All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Policy-aligned Research Trajectories in AI-Enabled Clinical Trials: A 2015–2025 Bibliometric Synthesis and Governance Implications for Korea and the UK

Abstract

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a key driver of innovation in clinical research and public health. This study aimed to identify policy-aligned research trajectories in AI-enabled clinical trials in Korea and the United Kingdom from 2015 to 2025.

Methods

A bibliometric synthesis was conducted using the Web of Science Core Collection to analyze publication trends, research domains, and institutional networks. Policy alignment was assessed through qualitative mapping of national strategic documents from both countries, including Korea’s Ministry of Health and Welfare R&D Implementation Plans and the UK’s MRC and NIHR strategies.

Results

In this study, we analyzed 925 publications to examine trends in AI-enabled clinical trial research in Korea and the UK. Publication activity increased steadily in both countries. Korean studies most often applied AI to outcome analysis and data integration, whereas research from the UK covered a broader set of trial stages, including design, recruitment, and monitoring. We also observed differences in collaboration patterns, with Korean research activity concentrated in university hospitals and UK research distributed across NHS trusts and research institutes. When these findings were compared with national policy documents, both countries showed overlapping priorities related to digital health, real-world data use, and international research collaboration.

Discussion

Based on these results, we interpret the research landscapes of Korea and the UK as exhibiting complementary strengths in AI-enabled clinical trial research. Korea’s emphasis on outcome-oriented applications contrasts with the UK’s engagement across multiple trial stages. We view these differences as indicating areas where coordination could be explored, particularly in relation to interoperability, data sharing, and trial efficiency, without implying established governance outcomes.

Conclusion

By integrating bibliometric evidence with policy analysis, we provide a comparative overview of AI-enabled clinical trial research in Korea and the UK. We interpret the findings as a basis for informing future discussions among researchers and policymakers about collaborative governance approaches in this field, within the scope of the study’s methodological limitations.

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite substantial progress in biomedical science, clinical trials continue to face practical challenges, including high operational costs, extended timelines, and persistent difficulties in recruiting and retaining participants [1]. These constraints can delay the translation of new therapeutics and interventions into routine clinical practice and limit the scalability of conventional trial designs. In this context, researchers have increasingly examined digital technologies-particularly artificial intelligence (AI)-as tools to support specific stages of clinical trials, such as trial design, monitoring, and outcome analysis through data-driven methods [2,3]. In this study, we focus on how AI has been applied across different stages of the clinical trial process, noting that adoption remains uneven despite the broader expansion of AI applications in healthcare. This observation motivates a comparative analysis aimed at clarifying current research patterns and informing future collaborative efforts.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is now widely used across multiple areas of healthcare, including medical imaging, diagnostics, prognostics, and clinical decision support [4–6]. Prior systematic reviews and bibliometric analyses have documented a marked increase in AI-related publications since 2015, corresponding with advances in machine learning, deep learning, and natural language processing methods [7–9]. In several application areas, AI-based approaches have shown performance comparable to that of human experts, particularly in image interpretation, disease prediction, and risk stratification tasks [10–11]. However, bibliometric evidence also indicates that research activity has been unevenly distributed, with a strong concentration in imaging and diagnostic applications and relatively limited attention to translational research and clinical trial contexts [12]. This imbalance suggests that, despite rapid growth in healthcare AI research, the incorporation of AI across the clinical trial ecosystem remains at an early stage and merits closer examination at the national level.

Despite ongoing advances in healthcare AI, its application across the full clinical trial continuum remains uneven. Challenges related to trial design, patient recruitment, and retention continue to delay study timelines and increase costs, with prior reviews identifying recruitment difficulties as a leading cause of trial failure [13,14]. Although AI-based methods have been proposed to support functions such as trial design optimization, participant matching, and adaptive randomization, evidence demonstrating their effectiveness in routine trial settings is still limited [9]. Monitoring and follow-up also represent areas of slower adoption, as AI-enabled tools-including digital biomarkers and wearable devices-are largely confined to pilot studies and early-stage implementation [15,16]. Emerging use of real-world data (RWD) and decentralized trial models presents new opportunities for AI integration, but regulatory frameworks and evidentiary standards for these approaches continue to develop [17]. In parallel, international reporting guidelines such as CONSORT-AI and SPIRIT-AI have been introduced to improve transparency and reproducibility, yet their adoption across clinical trials has been variable [18,19]. Taken together, these considerations highlight the value of comparative analyses that combine bibliometric evidence with national research and policy contexts to better understand where AI-enabled clinical trials are progressing and where substantive gaps persist.

Korea and the UK offer useful comparative contexts for examining the development of AI-enabled clinical trials, as both countries have invested heavily in digital health and biomedical innovation while operating within distinct research systems. In Korea, national strategies have prioritized AI-based medical technologies and real-world data infrastructures, as reflected in the 2025 Ministry of Health and Welfare R&D Implementation Plan, with research activity largely centered in major academic hospitals and affiliated institutes [20]. By contrast, the UK has pursued a more distributed research model supported by the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), encompassing experimental medicine hubs, patient recruitment networks, and virtual ward initiatives [21,22]. In addition, both countries have expressed continued interest in international collaboration, including bilateral research efforts. Examining Korea and the UK together, therefore, helps illustrate how national policy priorities and institutional arrangements shape the adoption of AI in clinical trials, while providing a comparative basis for considering potential areas of cross-national cooperation.

This study examines AI-enabled clinical trial research in Korea and the United Kingdom by integrating bibliometric analysis with a review of national policy documents. The analysis focuses on four objectives: mapping publication trends over time, categorizing AI applications across key trial stages (design, recruitment, monitoring, and outcome analysis), examining institutional collaboration networks to identify central and bridging actors, and relating these patterns to national policy priorities. By combining quantitative bibliometric evidence with qualitative policy mapping, the study provides a comparative perspective on how AI has been incorporated into clinical trial research in each country and where gaps remain. This approach is intended to inform both scholarly discussions on AI in health research and policy-oriented considerations regarding future Korea–UK collaboration.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Data Sources

This study relied on the Web of Science Core Collection as the primary data source because of its standardized metadata structure, consistent journal indexing, and frequent use in international bibliometric comparisons. A topic-based search was conducted by combining AI-related terms with clinical trial–related terms: TS = (“artificial intelligence” OR “AI” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning”) AND TS = (“clinical trial*” OR “randomized” OR “phase I” OR “phase II” OR “phase III”). The search was limited to articles and reviews published in English between 2015 and 2025, with a data cutoff of June 30, 2025. Publications were retained if author affiliations included South Korea or the United Kingdom. Duplicate records were removed, and national outputs were calculated using a full-counting approach, whereby each publication was counted once per country. Bibliographic metadata, including full records and cited references, were exported in CSV format for subsequent analysis. The complete search strategy and preprocessing procedures are detailed in Supplementary Materials S1.

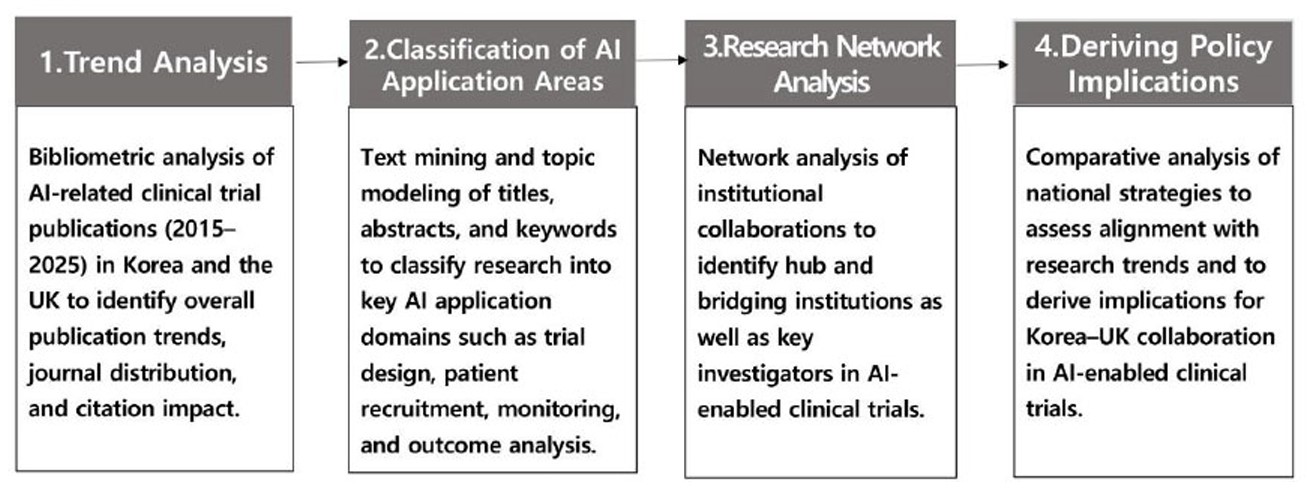

The analytical framework comprised four sequential components designed to examine publication trends, AI application areas, institutional collaboration networks, and policy alignment in AI-enabled clinical trials (Fig. 1). First, bibliometric trend analysis was conducted to capture annual publication outputs, journal distributions, and citation impacts in Korea and the UK. Second, text mining–based classification of article titles, abstracts, and keywords categorized publications into four major AI application domains: trial design, patient recruitment, monitoring, and outcome analysis. Third, institutional network analysis was performed to identify central and bridging organizations shaping collaborative research landscapes. Finally, the findings were mapped against national policy documents to derive strategic implications for Korea–UK cooperation in AI-related clinical trials.

Research framework for the analysis of AI-related clinical trial publications, including trend analysis, classification of application areas, institutional network analysis, and derivation of policy implications.

2.2. Trend Analysis

Annual trends of AI-related clinical trial research were examined using bibliometric data retrieved from the Web of Science Core Collection for South Korea (n = 215) and the United Kingdom (n = 710) between 2015 and 2025. Records were filtered to include English-language articles and reviews, and full counting was applied so that each publication was counted once per country. Three complementary analyses were performed: (i) annual publication counts by publication year to assess longitudinal growth, (ii) identification of the top 10 journals ranked by publication frequency, and (iii) listing of the top 10 most cited papers based on the “Times Cited” field, including bibliographic details and DOIs. Detailed parameters and outputs are provided in the Supplementary Materials (S2-1 for annual trends, S2-2 for top journals, and S2-3 for top-cited papers).

2.3. Classification of AI Application Areas

To classify AI application areas in clinical trials, we applied a rule-based text mining procedure to the article title, abstract, author keywords, and Keywords Plus fields. Each record was categorized into one or more of four predefined domains-trial design, patient recruitment, monitoring, and outcome analysis-based on regular-expression keyword matching. Multi-label assignments were allowed, and a predefined priority rule was used to determine the primary label when multiple domains were detected (Design > Recruitment > Monitoring > Outcome analysis). The complete regex-based keyword dictionary used for this classification is provided in Supplementary Material S3-1, along with human-readable keyword examples for transparency and reproducibility. To evaluate the methodological validity of the rule-based classification, we performed a validation procedure in which a randomly selected subset of records was manually annotated to create gold-standard labels and compared against the model’s predicted primary labels. The detailed validation metrics and confusion matrix outputs are presented in Supplementary Material S3-2. To formally assess whether the distribution of these primary application domains differed between countries, we conducted a chi-square test using Korea–UK primary label counts, and the detailed contingency table and test results are presented in Supplementary Materials S3-3.

2.4. Research Network Analysis

Institutional collaboration networks were constructed from author–affiliation information in the Korean (n = 215) and UK (n = 710) publication sets, using both “Authors with affiliations” and, when necessary, affiliation/address fields, with organization names normalized by abbreviation expansion, removal of department-level terms, and harmonization of variant forms of the same institution into a unified canonical label. Two institutions were connected if they co-occurred in the same paper, and edge weights reflected the number of co-occurrences, with only edges of weight ≥2 retained to reduce noise and to capture meaningful repeated collaborations rather than one-time co-authorship events. Centrality measures, including degree, weighted degree, betweenness centrality (approximated with k = 200 on the giant component), and eigenvector centrality, were calculated using the Brandes algorithm with k-approximation and the NetworkX `eigenvector_centrality_numpy` function (NumPy-based eigen-decomposition), respectively. Full edge lists and node metrics are provided in Supplementary Materials S4.

2.5. Deriving Policy Implications

To derive policy implications, national strategic documents were reviewed and mapped against the bibliometric findings. For Korea, the 2025 Ministry of Health and Welfare R&D Implementation Plan was analyzed, while for the UK, the Medical Research Council (MRC) strategic investment directions and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) annual report were examined. Key themes from these documents-such as digital health and AI-enabled clinical research, real-world data utilization, and international collaboration-were compared with the observed publication trends, application area distributions, and institutional network structures identified in this study. This triangulation allowed the alignment and gaps between research activity and policy priorities to be highlighted, providing a basis for formulating Korea–UK collaboration strategies in AI-enabled clinical trials.

2.6. Software and Reproducibility

All analyses were conducted in Python 3.12 (pandas 2.0.3; matplotlib 3.8.0); figure/table legends specify the data cutoff (June 30, 2025) and units, and step-level meta (files, filters, outputs) is provided in the Supplementary Excel file.

This study analyzed publicly available bibliographic records and national policy documents and did not involve human participants, identifiable personal data, or animals; therefore, formal ethics approval and informed consent were not required. Because no human participants were involved, participant consent was not required. The bibliometric records were retrieved from the Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate) under an institutional subscription and cannot be publicly redistributed. To ensure reproducibility, we provide a Supplementary Excel file containing the complete search strategy and preprocessing rules (S1), trend and citation outputs (S2-1 to S2-3), Rule-Based Classification dictionary and validation results (S3-1, S3-2), and institutional network node/edge lists with centrality measures (S4).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Trend Analysis Results

3.1.1. Annual Publication Trends (2015-2025)

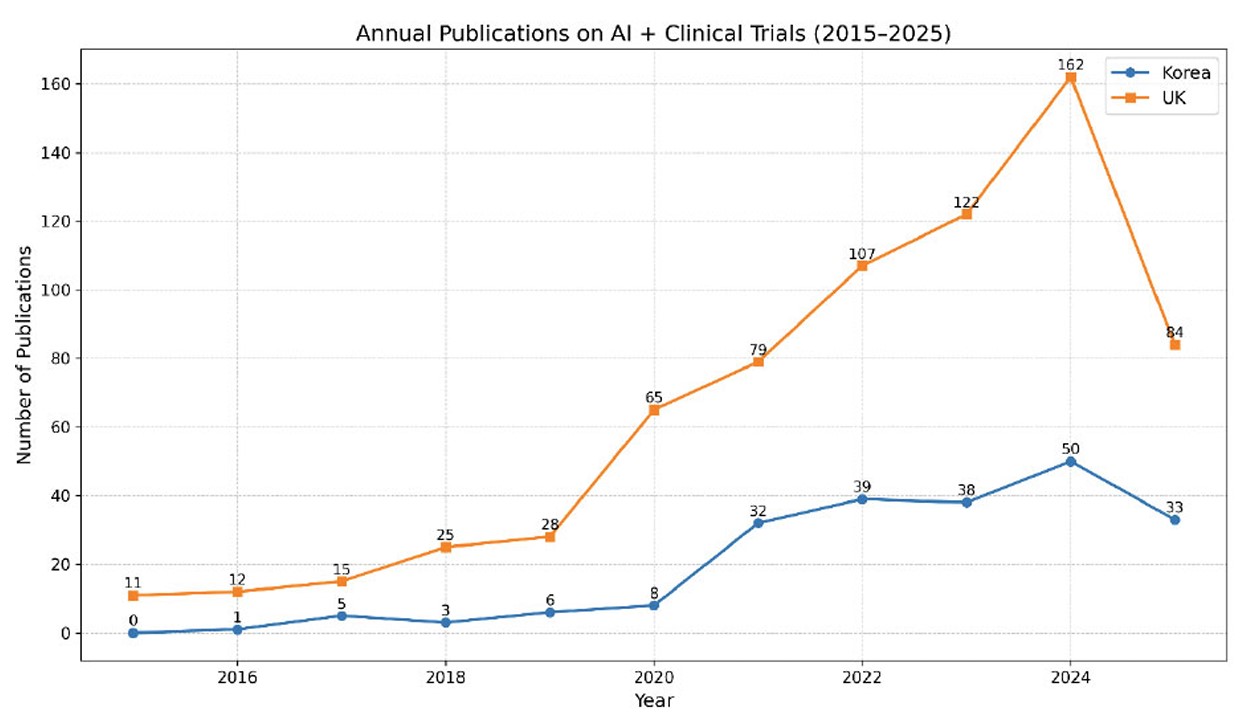

Between 2015 and 2025, the number of AI-related clinical trial publications increased markedly in both South Korea and the United Kingdom, with a steeper rise observed in the UK (Fig. 2). Korea showed a modest output until 2020, followed by steady growth that peaked in 2024 with 50 publications, before a slight decline in 2025, likely reflecting incomplete indexing for that year. In contrast, the UK demonstrated an earlier and sharper expansion, surpassing 100 publications by 2022 and reaching a peak of 162 in 2024. These results present annual publication counts without inferring differences in underlying research capacity or policy drivers.

3.1.2. Distribution of Top Journals

An examination of the most frequent publishing journals showed clear differences between Korea and the UK (Table 1). In Korea, AI-related clinical trial publications were spread across a range of journals, with IEEE Access and Scientific Reports each accounting for seven papers, followed by BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, NPJ Digital Medicine, and the Korean Journal of Radiology, each with five publications. In the UK, publications were more concentrated in a smaller number of widely recognized journals, led by Scientific Reports (n = 19) and BMJ Open (n = 17), and followed by Nature Medicine (n = 15), Nature Communications (n = 13), and The Lancet Digital Health (n = 12). Overall, these patterns indicate a more dispersed journal distribution for Korean studies and a greater concentration of UK studies in journals with broad international visibility.

3.1.3. Top Cited Papers

The most cited AI-related clinical trial papers differed between Korea and the UK (Table 2). In Korea, highly cited publications primarily addressed clinical imaging and algorithm performance, led by a Radiology article published in 2018 (643 citations) and a Lancet Neurology paper from 2023 (562 citations), with additional contributions appearing in the Korean Journal of Radiology and Scientific Reports. In contrast, UK publications accumulated higher citation counts overall and were more frequently published in journals with broad international reach, including Nature (2020, 1,884 citations) and Nature Reviews Drug Discovery (2019, 1,798 citations), followed by BMJ, Lancet Psychiatry, and The Lancet Digital Health. Taken together, these citation patterns reflect differences in the thematic focus and dissemination channels of highly cited work from the two countries.

Annual publication trends in AI-related clinical trials in Korea and the UK, 2015–2025. Note: Numbers are based on bibliometric analysis of the Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate Analytics). Publications include articles and reviews in English with author affiliations in South Korea or the United Kingdom. Data cutoff: June 30, 2025. Unit = papers.

| Journal | Korea (n) | Korea (%) | UK (n) | UK (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMC medical informatics and decision making | 5 | 2.33 | 0 | 0 |

| BMJ open | 0 | 0 | 17 | 2.39 |

| Cancers | 4 | 1.86 | 8 | 1.13 |

| CMC–computers materials & continua | 4 | 1.86 | 0 | 0 |

| Diagnostics | 4 | 1.86 | 0 | 0 |

| Ebiomedicine | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.99 |

| Experimental and molecular medicine | 4 | 1.86 | 0 | 0 |

| IEEE Access | 7 | 3.26 | 0 | 0 |

| IEEE Journal of biomedical and health informatics | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0.85 |

| International journal of molecular sciences | 4 | 1.86 | 0 | 0 |

| Journal of clinical medicine | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1.13 |

| Journal of medical internet research | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1.41 |

| Korean journal of radiology | 5 | 2.33 | 0 | 0 |

| Lancet digital health | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1.69 |

| Nature communications | 0 | 0 | 13 | 1.83 |

| Nature medicine | 0 | 0 | 15 | 2.11 |

| Npj digital medicine | 5 | 2.33 | 0 | 0 |

| Scientific reports | 7 | 3.26 | 19 | 2.68 |

Note: Numbers are based on bibliometric analysis of the Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate Analytics). Publication counts include articles and reviews in English with author affiliations in South Korea or the United Kingdom. Percentages represent each journal’s share of national publication output. Data cutoff: June 30, 2025. Unit = papers.

| Rank | Country | Paper Title | Journal | Year | Times Cited |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | UK | International evaluation of an AI system for breast cancer screening | Nature | 2020 | 1884 |

| 2 | UK | Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development | Nature reviews drug discovery | 2019 | 1798 |

| 3 | UK | Artificial intelligence versus clinicians: systematic review of design, reporting standards, and claims of deep learning studies | BMJ-British medical journal | 2020 | 731 |

| 4 | KR | Methodologic Guide for Evaluating Clinical Performance and Effect of Artificial Intelligence Technology for Medical Diagnosis and Prediction | Radiology | 2018 | 643 |

| 5 | UK | Anorexia nervosa: aetiology, assessment, and treatment | Lancet psychiatry | 2015 | 622 |

| 6 | UK | Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the CONSORT-AI extension | Lancet digital health | 2020 | 580 |

| 7 | KR | Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease-advances since 2013 | Lancet neurology | 2023 | 562 |

| 8 | UK | Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease-advances since 2013 | Lancet neurology | 2023 | 562 |

| 9 | UK | Guidelines for clinical trial protocols for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the SPIRIT-AI extension | Lancet digital health | 2020 | 489 |

| 10 | UK | Deep learning for prediction of colorectal cancer outcome: a discovery and validation study | Lancet | 2020 | 468 |

| 11 | UK | Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the CONSORT-AI extension | Nature medicine | 2020 | 438 |

| 12 | UK | Wearables in Medicine | Advanced materials | 2018 | 437 |

| 13 | KR | Design Characteristics of Studies Reporting the Performance of Artificial Intelligence Algorithms for Diagnostic Analysis of Medical Images: Results from Recently Published Papers | Korean journal of radiology | 2019 | 332 |

| 14 | KR | Predicting Alzheimer's disease progression using multi-modal deep learning approach | Scientific reports | 2019 | 305 |

| 15 | KR | HLPpred-Fuse: improved and robust prediction of hemolytic peptide and its activity by fusing multiple feature representation | Bioinformatics | 2020 | 174 |

| 16 | KR | A novel methodology for modal parameters identification of large smart structures using MUSIC, empirical wavelet transform, and Hilbert transform | Engineering structures | 2017 | 163 |

| 17 | KR | Recent advances in extracellular vesicles for therapeutic cargo delivery | Experimental and molecular medicine | 2024 | 143 |

| 18 | KR | Two-phase deep convolutional neural network for reducing class skewness in histopathological images based breast cancer detection | Computers in biology and medicine | 2017 | 128 |

| 19 | KR | Artificial Intelligence in Drug Toxicity Prediction: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives | Journal of chemical information and modeling | 2023 | 113 |

| 20 | KR | Update on benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | Journal of neurology | 2021 | 99 |

Note: Times cited values are based on citation counts (“Times Cited,” All Databases) from the Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate Analytics). Publications include English-language articles and reviews with author affiliations in South Korea or the United Kingdom. Data cutoff: June 30, 2025. Unit = papers.

3.2. Classification of AI Application Areas Results

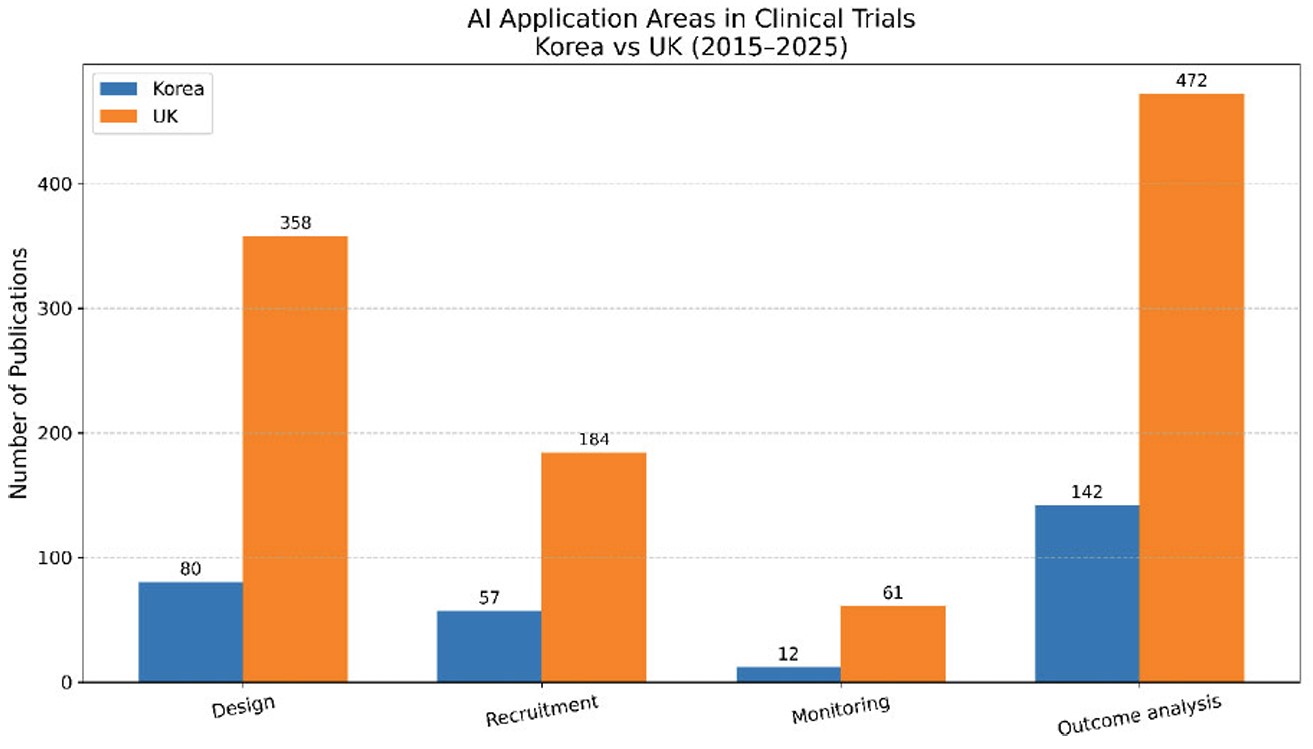

The distribution of AI application areas in clinical trial research revealed broadly similar patterns in Korea and the UK, with outcome analysis and trial design emerging as the dominant domains (Fig. 3). In Korea, outcome analysis accounted for the largest share (n = 142), followed by design (n = 80) and recruitment (n = 57), while monitoring was scarcely represented (n = 12). A comparable trend was observed in the UK, where outcome analysis (n = 472) and design (n = 358) led the field, with fewer studies addressing recruitment (n = 184) and monitoring (n = 61). In addition, validation of the rule-based classification procedure using manually annotated gold-standard labels yielded high performance, with a micro-average F1 score of 0.933 and a macro-average F1 score of 0.915 (Supplementary Materials S3-2). To compare application area distributions between the two countries, we conducted a chi-square test using primary label counts. The analysis indicated a statistically significant difference between Korea and the UK (χ2(3) = 17.06, p = 0.0007; Supplementary Materials S3-3. These findings summarize differences in domain-level publication patterns and are reported without attributing them to specific underlying motivations or research priorities.

3.3. Research Network Analysis Results

Institutional network analysis revealed different collaboration patterns in Korea and the UK (Tables 3and 4). In Korea, Seoul National University Hospital appeared as a central hub, together with research-focused institutions such as KIST, Yonsei University Health System, and KAIST. The Korean network exhibited relatively limited connectivity, comprising 104 institutions linked by 20 collaborative edges. By contrast, the UK network included a larger number of institutions (n = 330) and connections (70 edges), with several NHS foundation trusts-such as Moorfields, Oxford, Cambridge, and UCLH-functioning as key nodes, alongside international research organizations including INSERM and NICE. These findings describe patterns of institutional collaboration without attributing them to broader national research structures or strategies.

AI application areas in clinical trial publications in korea and the UK, 2015–2025. Note: Numbers are based on rule-based text mining of article titles, abstracts, author keywords, and Keywords Plus from the Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate Analytics). Publication counts include English-language articles and reviews with author affiliations in South Korea or the United Kingdom. Data cutoff: June 30, 2025. Unit = papers.

| Rank | Institution | Papers | Degree | Weighted Degree | Betweenness (GC) | Eigenvector (GC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seoul national university hospital | 23 | 6 | 15 | 0.66 | 0.57 |

| 2 | Korea institute of science & technology (KIST) | 9 | 4 | 11 | 0.29 | 0.31 |

| 3 | Yonsei university health system | 13 | 3 | 8 | 0.35 | 0.39 |

| 4 | Nih national cancer institute- of cancer epidemiology & genetics | 6 | 2 | 7 | 0.00 | 0.24 |

| 5 | Korea institute of radiological & medical sciences | 4 | 2 | 7 | 0.00 | 0.30 |

| 6 | Korea advanced institute of science & technology (KAIST) | 14 | 2 | 7 | 0.00 | 0.30 |

| 7 | Korea university medicine ku medicine | 14 | 3 | 6 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 8 | National cancer center - korea ncc | 8 | 2 | 5 | 0.08 | 0.16 |

| 9 | University of ulsan | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0.08 | 0.14 |

| 10 | Pusan national university hospital | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0.15 | 0.24 |

Note: Numbers are based on WoS bibliometric analysis conducted for 2015–2025 (South Korea: n = 215). Percentages not shown due to institutional-level analysis. Data cutoff: June 30, 2025. Unit = papers.

| Rank | Institution | Papers | Degree | Weighted Degree | Betweenness (GC) | Eigenvector (GC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Institut national de la sante et de la recherche medicale inserm | 74 | 20 | 61 | 0.64 | 0.46 |

| 2 | Moorfields eye hospital nhs foundation trust | 28 | 7 | 43 | 0.03 | 0.28 |

| 3 | University of california los angeles medical center | 25 | 7 | 40 | 0.00 | 0.33 |

| 4 | Royal liverpool & broadgreen university hospitals nhs trust | 24 | 7 | 39 | 0.04 | 0.29 |

| 5 | National institute for health & care excellence | 16 | 9 | 32 | 0.37 | 0.34 |

| 6 | Oxford university hospitals nhs foundation trust | 35 | 10 | 28 | 0.16 | 0.34 |

| 7 | University hospital birmingham nhs foundation trust | 12 | 6 | 22 | 0.00 | 0.29 |

| 8 | Cambridge university hospitals nhs foundation trust | 26 | 8 | 21 | 0.09 | 0.29 |

| 9 | University college london hospitals nhs foundation trust | 42 | 5 | 15 | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| 10 | University hospital southampton nhs foundation trust | 9 | 3 | 14 | 0.00 | 0.15 |

Note:Numbers are based on WoS bibliometric analysis conducted for 2015–2025 (United Kingdom: n = 710). Percentages not shown due to institutional-level analysis. Data cutoff: June 30, 2025. Unit = papers. INSERM and UCLA appear in the UK dataset due to frequent co-authorship with UK institutions in the WoS corpus.

| Clinical Trial Stage | WoS Bibliometric Results * | Korea (MOHW 2025 R&D plan) | UK (MRC/NIHR Strategic Priorities) | Mapping Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial design | Korea: 80 papers (≈37%); UK: 358 papers (≈34%) | Smart clinical trials, decentralized trials, digital therapeutics evaluation | MRC experimental medicine hubs; NIHR patient recruitment centers | Both countries emphasize innovation in trial design, particularly decentralized approaches, suggesting high potential for joint methodology development. |

| Recruitment | Korea: 57 papers (≈26%); UK: 184 papers (≈17%) | Investigator-initiated trials (IITs); hospital-based research networks | NIHR Clinical Research Networks; Patient Recruitment Centers (PRCs) | Collaborative opportunities exist to enhance patient recruitment efficiency through network integration. |

| Monitoring | Korea: 12 papers (≈6%); UK: 61 papers (≈6%) | Real-world data (RWD)–based monitoring; digital device validation | NIHR virtual wards; wearable/AI-enabled monitoring devices | Although underrepresented in publications, both countries are expanding policy support for AI-enabled monitoring, indicating strong potential for complementary collaboration. |

| Outcome analysis | Korea: 142 papers (≈66%); UK: 472 papers (≈44%) | AI-driven data analytics, prognostic and diagnostic algorithm support | NIHR AI Lab initiatives; large-scale cancer and diagnostic trials | Outcome analysis dominates the research output in both countries, aligning with policy priorities for data-driven medicine and offering a clear area for joint data and model sharing. |

Note: Numbers are based on WoS bibliometric analysis conducted for 2015–2025 (South Korea: n = 215; UK: n = 710). Percentages were calculated as proportions of total national outputs and rounded to the nearest whole number. Data cutoff: June 30, 2025. Unit = papers.

3.4. Policy Implication Results

Mapping the bibliometric findings to national policy documents indicated areas of alignment between research activity and strategic priorities in both Korea and the UK (Table 5). In both countries, outcome analysis and trial design accounted for the largest shares of research output, reflecting policy attention to AI-based data analysis, prognostic modeling, and decentralized clinical trial approaches. Although recruitment-related studies were fewer in number, they aligned with Korean policies supporting investigator-initiated trials and hospital-based research networks, as well as UK initiatives led by the NIHR Clinical Research Networks and Patient Recruitment Centers. Monitoring-related publications were least represented in the bibliometric data; however, both countries’ policy frameworks emphasize this area through initiatives involving real-world data infrastructures, virtual wards, and validation of AI-enabled monitoring tools. Overall, these patterns illustrate overlapping policy and research emphases across the clinical trial continuum, without implying definitive conclusions about bilateral collaboration outcomes.

4. DISCUSSION

This study offers a bibliometric overview of AI-enabled clinical trial research in Korea and the United Kingdom by integrating analyses of publication trends, application areas, institutional collaboration networks, and related policy documents. Over the past decade, publication activity increased in both countries, with the UK contributing a larger number of studies overall. Across both settings, AI applications were most frequently applied to outcome analysis and trial design, while recruitment and monitoring received comparatively less attention. Differences were also observed in collaboration patterns, with Korean research activity centered on a smaller number of major hospitals and UK research distributed across multiple NHS trusts and public research organizations. When considered alongside national policy documents, these bibliometric patterns point to areas of alignment between research activity and strategic priorities, while stopping short of indicating established or causal pathways for bilateral collaboration.

The patterns observed in this study are consistent with earlier reviews that have documented sustained growth in healthcare-related AI research and a strong focus on diagnostic and prognostic applications [23]. Previous bibliometric studies have likewise reported increasing volumes of AI-related publications since 2015, while noting that comparatively fewer analyses have addressed clinical trial contexts in detail [7,9]. Building on this literature, the present findings indicate that research activity in both Korea and the UK has been concentrated in outcome analysis and trial design, with recruitment and monitoring receiving less emphasis-an imbalance that has also been discussed in studies examining uneven adoption of digital technologies across the clinical trial process [24]. Differences in institutional collaboration patterns were also apparent, with Korean networks centered on a limited number of key institutions and UK collaborations spread across multiple NHS trusts and public agencies, echoing prior observations that national research environments influence collaborative structures [25]. By linking bibliometric evidence with national policy documents, this analysis adds a contextual layer to earlier descriptive work and provides preliminary insight into how research activity may correspond with strategic priorities, without implying direct causal relationships [25,26].

The integration of bibliometric findings with national policy documents points to areas of alignment between Korea and the UK in AI-enabled clinical trial research. In both countries, policy priorities emphasize outcome analysis and trial design, reflecting shared attention to data-driven prognostic approaches and decentralized trial models. Although recruitment and monitoring appear less frequently in the publication record, policy initiatives in both settings support investigator-led trials, hospital-based research networks, virtual wards, and the validation of wearable and AI-enabled monitoring tools. In interpreting these patterns, we consider that differences in institutional organization and research infrastructure may partly shape how AI is adopted across trial stages, rather than indicating established strategic impact or formalized bilateral governance pathways. Recent methodological developments in AI-enabled clinical trials, including the SPIRIT-AI and CONSORT-AI reporting extensions, further emphasize the importance of careful protocol design and transparent reporting practices in this area [9]. At the same time, observed differences between Korea and the UK across publication trends, application domains, and collaboration networks should be interpreted cautiously, as inferential statistical testing was limited to application domain distributions, and other comparative dimensions were examined descriptively due to data coverage and network structure constraints.

This study contributes to the literature by extending descriptive bibliometric analyses of healthcare AI through an integrated framework that links publication trends, application area classification, institutional collaboration networks, and national policy contexts. While earlier bibliometric work has largely emphasized global output volumes or specific technological applications without explicit reference to policy agendas [23], the present analysis offers a comparative perspective that situates research activity within strategic health R&D environments in Korea and the UK. The inclusion of institutional network analysis also draws attention to differences in collaboration structures that may influence research capacity, a dimension that has received limited attention in prior studies [9]. By adding policy mapping as a qualitative component, the study enhances the interpretability of bibliometric findings and provides context-based considerations, rather than prescriptive recommendations, for discussions on future collaboration in AI-enabled clinical trials.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the analysis was based exclusively on the Web of Science Core Collection; as a result, publications indexed only in other databases such as Scopus, PubMed, or ClinicalTrials.gov may not have been captured, particularly non-English or region-specific outputs. Second, the institutional network analysis relied on author affiliation data, which required normalization of organization names; despite systematic cleaning procedures, some degree of misclassification or aggregation of smaller institutions may remain. Third, although the rule-based classification achieved strong validation performance, it may be less sensitive to newly emerging terminology or contextual nuances not represented in the predefined keyword sets. Finally, the policy analysis focused on major national documents from Korea and the UK and therefore does not encompass the full range of funding mechanisms or regulatory initiatives. Taken together, these limitations indicate that the results should be interpreted cautiously and within the defined analytical scope, while still providing a coherent overview of observed research patterns.

Future studies could broaden bibliometric coverage by incorporating additional data sources such as Scopus, PubMed, and ClinicalTrials.gov to capture a wider range of AI-enabled clinical trial publications. Expanding comparative analyses to include more countries may also help clarify how variations in research environments and policy frameworks shape the adoption of AI in clinical trials. Methodological advances, including the application of machine learning–based natural language processing techniques, could further improve the flexibility and accuracy of application area classification beyond rule-based approaches. In parallel, closer integration of policy analysis with bibliometric evidence-such as linking research outputs to specific funding schemes, regulatory initiatives, and international collaboration programs-may support more nuanced assessments of AI-driven clinical research development at the global level.

CONCLUSION

This study presents an integrated bibliometric and policy-based examination of AI-enabled clinical trial research in Korea and the United Kingdom by combining analyses of publication trends, application areas, institutional collaboration networks, and national strategic documents. The findings indicate that outcome analysis and trial design account for a substantial share of research activity in both countries, while recruitment and monitoring remain less prominent in the literature despite growing policy attention. Differences in research organization-characterized by a more concentrated institutional structure in Korea and a more distributed network in the UK-suggest complementary strengths that may support future comparative learning rather than definitive evidence of established bilateral pathways. By situating quantitative bibliometric patterns within national policy contexts, this study offers preliminary insights that may inform ongoing discussions on collaborative approaches to AI-enabled clinical research. These conclusions should be interpreted within the scope of the study’s methodological limitations, including reliance on WoS data and the descriptive nature of the classification and network analyses.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: J.E.Y.: Study conception and design; A.R.K.: Draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OFABBREVIATIONS

| AI | = Artificial Intelligence |

| CONSORT-AI | = Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials-Artificial Intelligence extension |

| CSV | = Comma-Separated Values |

| DL | = Deep Learning |

| HER | = Electronic Health Record(s) |

| GC | = Giant Component |

| LCC | = Largest Connected Component |

| ML | = Machine Learning |

| MoHW | = Ministry of Health and Welfare (Korea) |

| MRC | = Medical Research Council (UK) |

| NHS | = National Health Service (UK) |

| NICE | = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| NIHR | = National Institute for Health and Care Research |

| RTA | = Relative Technological Advantage |

| RWD | = Real-World Data |

| SPIRIT-AI | = Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials-Artificial Intelligence extension |

| UK | = United Kingdom |

| WoS | = Web of Science Core Collection |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank all colleagues who provided constructive feedback and technical support during the preparation of this manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available on the publisher's website along with the published article.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

This file contains all supporting data and meta information used in the analysis:

- S1. Search strategy and preprocessing rules. Complete Web of Science query strings, filters (document type, language, timespan), and inclusion/exclusion criteria.

- S2-1. Annual trend analysis. Yearly publication counts for Korea and the UK (2015–2025).

- S2-2. Top journals. List of the top 10 journals by publication frequency in each country.

- S2-3. Top cited papers. Bibliographic details and citation counts of the 10 most cited papers per country.

- S3-1, S3-2, S3-3. Rule-Based Classification dictionary, validation results and Chi-square Test results.

- S4. Institutional network data. Node and edge lists, degree/weighted degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality metrics for Korea and the UK networks.