All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Perception of Community Pharmacy Staff toward the COVID-19 Vaccination and Adverse Events: Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Survey approach in the Twin Cities of Pakistan

Abstract

Introduction

Progress in vaccine development has expanded since the outbreak of COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2. However, inadequate vaccine development, the lack of a comprehensive risk assessment, and limited awareness among community pharmacists of Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs) associated with vaccines negatively impacted patients' quality of life. This research intends to measure the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of community pharmacy personnel towards the process of COVID-19 vaccination and its adverse effects.

Methods

From October 2021 to November 2022, a cross-sectional, survey-based research was carried out using 400 respondents.

Results

400 respondents were involved, among them about 59% were male, and 65% were female, with an age range of 25 to 39 years. Over 67% of participants reported themselves as vaccinated against COVID-19. Moreover, 62% of respondents were motivated to participate in public vaccination programs, and about 66% believed that pharmacy professionals contribute to preventing viral spread. Lack of awareness was considered to be one of the leading factors associated with vaccine-related ADRs.

Discussion

The study revealed the progressive role of pharmacy professionals in vaccine advocacy and delivery, contributing to an overall improvement in vaccination rates.

Conclusion

According to current findings, pharmacy professionals overall exhibited good knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding the COVID-19 vaccines. It was especially observed that pharmacists performed significantly better in terms of knowledge compared to other healthcare professionals. Strengthening this knowledge would result in more successful delivery of the immunization services throughout Pakistan.

1. INTRODUCTION

The respiratory infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 has brought the world to a standstill, followed by the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring it a pandemic [1, 2]. COVID-19-associated symptoms generally appear within 2 to 14 days of exposure, ranging from mild to severe, including chills, cough, fever, fatigue, headache, loss of taste or smell, muscle aches, sore throat, and shortness of breath [1, 3]. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed significant weaknesses in the global health care system and amplified existing social inequalities. Extended lockdowns resulted in widespread job losses, contributing to a global economic downturn [4, 5]

Throughout the pandemic, pharmacies appeared to be the easily accessible healthcare hubs, providing reliable, up-to-date, and authentic health-related information. Furthermore, to maintain social isolation and ensure social distancing, pharmacies worldwide adapted medication delivery to home and telehealth services [6, 7]. Existing literature highlighted the effective role of community pharmacists in delivering immunization services, particularly in high-income countries [8]. These pharmacists have played a vital role in curbing the pandemic through pharmaceutical care, patient counseling, and vaccination services. Surveys from Northern Ireland [9] and Puerto Rico revealed high willingness among pharmacists (80.7% and 76.1%, respectively) to administer COVID-19 vaccines, underscoring their critical public health role [10, 11].

The existing literature corroborates immunization services provided by community pharmacists at pharmacies in high-income countries [12, 13]. Community pharmacists have been an effective deterrent to containing the impact of the pandemic by providing pharmaceutical care, updated guidance, and immunization support to the public [10, 14]. In a cross-sectional study of 130 pharmacists from Northern Ireland, 80.7% were willing to administer the COVID-19 vaccination. Another study from Puerto Rico noted a 76.1% willingness of pharmacists to administer the COVID-19 vaccination [14, 15]. Thus, we acknowledge pharmacists’ role in major public health crises. A recent survey of public health leaders identified pharmacists as playing a key role in COVID-19 vaccine administration and pandemic planning [10, 16].

In Pakistan, the pandemic led to widespread unemployment and the suspension of all economic, educational, and transport activities [17]. As a resource-limited country allocating only 0.6% of its GDP to healthcare, Pakistan faces challenges such as limited infrastructure, outdated treatment facilities, and a shortage of healthcare personnel. Community pharmacy services remain underdeveloped due to regulatory gaps, pharmacist shortages, and minimal governmental support [18]. A cross-sectional survey of 393 pharmacists from two provinces revealed strong knowledge but weak attitudes and practices concerning COVID-19 [14, 18, 19].

Pharmacies are uniquely positioned to reach underserved populations. Evidence shows that pharmacy-led immunization programs are particularly effective in vaccinating older, high-risk adults who frequently rely on pharmacy services [20, 21].

In a developing country like Pakistan, the COVID-19 pandemic led to widespread unemployment, together with the suspension of all academic and transport activities, resulting in challenges such as inadequate infrastructure, unexpected therapeutic outcomes, and a shortage of healthcare professionals, including the underdevelopment and insufficient availability of community pharmacists through regulatory gaps and minimal governmental support. Although some studies indicated strong knowledge among community pharmacists, weaker attitudes and practices regarding COVID-19 were observed. A published report on the pharmacist's evolving role in the COVID-19 pandemic was heavily sourced from developed countries, citing established pharmacy-led immunization programs and advanced healthcare frameworks. However, the findings of these studies could not be effectively applied in Pakistan due to resource constraints, a weak healthcare system, and varying levels of public trust in community pharmacists. A gap arises in the judgment of how the Pakistani pharmacist played a role in shaping perceptions and practices of robust, context-specific research during the pandemic. Keeping the aforementioned objective in view, a Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) analysis was conducted in Pakistan regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. The current study's findings might help identify locally relevant evidence that pharmacists can use to help establish and inform national strategies for effectively managing such situations in future public health emergencies.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

2.1.1. Data Collection

Data collection, i.e., the survey, was initiated on October 10, 2021, and collection and acceptance of responses were stopped on November 30, 2022, once the necessary number of samples was achieved. The CPs were sent an online questionnaire via several methods: social media sources (WhatsApp, Facebook, Gmail, and LinkedIn). Pharmacists who were effectively involved in hospitals, the pharmaceutical industry, and marketing were not included in this study.

2.1.2. Data Collection Tool

A questionnaire was designed using the COVID-19 guidelines of the FIP for pharmacists and the pharmacy workforce (10), together with the national COVID-19 action plan in Pakistan (Supplementary Material).

A pilot study was performed on 40 pharmacists, 20 from each city, with the reliability coefficient being calculated using SPSS, version 21 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) and Cronbach alpha was 0.745, Corp, Armonk, NY) [22].

2.2. Study Design, Setting, and Respondents

2.2.1. Sample Size

The current study followed a descriptive cross-sectional study design. The study was conducted at community pharmacies located in the twin cities of Pakistan (Islamabad and Rawalpindi). The participants included community pharmacy personnel, including pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and dispensers [23]. The sample size was calculated using the Raosoft sample size calculator using a 95% confidence level and a 5% error margin, resulting in a minimum obligatory sample size of 400 participants. The collected data included an additional 20% to cover incomplete responses and related questionnaire errors [22].

A convenient sampling technique was employed following the procedure adopted by Muhammad et al. (2022), with certain modifications for participant selection [14, 22]. Briefly, the questionnaire included demographics and the KAP-associated questions.

2.3. Study Tool

A pre-validated questionnaire was utilized to assess the existing knowledge of community pharmacy staff regarding COVID-19 vaccines [24]. The tool also examined how this knowledge influenced their attitudes and practices, as well as their understanding of vaccine-related adverse events [25].

2.4. Research and Ethical Declarations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards described in the Helsinki Declaration and relevant national guidelines for research involving human participants. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Hamdard University, Islamabad (Approval Number: ERC-FOP-03-01). Before participation, all respondents were provided with clear information about the study's objective and purpose, the voluntary nature of their participation, and assurances of confidentiality and anonymity. Written informed consent, duly signed by the participant and principal investigator, was obtained from all participants before data collection commenced. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any point without any consequences. The collected data was kept confidential and was used solely for research purposes. The completed questionnaires were securely stored in a restricted-access location, accessible only to the principal investigator [26].

2.5. Pharmacist Eligibility and Recruitment

2.5.1. Inclusion Criteria

The pharmacists currently working in community pharmacies (either full-time or part-time) have been included in the study, including properly licensed pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and dispensers directly involved in patient care as well as medication dispensing. The pharmacists with at least 6 months of work experience have been included. Furthermore, community pharmacists who voluntarily signed written informed consent have been included in the study and provided complete responses [23].

2.5.2. Exclusion Criteria

Participants who have been excluded from the study included Non-Community Pharmacists and pharmacy staff employed in hospital, academic, regulatory, or pharmaceutical industry settings. Furthermore, pharmacy students or internees and pharmacists who failed to practice independently were excluded from the study. Furthermore, students with less than six months of working experience in a community pharmacy have not yet been included. Additionally, pharmacists on leave during the data collection period, individuals who refused to provide informed consent, those who withdrew consent at any point, or those who provided incomplete information have not yet been included [23].

2.5.3. Data Collection Procedure and Analysis

Data were collected by the principal investigator, who received formal training from the study supervisor. Participants self-administered the questionnaire, which was collected on the same day to minimize potential bias. Collected data were cleaned, coded, and analyzed using SPSS version 26.0. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, were used to summarize the data [27].

2.6. Data Storage

All completed data collection forms were securely stored in a restricted-access location, available only to the principal investigator [28].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

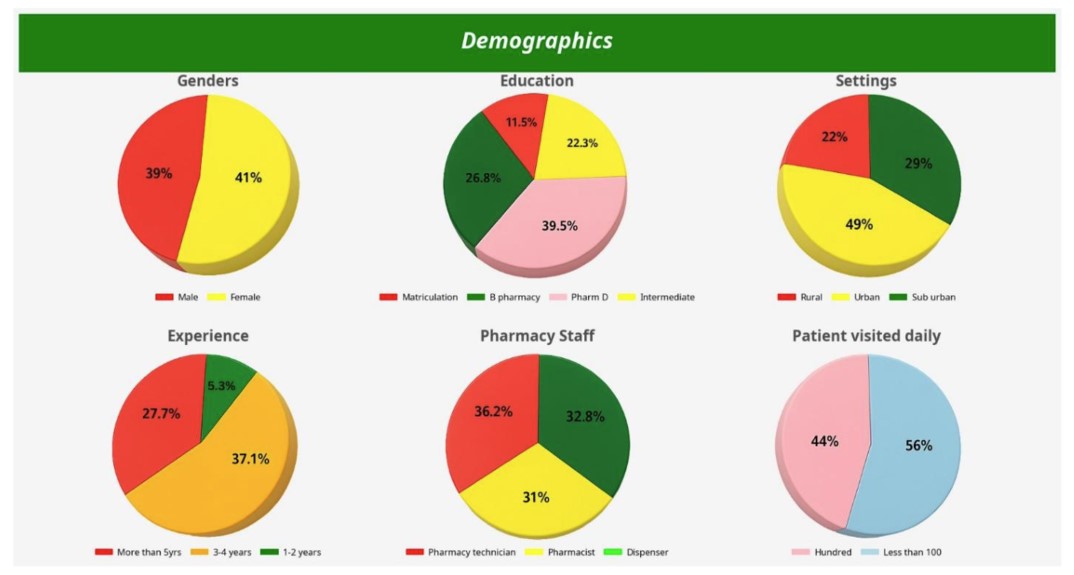

A total of 400 participants from community pharmacies participated in the current study, including pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and dispensers. The majority of participants were between the ages of 25 and 39, with almost equal representation from both genders. Demographic division classification of community pharmacists and pharmacy technicians on the basis of gender, education, region, experience, etc., has been described in Fig. (1). The gender-based classification presented in the results indicated that 41% of the sample consisted of females, with the remainder 59% comprising males. The education-based division indicated that 39.5% of participants held a category-B pharmacy degree, 26.8% were individuals with intermediate-level education, 22.3% possessed a Pharm-D degree, while 11. 5% possessing only matric level education. Regionally, approximately 49% of individuals lived in urban areas, 29% in suburban areas, and 22% in rural areas. According to the job experience, approximately 27.7% of participants had more than 5 years of experience, while 37.1% had 3-4 years, and the remaining 5.3% had only 1-2 years of experience. Among the pharmacy staff, the largest group was pharmacy technicians (36.2%), followed by pharmacists (31%) and dispensers (32.8%). Furthermore, about 44% of patients visited pharmacies, with the remaining 56% presenting the vice versa system.

A figure representing the demographic variables, including gender, education, regional, and professional experience of pharmacy staff, including pharmacy technicians and dispensers.

3.2. Knowledge of Pharmacy staff towards COVID-19 vaccines

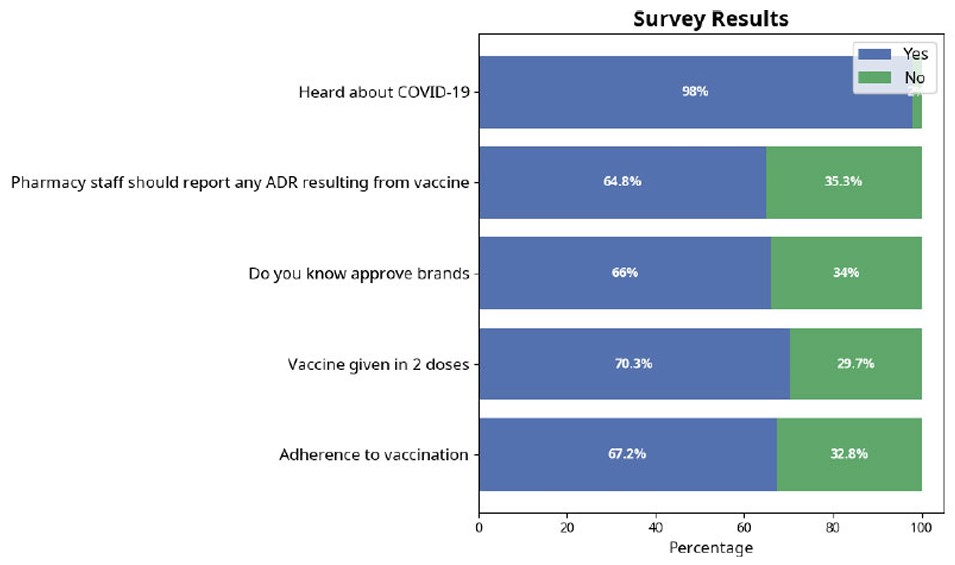

The majority of individuals indicated familiarity with the COVID-19 vaccine; however, there was significant variation across roles (Fig. 2). Notably, 36.7% of pharmacists reported awareness of the vaccine compared to pharmacy technicians and dispensers (31.6%), respectively. A significant proportion also identified that COVID-19 is caused by a β coronavirus, particularly pharmacists (39.6%) and pharmacy technicians (38.6%), with the detailed results being mentioned in Table 1A and Fig. (2).

Diagrammatic representation of knowledge of pharmacy staff regarding COVID-19 vaccination.

Adherence to vaccination schedules was observed to be comparatively higher among pharmacists (42.8%) than dispensers (20.8%). Pharmacists also presented a better understanding of the vaccine dosage schedule (40.9%) and were more aware of the fact that vaccines better enhance the body’s natural defenses (40.3%) (Table 1B and Fig. 2).

| Table (1A). | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | n (%) Yes | n (%) No | P-value | |||

| Have you heard about the COVID-19 vaccine? | 0.001 | |||||

| Pharmacist | 138(36.7) | 1(16.8) | ||||

| Pharmacy technicians | 119(31.6) | 9(31.2) | ||||

| Dispenser | 119(31.6) | 14(52) | ||||

| COVID-19 is caused by the beta coronavirus | 0.001 | |||||

| Pharmacist | 116(39.6) | 2(1.5) | ||||

| Pharmacy technicians | 113(38.6) | 38(35.9) | ||||

| Dispenser | 64(21.8) | 67(62.6) | ||||

| Adherence to COVID-19 vaccination | 0.001 | |||||

| Pharmacist | 115(42.8) | 4(3.7) | ||||

| Pharmacy technicians | 98(36.4) | 51(39.9) | ||||

| Dispenser | 56(20.8) | 75(57.3) | ||||

| What do you think about the dosage schedule of the COVID-19 vaccine? | 0.001 | |||||

| Pharmacist | 115(40.9) | 14(11.8) | ||||

| Pharmacy technicians | 110(39.1) | 30(25.2) | ||||

| Dispenser | 56(19.9) | 75(63.0) | ||||

| Table (1B). | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | n (%) Yes | n (%) No | P-value |

| The COVID-19 vaccination reduces the threat of contracting illness by enhancing the natural defense of the body. | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 110(40.3) | 14(11.0) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 91(33.3) | 54(42.5) | |

| Dispenser | 72(26.4) | 59(46.5) | |

| Do you know approved brands of COVID-19 vaccines? | 0.03 | ||

| Pharmacist | 100(36.4) | 24(19.2) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 92(33.5) | 53(42.4) | |

| Dispenser | 83(30.2) | 48(38.4) | |

| Every vaccine must undergo extensive and rigorous testing before its introduction. | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 107(39.8) | 17(13) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 88(32.7) | 57(43.5) | |

| Dispenser | 74(27.5) | 57(43.5) | |

| Any clinically significant adverse event must be reported by pharmacy staff after administration of the COVID-19 vaccine. | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 107(41.3) | 32(22.7) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 92(35.5) | 38(27) | |

| Dispenser | 60(23.2) | 71(50.4) | |

| Do you have updated information on COVID-19 vaccines? | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 99(38.4) | 25(17.6) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 93(36) | 52(36.6) | |

| Dispenser | 66(25.6) | 65(45.8) | |

Knowledge of approved vaccine brands was highest among pharmacists (36.4%) and lowest among dispensers (30.2%). Similarly, a greater number of pharmacists better understand the importance of rigorous testing before vaccine approval (39.8%), with approximately 41.3% of the population reporting the importance of reporting Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs). Thus, all the pharmacy staff (38.4%) were well aware of COVID-19, with about 36.4% of the community aware of its available brands and their standard dosing (i.e., to be administered in two divided doses). Additionally, the individuals reported positive attitudes toward ADRs following COVID-19 vaccination.

The statistical significance (p-value = 0.001 for most variables) indicated strong associations between knowledge levels and professional participation.

3.3. Attitudes of Pharmacy Staff towards COVID-19 Vaccines

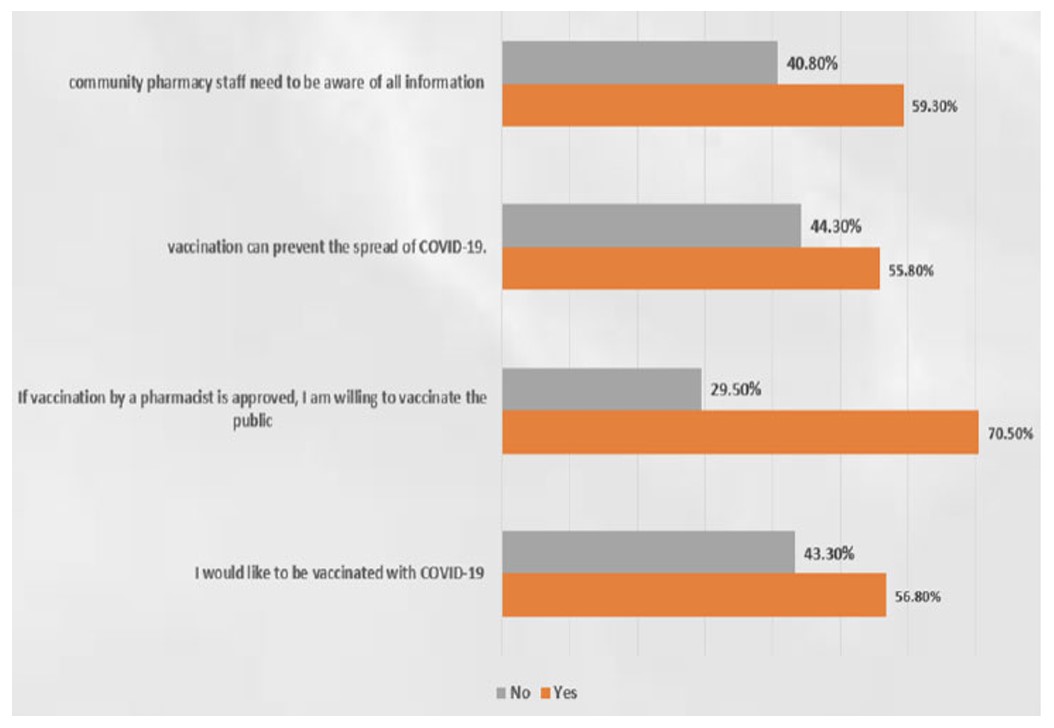

Attitudinal differences were evident across all the professional groups. Pharmacists exhibited the highest willingness to receive the vaccine and effective participation in community vaccination programs. Similarly, most pharmacists believed they should play an active role in vaccine administration, with a large proportion showing a positive response that vaccination helps prevent the spread of the virus (Table 2 and Fig. 3). The current findings were consistent with those of certain other related studies [28]. There was unanimous agreement among all groups that pharmacy staff need comprehensive information on COVID-19 vaccination.

| Indicator |

|---|

| Are you willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccination? |

| Pharmacist (56.8%) |

| Pharmacy technicians and Dispenser (43.3%) |

| Willingness to participate in community vaccination |

| Pharmacist (59.30%) |

| Pharmacy technicians and Dispenser (40.70%) |

| Willingness of the pharmacist to vaccinate the public permitted |

| Pharmacist (70.50%) |

| Pharmacy technicians and Dispenser (29.50%) |

| The spread of COVID-19 can be prevented by vaccination. |

| Pharmacist (55.80%) |

| Pharmacy technicians and Dispenser (44.20%) |

| Vaccination can completely control COVID-19 infection. |

| Pharmacist (45.50%) |

| Pharmacy technicians (30.30%) |

| Dispenser (24.70%) |

| I think pharmacy staff need complete COVID-19 vaccination information. |

| Pharmacist (35.1%) |

| Pharmacy technicians (33.34%) |

| Dispenser (30.33%) |

Diagrammatic data representation of the attitude of pharmacy staff regarding COVID-19 vaccination.

3.4. Practices of Pharmacy Staff towards COVID-19

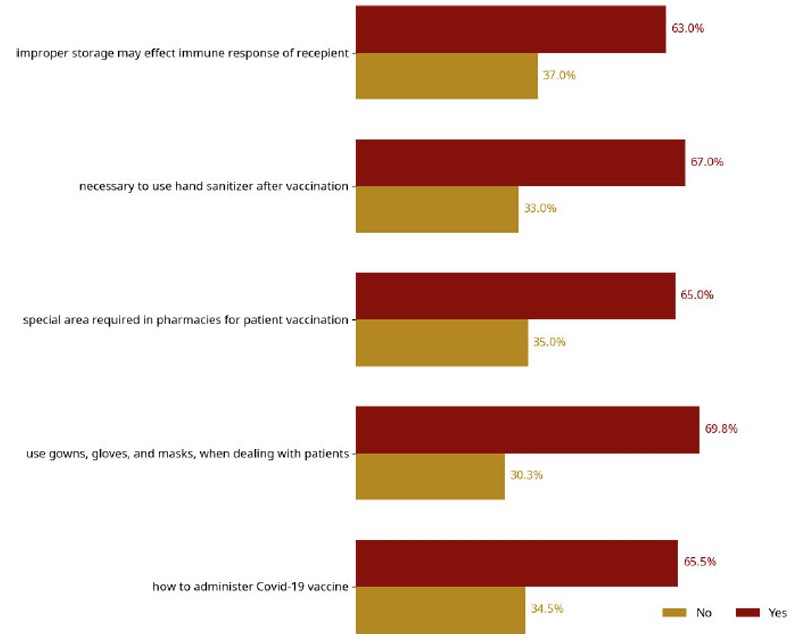

Practice-related information revealed gaps, particularly among dispensers. While 43.3% of pharmacists expressed readiness to receive the vaccine, only 15% of dispensers agreed. Knowledge of vaccine administration was also higher in pharmacists (40.8%) than in dispensers (21.8%). The proper use of protective equipment, including gloves, gowns, and masks) were reported by 38.7% of pharmacists and 26.5% of dispensers. Interestingly, most participants supported the idea of designated areas within pharmacies for vaccination and patient counseling (34.6%), though this was not statistically significant (p = 0.06). Improper vaccine storage was a concern for the majority, with 36.9% of pharmacists recognizing its impact on immune response. Hand sanitization after vaccination was also widely acknowledged, particularly among pharmacists (40.1%) (Table 3 and Fig. 4)

| Variables | Yes | No | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Are you willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccination? | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 99(43.8) | 25(14.4) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 93(41.2) | 52(29.9) | |

| Dispenser | 34(15) | 97(55.7) | |

| Do you know how to administer the COVID-19 vaccine? | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 107(40.8) | 17(12.3) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 98(37.4) | 47(34.1) | |

| Dispenser | 57(21.8) | 74(53.6) | |

| Gowns, gloves, and masks must be used while interacting with COVID-19 patients. | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 108(38.7) | 16(13.2) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 97(34.8) | 48(39.7) | |

| Dispenser | 74(26.5) | 57(47.1) | |

| Do you think a special area is required in pharmacies for patient vaccination and counseling? | 0.06 | ||

| Pharmacist | 90(34.6) | 34(24.3) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 80(30.8) | 65(46.4) | |

| Dispenser | 90(34.6) | 41(29.3) | |

| The immune response of the vaccine recipient may be affected by improper storage of COVID-19 vaccines. | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 99(36.9) | 25(18.9) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 82(30.6) | 63(47.7) | |

| Dispenser | 87(32.5) | 44(33.3) | |

| Is it necessary to use hand sanitizer after vaccination? | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 101(40.1) | 23(15.5) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 81(32.1) | 64(43.2) | |

| Dispenser | 70(27.8) | 61(41.2) | |

A figure representing the ongoing practices of pharmacy staff towards COVID-19.

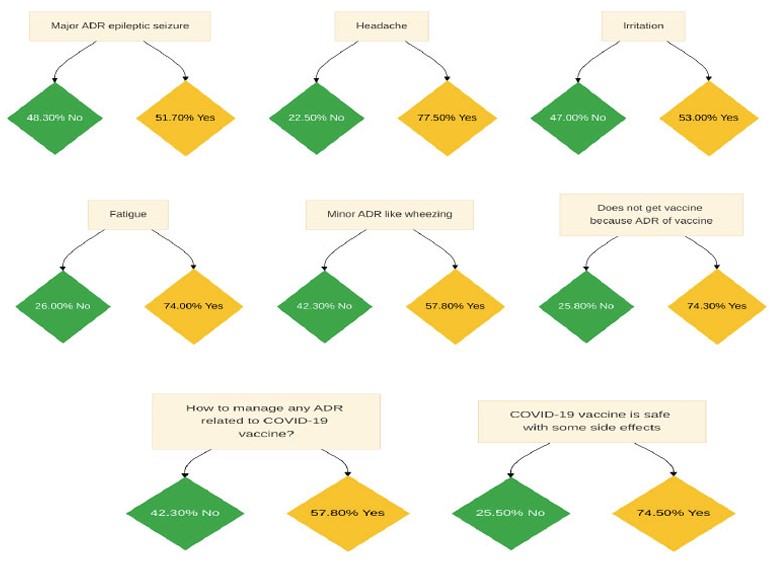

3.5. Phase II Adverse Events related to Vaccines (COVID-19)

Awareness regarding adverse events varied accordingly. Pharmacists were most aware of vaccine-related side effects such as lip/throat swelling (37%), wheezing (36.8%), and shortness of breath (35.7%) (Table 4A, 4B & Fig. 5). Knowledge regarding more severe symptoms, including seizures and fatigue, was lower across all groups, with no significant statistical differences observed among some cases (e.g., seizures, p-value = 0.94) (Table 4A, 4B and Fig. 5).

| Table (4A) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Yes | No | P-value |

| What do you think about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine? | 0.12 | ||

| Pharmacist | 100(35.5) | 24(20.3) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 96(34) | 49(41.5) | |

| Dispenser | 86(30.5) | 45(38.1) | |

| Do you know any adverse events related to the COVID-19 vaccine? | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 106(35.6) | 18(17.6) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 103(34.6) | 42(41.2) | |

| Dispenser | 89(29.9) | 42(41.2) | |

| Wheezing side effects | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 85(36.8) | 39(23.1) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 65(28.1) | 80(47.3) | |

| Dispenser | 81(35.1) | 50(29.6) | |

| Swelling of the lips, face, and throat | 0.02 | ||

| Pharmacist | 95(37) | 29(20.3) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 87(33.9) | 58(40.6) | |

| Dispenser | 75(29.2) | 56(39.2) | |

| Epileptic seizure | 0.94 | ||

| Pharmacist | 74(35.7) | 50(25.9) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 68(32.9) | 77(39.9) | |

| Dispenser | 65(31.4) | 66(34.2) | |

| Fatigue | 0.45 | ||

| Pharmacist | 97(32.8) | 29(27.9) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 95(32.1) | 48(46.2) | |

| Dispenser | 104(35.1) | 27(26) | |

| Injection size reactions | 0.39 | ||

| Pharmacist | 89(33.1) | 35(26.7) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 86(32) | 59(45) | |

| Dispenser | 94(34.9) | 37(28.2) | |

| Table (4B) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Yes | No | P-value |

| Irritation | 0.14 | ||

| Pharmacist | 74(34.9) | 50(26.6) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 69(32.5) | 76(40.4) | |

| Dispenser | 69(32.5) | 62(33) | |

| Headache | 0.01 | ||

| Pharmacist | 110(35.5) | 14(15.6) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 108(34.8) | 37(41.1) | |

| Dispenser | 92(29.7) | 39(43.3) | |

| Heart Burn | 0.18 | ||

| Pharmacist | 102(37) | 35(29.4) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 88(31.9) | 55(46.2) | |

| Dispenser | 86(31.2) | 29(24.4) | |

| Shortness of breath | 0.03 | ||

| Pharmacist | 96(35.7) | 33(25.2) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 82(30.5) | 63(48.1) | |

| Dispenser | 91(33.8) | 35(26.7) | |

| The patient does not get the vaccine because of fear of side effects | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 107(43.3) | 17(11.1) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 88(35.6) | 57(37.3) | |

| Dispenser | 52(21.1) | 79(51.6) | |

| Do you know how to manage ADR of the COVID-19 vaccine? | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 117(39.4) | 7(6.8) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 99(33.3) | 46(44.7) | |

| Dispenser | 81(27.3) | 50(48.5) | |

The belief that fear of side effects reduces vaccine uptake was most strongly observed by pharmacists (43.3%). Moreover, 39.4% of pharmacists also claimed that they know about how to manage vaccine-related ADRs when compared to dispensers (27.3%) (Table 4B and Fig. 5).

3.6. ADR Reporting of COVID-19 Vaccines

Pharmacists showed a significantly stronger commitment to ADR reporting. Nearly 40% agreed that reporting of ADRs is vital for ensuring vaccine safety. Educational background seemed to better prepare pharmacists (38.9%) as compared to dispensers (25.3%). The majority of pharmacists (39.8%) believed ADR reporting is a professional responsibility and observed themselves as critical healthcare players in this context (41%) (Table 5).

Support for institutional promotion of ADR reporting was highest among pharmacists (40.8%). However, only 42.1% cases reported maintained ADR records, and even fewer cases (41.8%) had been observed to report suspected ADRs to manufacturers/regulatory authorities, i.e., DRAP (Table 5).

Data interpretation of numerous ADRs reported during Phase II clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccination.

| Indicator | Yes | No | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| I believe that the adverse drug reaction ADR reporting is an important activity to improve the safety of vaccines. | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 88(39.1) | 36(20.6) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 78(34.7) | 67(38.3) | |

| Dispenser | 59(26.2) | 72(41.1) | |

| My educational background has provided me with enough information about the reporting of ADRs in Pakistan. | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 89(38.9) | 35(20.5) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 82(35.8) | 63(36.8) | |

| Dispenser | 58(25.3) | 73(42.7) | |

| Adverse Drug Reaction reporting is a professional responsibility. | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 103(39.8) | 21(14.9) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 91(35.1) | 54(38.3) | |

| Dispenser | 65(25.1) | 66(46.8) | |

| I consider myself an important healthcare worker for reporting an ADR. | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 100(41) | 23(14.8) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 81(33.2) | 64(41.3) | |

| Dispenser | 63(25.8) | 68(43.9) | |

| Reporting an ADR should be promoted in the workplace. | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 109(40.8) | 17(13.7) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 98(34.2) | 45(36.3) | |

| Dispenser | 69(25) | 62(50) | |

| Do you keep records of ADR? | 0.19 | ||

| Pharmacist | 112(42.1) | 22(24.7) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 94(24.8) | 39(43.8) | |

| Dispenser | 103(33.1) | 28(31.5) | |

| Have you reported suspected ADR to the manufacturer or DRAP? | 0.001 | ||

| Pharmacist | 74(41.8) | 50(22.4) | |

| Pharmacy technicians | 59(33.3) | 86(38.6) | |

| Dispenser | 44(24.9) | 87(39) | |

3.7. Chi-Square Analysis

Statistical tests (Chi-square) confirmed significant associations (p < 0.05) among professional contribution and levels of knowledge, attitudes, practices, awareness of adverse effects, and willingness to report ADRs. Pharmacists consistently demonstrated stronger competencies in all categories, underscoring the importance of their role in the COVID-19 response.

4. DISCUSSION

This study is the first of its kind to assess the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) of community pharmacy staff in Pakistan regarding COVID-19 immunization. The findings reveal a growing role of pharmacy professionals in vaccine advocacy and delivery, contributing to an overall rise in vaccination rates.

A significant proportion of pharmacy staff (67.25%) demonstrated good knowledge and adherence to COVID-19 vaccination, with 70.25% accurately identifying dosage schedules. Notably, pharmacists showed higher awareness and willingness to be vaccinated compared to pharmacy technicians and dispensers. This suggests that pharmacists possess a more advanced understanding of the COVID-19 vaccine, a finding consistent with international studies. For example, a study conducted in Asia reported over 95% willingness among healthcare workers to be vaccinated [29]. Similarly, research from South and Southeast Asia showed high vaccine uptake due to pharmacists' belief in vaccine safety and the severity of the pandemic [14]. KAP studies indicated a better association among pharmacy professionals and COVID-19 vaccine knowledge practices. Positive attitudes (such as willingness to vaccinate) and practices like the use of PPE by 70% individuals correspond to and align with other studies conducted in Asian countries; however, the gap in the ADRs reporting system highlighted the need for professional training.

Comparable findings were reported in Vietnam, Lebanon, Egypt, and Pakistan, where pharmacists demonstrated strong vaccine-related knowledge, with rates ranging from 83% to over 90%. Conversely, lower awareness levels were observed in regions like Addis Ababa (53.2%) [30-33]. Overall, the purpose of vaccination was widely understood to protect individuals and their families, though some resistance stemmed from perceived lack of necessity.

More than 60% of pharmacy staff in our study were knowledgeable about vaccine brands and mechanisms of action, and had access to updated vaccine information. Pharmacists consistently outperformed other staff in vaccine-related knowledge, echoing the results of prior studies across Asia and Africa [5, 16, 34-37], which indicated high COVID-19 knowledge among pharmacists about vaccines.

When analyzing attitudes, over 60% of participants believed that COVID-19 could be fully controlled. Many expressed willingness to support community-level vaccination efforts and recognized the pharmacist’s role in preventing the spread of the virus. A large majority were in favor of empowering pharmacists to administer vaccines, provided regulatory approval was granted. These positive attitudes mirror findings from Vietnam and Egypt, where pharmacists showed strong alignment with national health strategies [6, 32]. Similarly, in another study between June and July 2020 in Egypt, pharmacists evaluated the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the Egyptian population. Pharmacists found that about 64% of participants showed positive attitudes towards the Egyptian Ministry of Health in controlling the pandemic, which was slightly higher than in our studies [18].

In terms of practical behavior, about 70% of pharmacy staff reported using Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) such as gowns, gloves, and masks when dealing with patients. Additionally, 65% felt that pharmacies should have designated areas for vaccination and patient counseling. Around 63% supported the use of hand sanitizers post-vaccination, and 67% understood the impact of improper vaccine storage on immune responses.

Our findings also highlight that pharmacists possessed more practical knowledge on vaccine administration than other pharmacy personnel. Similar outcomes were seen in a Polish study, where pharmacists played a key role in vaccine delivery during the pandemic [38].

Regarding Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs), 75% of participants believed that COVID-19 vaccines are generally safe, albeit with some side effects [37, 39]. Furthermore, 74% were confident in managing both minor and major adverse events, although 60% of respondents admitted that fear of side effects might deter vaccine uptake. These concerns are supported by prior findings indicating vaccine hesitancy due to fear of ADRs [19, 40]. Thus, regular training and education for pharmacy staff are essential to strengthening Pakistan’s pharmacovigilance system. Empowering pharmacy personnel with the tools and knowledge to recognize and report ADRs could lead to a more responsive and transparent vaccine safety infrastructure [40, 41].

This study further investigated the KAP of community pharmacy workers in terms of ADR reporting. In the current study, a 56.3% response rate was observed, whereas a higher response rate (82%) was observed in another study by Paul et al., 2020 [8]. A lower response rate (21.8%) was reported by other studies [10, 42]. The majority of participants had a positive view of pharmacovigilance. 61.2% of pharmacy staff thought it was important to report Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs) because of the importance of the pharmacovigilance program. The significant respondent (77.8%) kept records of ADR and forwarded the detailed report to the ADR reporting center. Similar findings were also reported in various studies, which showcase agreement with our results [18, 39]. Education and regular training for pharmacy employees may help in pharmacovigilance program success and build a spontaneous ADR reporting system in Pakistan [43, 44]. Current Associations suggest positive aptitude, like supporting vaccination efforts; however, alternative measures like unmeasured motivation or information access may create differences. Thus, residual confounders or possible bias are possible [8, 9].

5. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The results of the current study are restricted to twin cities in Pakistan and may not be applicable to other regions of the country; therefore, a similar study can be conducted in other regions to better understand the concept.

The scope of this study was geographically limited to community pharmacies located in the twin cities of Islamabad and Rawalpindi, Pakistan. As such, the findings may not be generalizable to other regions of the country due to potential differences in healthcare infrastructure, access, education, and professional practice standards. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of pharmacy staff's knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) nationwide, similar research should be conducted in other provinces and rural settings. Expanding the geographical scope would provide a more holistic view and support the development of region-specific policies and interventions.

CONCLUSION

The findings of the current study revealed that overall pharmacy staff have better knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 vaccines, and this could be because pharmacy workers had a rudimentary understanding of these services with basic training. However, there was a significant difference in pharmacist knowledge and preparedness as compared to other health care workers for immunization services in the community settings. This might be due to the fact that basic concepts of immunization are incorporated in the curriculum of pharmacy, so pharmacists have basic knowledge regarding immunization. In order to improve knowledge of other pharmacy staff, a number of changes are required, including updating the pharmacy curriculum taught, implementing international standards for pharmacy practice, training, and fully integrating pharmacy staff into the healthcare system. Furthermore, health care staff should dispel patients' concerns about COVID-19 vaccines. If any untoward adverse event occurs, the report must be submitted to the ADR reporting center. The results of the present study showed that improved knowledge will lead to better implementation of immunization services.

FUTURE RECOMMENDATIONS

Various factors in community pharmacy settings should be studied separately with the purpose of developing interventions for improving the knowledge, practice, and attitude of pharmacists.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: A.S.: Study conception and design; S.B.: Conceptualization; I.Z.: Methodology; I.A., H.O.: Data collection: S.A.K.: Analysis and interpretation of results; K.U., M.A., H.O.: Draft manuscript; and I.A.: revision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ADRs | = Adverse Drug Reactions |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

| KAP | = Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices |

| PPE | = Personal Protective Equipment |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Hamdard University, Islamabad (Approval Number: ERC-FOP-03-01)

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors and will be provided upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all community pharmacy personnel who participated in this study and Hamdard University (Islamabad), Comsats University Islamabad (Abbottabad campus), and the University of Lahore (Sargodha campus) for institutional support.