 7).

| Informal Payment Details | Frequency | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payment Type | Gifts (Flowers, Sweets, etc.) | 18 | 58.06 | |

| Cash Payments) | 13 | 41.94 | ||

| Total | 31 | 100 | ||

| Payment Amount | 7.35 $US (5 Million Iranian Rials) | 3 | 23.08 | |

| 10.29 $US (7 Million Iranian Rials) | 1 | 7.69 | ||

| 11.76 $US (8 Million Iranian Rials) | 1 | 7.69 | ||

| 14.71 $US (10 Million Iranian Rials) | 7 | 53.85 | ||

| 29.42 $US (20 Million Iranian Rials) | 1 | 7.69 | ||

| Total | 13 | 100 | ||

| Motivation to Pay | Forced Payments (Nurses' Requests) | 6 | 19.35 | |

| Voluntary Payments | Thanks, and Appreciation | 8 | 25.81 | |

| Hoping to Receive Better Quality Services | 17 | 54.84 | ||

| Total | 31 | 100 | ||

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent | Payment Amount $US (Iranian Rials) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <20 | 3 | 23.08 | 48.54 (33,000,000) |

| 20-35 | 1 | 7.69 | 7.35 (5,000,000) | |

| 36-50 | 3 | 23.08 | 36.77 (25,000,000) | |

| >50 | 6 | 46.15 | 83.85 (57,000,000) | |

| Gender | Male | 5 | 38.46 | 85.84 (40,000,000) |

| Female | 8 | 61.54 | 117.69 (80,000,000) | |

| Place of Residence | Tehran | 10 | 76.92 | 142.70 (97,000,000) |

| County | 1 | 7.69 | 14.71 (10,000,000) | |

| Village | 2 | 15.39 | 19.12 (13,000,000) | |

| Marital Status | Single | 6 | 46.15 | 80.91 (55,000,000) |

| Married | 7 | 53.85 | 95.62 (65,000,000) | |

| Education | Primary School | 2 | 15.39 | 36.77 (25,000,000) |

| Secondary School | 3 | 23.08 | 41.19 (28,000,000) | |

| High School | 6 | 46.15 | 80.91 (55,000,000) | |

| University Degree | 2 | 15.39 | 17.65 (12,000,000) | |

| Basic Insurance Type | Social Security Insurance | 6 | 46.15 | 98.56 (67,000,000) |

| Health of Iranians Insurance | 6 | 46.15 | 70.61 (48,000,000) | |

| Rural Insurance | 1 | 7. 69 | 7.35 (5,000,000) | |

| Supplementary Insurance | Yes | 6 | 46.15 | 98.56 (67,000,000) |

| No | 7 | 53.85 | 77.96 (53,000,000) | |

| Length of Stay (Days) | 3-10 | 8 | 61. 54 | 113.27 (77,000,000) |

| 11-20 | 1 | 7. 69 | 14.71 (10,000,000) | |

| 21-30 | 3 | 23.08 | 36.77 (25,000,000) | |

| >30 | 1 | 7. 69 | 11.76 (8,000,000) | |

| Discharge Department | Surgery | 6 | 46.15 | 66.20 (45,000,000) |

| ICU | 2 | 15.39 | 26.48 (18,000,000) | |

| CCU | 2 | 15.39 | 25 (17,000,000) | |

| Orthopedics | 2 | 15.39 | 44.13 (30,000,000) | |

| Urology | 1 | 7. 69 | 14.71 (10,000,000) | |

| Timing of Informal Payments | Before Hospitalization | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| After Hospitalization | 12 | 100 | 176.53 (120,000,000) |

| Informal Payment Details | Frequency | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payment Type | Gifts (Flowers, Sweets, etc.) | 18 | 81.82 | |

| Cash Payments) | 4 | 18.18 | ||

| Total | 22 | 100 | ||

| Payment Amount | 5 Million Iranian Rials | 4 | 100 | |

| Total | 4 | 100 | ||

|

Motivation to Pay |

Forced Payments | 0 | 0 | |

| Voluntary Payments | Thanks, and Appreciation | 6 | 27.27 | |

| Hoping to Receive Better Quality Services | 16 | 72.73 | ||

| Total | 22 | 100 | ||

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent | Payment Amount $US (Iranian Rials) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <20 | 1 | 25 | 7.35 (5,000,000) |

| 20-35 | 1 | 25 | 7.35 (5,000,000) | |

| 36-50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| >50 | 2 | 50 | 14.71 (10,000,000) | |

| Gender | Male | 3 | 75 | 22.06 (15,000,000) |

| Female | 1 | 25 | 7.35 (5,000,000) | |

| Place of Residence | Tehran | 4 | 100 | 29.42 (20,000,000) |

| Marital status | Single | 2 | 50 | 14.71 (10,000,000) |

| Married | 2 | 50 | 14.71 (10,000,000) | |

| Primary School | 1 | 25 | 7.35 (5,000,000) | |

| Secondary School | 1 | 25 | 7.35 (5,000,000) | |

| High School | 2 | 50 | 14.71 (10,000,000) | |

| Basic Insurance Type | Social Security Insurance | 2 | 50 | 14.71 (10,000,000) |

| Health of Iranians Insurance | 2 | 50 | 14.71 (10,000,000) | |

| Supplementary Insurance | Yes | 3 | 75 | 22.06 (15,000,000) |

| No | 1 | 25 | 7.35 (5,000,000) | |

| Length of Stay (Days) | 3-10 | 4 | 100 | 29.42 (20,000,000) |

| Discharge Department | Surgery | 2 | 50 | 14.71 (10,000,000) |

| CCU | 1 | 25 | 7.35 (5,000,000) | |

| Orthopedics | 1 | 25 | 7.35 (5,000,000) | |

| Timing of Informal Payments | Before Hospitalization | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| After Hospitalization | 4 | 100 | 29.42 (20,000,000) |

| Reasons | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Discontinuance of personnel due to follow-up of the patient or his/her companion from the hospital (administration, nursing office, and hospital security) | 4 | 25 |

| Unwillingness of the patient or his/her companion to pay due to the patient's favorable condition | 3 | 18.75 |

| Having an acquaintance at the hospital or university | 2 | 12.50 |

| Financial inability of the patient or his/her companion | 5 | 31.25 |

| Feeling that the quality of service is appropriate and does not need these types of payments | 2 | 12.50 |

| Total | 16 | 100 |

3.6. Facing Informal Payment Requests

Of the 336 patients interviewed, 16 reported encountering requests for informal payments. However, for various reasons (as detailed in Table 8), they chose not to comply with these requests.

4. DISCUSSION

According to the findings, 19.94% of patients (67 out of 336) reported making informal payments. This percentage is higher than the figure reported by Zanganeh Baygi et al. (2018), who found that only 2% of patients made informal payments in hospitals in Zahedan [18]. However, this rate was underreported in the study by Yousefi et al. (2020), which found that 34% of hospitalized patients made informal payments [19]. In the study by Ghiasipour et al. (2011), this rate was also reported as 21% [20]. Or similarly, Hajian Dashtaki et al. (2018) found in their study that 27.2% of patients made informal payments [21]. According to the study by Parsa et al. (2017), a relatively high prevalence of informal payments was reported, at 63.8% [22]. The high prevalence of informal payments demonstrated in this study warrants attention and targeted interventions by policymakers. There is considerable evidence that informal payments exacerbate the financial burden of health care, particularly for the economically disadvantaged, and have negative impacts on equity and health outcomes [9]. Regardless of the motivations behind informal payments, they have widespread and adverse consequences for the health system. These consequences include increased health care costs, inequities in access to essential services, and ultimately inequities in health outcomes. Therefore, the most important consequence of this phenomenon is reduced access to health care services due to increased costs of services, which in turn exacerbates inequalities in health outcomes. As a result, individuals from low socioeconomic groups are disproportionately affected and face greater health challenges. Furthermore, informal payments reduce social justice and undermine public trust in the healthcare system and the government as a guardian of health [23].

Based on the findings of our study, among the 67 patients who made informal payments, a larger number (33 patients) made such payments to physicians, mostly in cash. This is consistent with the findings of Yousefi et al. (2020), which similarly reported that most informal payments were made to physicians; among these, general surgeons and urologists received the highest amounts, and these informal payments were often mandatory [19]. In a study by Parsa et al. (2017), it was shown that 63.8% of physicians who had the opportunity to receive informal payments did so at least once [20]. Numerous similar findings were observed in various contexts. For example, Liaropoulos et al. (2008) found that 36% of patients in Greece had made informal payments to physicians at least once [14]. Ozgen et al. (2010) also reported in their study that 75% of cash payments made to physicians in hospitals were made as informal payments [9]. In addition, Tatar et al. (2007) reported that informal payments were received more by physicians and surgeons [24].

Our study found that of the 67 patients who made informal payments, 31 made such payments to nurses, mostly in cash. Similarly, a study by Yousefi et al. (2020) also showed that after physicians, nurses received the highest amount of informal payments [19]. Liaropoulos et al.’s (2008) study found that 11% of patients in public hospitals made informal payments to nurses [14]. In contrast, this rate was reported to be only 5% in the study by Khodamoradi et al. (2015) [25]. Or in the study by Zanganeh Baighi et al. (2019), the average amount of informal payments to nurses was estimated at US$64 [18]. These findings reflect the profound impact of systemic and socioeconomic factors on this phenomenon. Evidence shows that informal payments are often seen in healthcare systems when financial support for health service providers is reduced due to adverse economic conditions, leading service providers to seek alternative sources of income. Indeed, in the informal market that is thus created in the healthcare sector, as in other informal sectors, informal payments to physicians, nurses, and other members of the healthcare team often remain unmonitored, illegal, and unreported.

The study findings also showed that of the 67 patients who made informal payments, 22 made these payments to other healthcare workers, mostly in the form of gifts. This is consistent with the findings of Liaropoulos' (2008) study, which showed that 8% of patients in public hospitals made informal payments to other staff [14]. In the study of Ghiasipour et al. (2011), it was shown that all 63 patients who made informal payments made these payments to hospital staff, and one patient made informal payments to a security guard [20]. In the study of Ozgen et al. (2010), this rate was reported to be 9% [9]. And in the study of Khodamoradi et al. (2015), the rate of informal payments to other hospital staff was estimated to be 17% [25]. These findings indicate that informal payments in the health system are not limited to physicians and nurses, but also include other personnel. As mentioned, one of the factors influencing the prevalence of such payments is the unfavorable economic situation and relatively low wages among healthcare workers, which have been pointed out in numerous studies [20]. Inadequate compensation for services provided, lack of regular payment of salaries, and inadequate government support measures have led some healthcare providers to turn to informal payments as a necessary source of income to fill financial gaps. The prevalence of this phenomenon among healthcare workers is a warning about the need to address issues related to healthcare worker salaries, which can help create a more transparent and equitable healthcare environment [25].

Our study findings showed that there is a significant relationship between the amount of informal payments to physicians and the length of hospital stay, which is consistent with the results of Ghiasipour et al. (2009) [20]. Evidence suggests that the severity of the patient's condition and the perceived need for specialized care or higher quality services are factors that influence patients' acceptance of informal payment requests. According to the results of the study by Vian et al. (2006), supporting quality improvement programs can be an effective policy to reduce informal payments. The findings of this study showed that patients are more likely to make informal payments when they expect to receive better and more timely healthcare services in this way [26]. Therefore, targeted interventions and strategies to increase the quality of healthcare and improve access to public services can help reduce the prevalence of informal payments.

5. LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations. First, data were collected through self-report questionnaires, so participants are subject to recall bias or underreporting, especially on a sensitive topic such as informal payments. Second, this study was conducted in a limited number of public hospitals in Tehran, and the results may not be generalizable to all hospitals in Iran. Third, the study was conducted cross-sectionally, which does not allow for the establishment of causal relationships between the variables under study. Finally, cultural and social factors influencing informal payment practices were not examined in depth, which may limit a comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon.

CONCLUSION

According to the findings of this study, about 20 percent of patients have made informal payments to healthcare workers. Given the negative effects of informal payments on equity and governance, it is essential that policymakers pay special attention to this phenomenon and adopt strategies to reduce its prevalence. While currently, limited efforts have been made to control informal payments, it is recommended that future strategies include regulating salaries, benefits, and medical tariffs, creating enforceable laws and regulations to combat informal payments, emphasizing programs to improve service quality, motivating healthcare workers, promoting accountability in the healthcare system, and changing public perception toward greater transparency and fairness in the healthcare system.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: A.R.Y.: Designed the study and prepared the initial draft; A.R.Y. and M.R.: Contributed to data collection and data analysis; T.R., O.A., and J.B.: Supervised the study and finalized the article. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| IRR | = Iranian Rial |

| USD | = United States Dollar |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SD | = Standard Deviation |

| MoHME | = Ministry of Health and Medical Education |

| TUMS | = Tehran University of Medical Sciences |

| HSTP | = Health System Transformation Plan |

ETHICAL APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study is approved by Tehran University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee with the code of IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1403.100.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All the data and supporting information are provided within the article. Additional data can be requested from the corresponding author.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was extracted from a research project approved by the National Center for Health Insurance Research (ID: 403000049). The researchers would like to thank contributed to the National Center for Health Insurance Research.