All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Strengthening Policy Implementation: A Practice Model for 72-Hour Assessments of Involuntary Mental Health Care Users

Abstract

Introduction

Despite challenges experienced during the 72-hour assessment of involuntary mental health care users, there is no practice model to strengthen the implementation of policy guidelines on such assessment in South Africa.

Methods

A qualitative, exploratory, descriptive, and contextual research design was followed. A practice model was developed from information obtained from mental health care practitioners and Mental Health Review Board members from three provinces in South Africa. The six crucial questions (agent, recipient, context, procedure, dynamics, and terminus) of Dickoff et al. were used to develop the model. An e-Delphi technique, aligned with Chinn and Krammer’s critical reflection questions, was followed using 21 mental health experts to validate the practice model.

Results

Consensus was reached, identifying the main themes of the model as follows: recipients, involuntary mental health care users and their families; agents, mental health care practitioners and heads of health establishments; process, training and development; stakeholders’ involvement, including recruitment and retention of competent staff, family and community engagement, and provision of designated 72-hour facilities. The dynamics encompass improved and adequate infrastructure, collaborative partnerships, and administrative support. The ultimate goal of the model is the proper implementation of the 72-hour policy guidelines.

Discussion

The practice model developed stipulates guidance to health professionals in 72-hour admission hospitals, indicating stakeholders and resources required.

Conclusion

This practice model provides sufficient information to health professionals for providing quality mental health care, treatment, and rehabilitation services to involuntary mental health care users.

1. INTRODUCTION

Globally, about 1 billion people suffer from mental illness [1]. Additionally, at least one person in every 40 dies by suicide, with approximately 450,000 people suffering from severe mental illnesses. According to Długosz and Liszka [2], 7 out of every 1000 households suffer from mental problems. In a 2019 meta-analysis, Wu et al. [1] estimated mental health conditions to be a common occurrence, affecting 22.1% worldwide. It is estimated that on average, 2% of South Africans suffer from severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, psychosis, and bipolar disorder, and that they affect approximately one in three persons in the country [3].

The burden of mental illness is pertinent across the world. For example, in Ontario, Canada, the Mental Health Act provides for a 72-hour assessment period during which individuals must be released, admitted willingly, or retained involuntarily with an authorization of involuntary admission [4]. In Scotland, the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 allows for emergency confinement for up to 72 hours, followed by short-term detention orders, which are subject to review by the Mental Health Tribunal for Scotland [5]. The Mental Health Act requires a 72-hour assessment period for involuntary mental health care users (MHCUs), during which medical practitioners examine the need for continuous treatment. This period is used to discern between mental health illnesses and other medical issues, ensuring proper care [6, 7]. However, regardless of the Mental Acts in place, challenges remain, such as limited bed availability, which results in patients being treated in general wards that may not provide effective mental health care [6, 8]. These problems increase the length of stay of MHCUs in hospitals. These international parallels highlight the need for a structured model to facilitate the execution and smooth implementation of the 72-hour assessment policy for involuntary MHCUs, including in South Africa. Exploring and learning from worldwide experiences demonstrates the need for the development of more effective and humane mental health treatment procedures, especially given the additional challenges.

The rise in unplanned hospital admissions and high mortality rates of MHCUs arise mostly from the involuntary MHCUs. These are individuals who present with unplanned mental health breakdowns and are admitted under involuntary mental health processes. Involuntary admissions of MHCUs are meant for individuals who cannot be included in decision-making related to their care [9, 10]. In relation to involuntary mental health admission, care, treatment, and rehabilitation, there is a concern regarding the implementation of the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs [11]. Some of the concerns are that the mental health care practitioners (MHCPs) are not specialists, and some lack an understanding of the relevant documents and procedures [10, 12, 13]. There are also issues related to facilities that are not designed to accommodate MHCUs for 72-hour assessments, a lack of human resources, an insufficient supply of medicine, and a lack of qualified healthcare providers [12, 14]. These are also limitations at most designated facilities that conduct 72-hour assessments, with ethical and moral concerns associated with implementing such assessments inherently connected to the violation of patients' rights [15, 16]

To maintain good standards of mental health, policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs are available to promote their care to prevent harm to self and others [17] and provide a set of instructions that must be followed to accomplish health care aims and objectives [18]. The instructions include procedures for clinical management regarding the assessment, treatment, care, and rehabilitation of involuntary MHCUs [17, 18]. Additionally, the 72-hour policy guidelines are intended to inform provincial heads of health about the conditions that must be met for facilities to conduct 72-hour assessments. However, there are no Practice Models (PMs) available to strengthen the implementation of the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs. It is for this reason that the researchers deemed it necessary to conduct this study. A PM refers to a system that includes a structure, process, and values which enable healthcare professionals to manage healthcare delivery, including the provision of care in a therapeutic and conducive environment [19, 20]. During the development and validation of a PM, teamwork and collaboration in professional relationships are vital [21]. Duffy and Faan [22] posited that a PM illustrates how health care providers work together, communicate, practice, and grow as professionals to give patients the best care possible. Furthermore, a PM shows how health care providers organise and deliver patient-centred care, attain the best possible outcomes for patients, and grow and function as professionals within their organization, and hence is vital. With increased unpleasant reports related to involuntary mental health care, researchers developed and validated a PM to strengthen the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in South Africa (SA).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Purpose of the Study

The objective of this study was to develop and validate a PM to strengthen the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in the North West, Gauteng, and Northern Cape Province (NCP) in South Africa.

2.2. Study Setting

The data in this study were collected from MHCPs [23] and the Mental Health Review Board (MHRB) members [24] from three provinces in SA, namely Gauteng Province (GP), North West, and the NCP. Data was collected from MHCPs working in 72-hour health facilities, as well as the MHRB members sourced from the respective provincial offices. The validation of the PM was carried out in the same provinces. The mental health experts (MHEs) included during the validation phase were based at mental health facilities and were medical doctors, psychiatric nurse specialists, and psychiatrists. There were other MHEs from the universities working as professors and lecturers with postgraduate psychiatric diplomas and Master’s degrees in psychiatric nursing. Other MHEs were recruited from the Department of Health (DoH) offices as clinical/mental health coordinators with specialization in psychiatry.

2.3. Study Designs

This manuscript is part of a PhD study which followed a qualitative exploratory-descriptive and contextual research design [23-25]. The research design allowed the researchers to collect in-depth information for the development and validation of a PM to strengthen the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs. The design was used in three phases: Phase 1 – empirical phase [23], Phase 2 –development phase [24], and Phase 3 – validation phase. The methodology of these phases is provided in the following sections.

2.3.1. Phase 1: Empirical Phase

Phase 1 had two steps.

In the first step, a non-probability sampling approach was used [23] to select 19 MHCPs (three males and 16 females), which included five medical doctors, nine professional nurses, one social worker, and four clinical psychologists. The demographic profile of the participants is provided in the supplementary material titled “Phase 1 Demographic Profile of Empirical Phase Participants [Mental Health Care Practitioners (MHCPs)].docx” [23]. The ages of the MHCPs ranged between 29 and 59 years. A quota sampling technique was used to select MHCPs per province, who were then purposively recruited in public facilities that render 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were used to collect data through Microsoft Teams, with three FGDs conducted in the three provinces of NWP, NCP, and GP. After data collection, Braun and Clark’s [26] six steps of thematic analysis were used to analyze data, which involved becoming acquainted with the data, producing codes, discovering themes, investigating the topics, recognizing themes, and compiling a summary of the findings. The researchers and the co-coder assessed the data independently and met on the Microsoft Teams platform to determine the final themes and sub-themes.

In the second step, 13 MHRB members were selected through a non-probability sampling approach [24]. FGDs using Microsoft Teams were used to collect data from all 13 MHRB members (females and males). The participants included three legal practitioners, four community members, and six professional nurses. The ages of the MHCPs ranged between 43 and 79 years. The demographic profile of the participants is provided in the supplementary material titled “Phase 2 Demographic characteristics of empirical phase participants [Mental Health Review Board (MHRB)].docx” [24]. Within the quota sampling technique, a predetermined number of potential participants was chosen non-randomly from the MHRB offices using a purposeful sampling technique. Data was analyzed through Clarke and Braun’s [26] six steps of data analysis. As in the first step of the empirical phase, the researcher and co-coder assessed the data independently and met on the Microsoft Teams platform to determine final themes and sub-themes.

2.3.2. Phase 2: Development Phase

This phase aimed at developing a PM for strengthening the implementation of the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs. The framework of Dickoff et al [27]. was used to develop the PM. The results of the empirical phase were used to develop a PM to strengthen the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA [23, 24]. The following six components of the Dickoff et al. framework [27] were adopted to develop the PM: agent, recipient, context, process, dynamic, and terminus.

In line with the findings of Dickoff et al. [27], the agents are the driving force that implement the PM toward a goal and have an effect as they actively participate. The recipient is defined as someone who receives and benefits from the activities of the PM to improve the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs. The context is the setting in which the PM is implemented. Dynamics refers to initiatives that ensure the success of the PM for the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA. The procedure refers to the actions taken to implement the PM. In this study, terminus refers to the outcome of the developed PM.

2.3.3. Phase 3: Validation Phase

The e-Delphi technique customized with Chinn and Krammer’s [28] critical questions was used to validate the PM. According to Nasa et al. [29], the e-Delphi technique is used to achieve consensus among “experts” as defined within the specific context of a study through several rounds to analyze expert viewpoints. The researcher used expert sampling techniques to select the MHEs for validation of a newly developed PM. These MHEs are well informed about the proper implementation of the recommendations for 72-hour assessment in relation to the PM. According to the Cambridge Dictionary [30], an expert is a person who exhibits an extensive level of knowledge or expertise in an area of expertise or activity. In all, 28 MHEs were recruited, although only 21 participated in this study. The ages of the MHEs ranged between 30 and 58 years. The researcher customized the critical reflection questions proposed by Chinn and Kramer [28] to suit the characteristics of e-Delphi as the third phase of a primary PhD study on the validation of a PM to strengthen implementation of the policy guidelines for the 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA. According to Nasa et al. [29] as well as Gause, Sehularo, and Matsipane [31], the e-Delphi technique is used to achieve consensus among “experts” as defined within the specific context of a study, through multiple rounds of analysis of expert viewpoints. In this study, the researchers followed a qualitative e-Delphi research approach where expert consensus was characterized as a meaningful agreement of inputs and ideas across participants throughout e-Delphi rounds. It was qualitatively quantified through analyzing the recurrence and stability of similar input, as well as the consistency of expert responses, frequently supported by agreement and participant confirmation from expert feedback [29, 31]. Chinn and Kramer’s [28] critical questions addressed whether the PM is clear, simple, can be generalized, is accessible, and is important. The tool comprised five closed-ended questions and one open-ended question Table 1 using a Likert scale to indicate a suitable rating (1=Strongly Disagree; 2=Disagree; 3=Neutral; 4=Agree; 5=Strongly Agree).

| Principles | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Comment(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | ||

| Clarity – Is the practice model clear? | ||||||

| Simplicity – Is the practice model simple? | ||||||

| Generalisability – Can the practice model be generalized? | ||||||

| Accessibility – Is the practice model accessible? | ||||||

| Importance – Is the practice model important? |

The same tool was used throughout all e-Delphi rounds, with adjustments to the model in relation to the MHEs’ comments and suggestions. The researcher started the first round of e-Delphi on 3rd April, 2024, with the second round starting on 16th May, 2024, and model validation for the third round starting on 11th June, 2024. Each MHE was given a two- to three-week period to complete documents for every e-Delphi round.

2.4. Participant Recruitment

A total of 32 participants took part in the empirical phase of the study, 19 MHCPs (step 1) and 13 MHRB members (step 2), recruited from three provinces of SA [23, 24]. MHCPs and MHRB members deemed unavoidably absent, on leave, or who declined to participate were excluded. The 19 MHCPs who took part included 9 professional nurses, one social worker, 5 medical doctors, and 4 clinical psychologists [23]. For the empirical phase step 2, the 13 MHRB members included 6 professional nurses, 4 community members, and 3 legal practitioners [24]. Consent was obtained from all participants to make recordings using Microsoft Teams after the researcher thoroughly explained the study. The participants signed consent forms, facilitated by a mental health specialist working as a senior lecturer (Doctor of Philosophy) at North-West University (NWU). The independent person ensured that participants were aware of the benefits and possible risks involved during data collection, in order to make an informed decision. To validate the PM, the researcher recruited 21 MHEs, who were involved throughout the e-Delphi process, purposively selecting them from among the psychiatric and 72-hour assessment hospital managers and universities/colleges in the three provinces. The researcher selected MHEs who are knowledgeable about how to properly implement the guidelines for the 72-hour assessment with respect to the PM. Characteristics and demographic details of the MHEs are listed in Table 2.

| No. | Employer | Occupation | Age (years) | Gender | Professional qualifications (highest qualification) | Years of experience in the health sciences/mental health care service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | DoH, North West | Advanced Psychiatric Nurse | 53 | Female | Master’s in Advanced Mental Health Care Nursing | 16 |

| 2. | DoH, Northern Cape | Medical Officer | 58 | Female | MBChB | 31 |

| 3. | DoH, Gauteng | Advanced Psychiatric Nurse | 55 | Female | Master’s in Advanced Mental Health Care Nursing | 20 |

| 4. | DoH, Northern Cape | Medical Officer | 31 | Female | MBChB | 5 |

| 5. | DoH, Gauteng | Psychiatric Nurse Specialist | 30 | Male | Postgraduate Diploma in Mental Health | 9 |

| 6. | DoH, North West | Specialist Mental Health Nurse | 30 | Male | Postgraduate Diploma in Mental Health | 5 |

| 7. | DoH, North West | Medical Officer | 38 | Female | MBChB | 14 |

| 8. | DoH, Northern Cape | Medical Officer | 49 | Male | MBChB | 19 |

| 9. | University, Gauteng | Lecturer | 52 | Female | Doctor of Philosophy in Health Science | 28 |

| 10. | University, Gauteng | Lecturer | 47 | Female | Doctor of Philosophy in Health Science | 14 |

| 11. | DoH, Northern Cape | Medical Officer | 40 | Male | MBChB | 9 |

| 12. | DoH, Gauteng | Clinical Programme Coordinator |

41 | Female | Postgraduate Diploma in Mental Health | 17 |

| 13. | DoH, Gauteng | Advanced Psychiatric Nurse | 41 | Female | Master’s in Advanced Mental Health Care Nursing | 9 |

| 14. | DoH, North West | Senior Manager Medical Service | 47 | Male | MBChB | 21 |

| 15. | DoH, North West | Mental Health Coordinator | 49 | Male | Master’s in Advanced Mental Health Care Nursing | 8 |

| 16. | University, North West | Professor | 51 | Female | Doctor of Philosophy in Health Science | 29 |

| 17. | DoH, Gauteng | Advanced Psychiatric Nurse | 33 | Female | Master’s in Advanced Psychiatric Nursing | 09 |

| 18. | DoH, North West | Acting Deputy Director of Nursing | 47 | Male | Master’s in Advanced Mental Health Care Nursing | 17 |

| 19. | DoH, North West | Psychiatrist | 41 | Female | MMed (Psych), FC (Psych) | 11 |

| 20. | DoH, North West + Private Sector | Medical Specialist (Psychiatrist) | 43 | Male | MMed (Psych), FC (Psych) | 13 |

| 21. | DoH, North West + Private Sector | Specialist Psychiatrist | 65 | Male | MMed (Psych), FC (Psych), | 37 |

2.5. Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness in the study’s empirical phase was ensured through credibility, confirmability, and transferability [23-25]. Credibility was ensured by maintaining prolonged engagement in the empirical and development phase, including the e-Delphi technique, through validating the PM with MHEs. Dependability and authenticity were achieved through peer examination and the involvement of a co-coder during data analysis. Confirmability was ensured through audio-recording the virtual semi-structured FGDs, and developing and validating the PM under the supervision of supervisors who were MHEs in the development and validation of models. Transferability was ensured through detailed descriptions of methods and results.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results of the study are presented and discussed according to the empirical and development phases.

3.1. Converging Results of the Empirical Phase

The FGDs with MHCPs and MHRB members aimed to ascertain their understanding of the current practice regarding implementation of the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA.

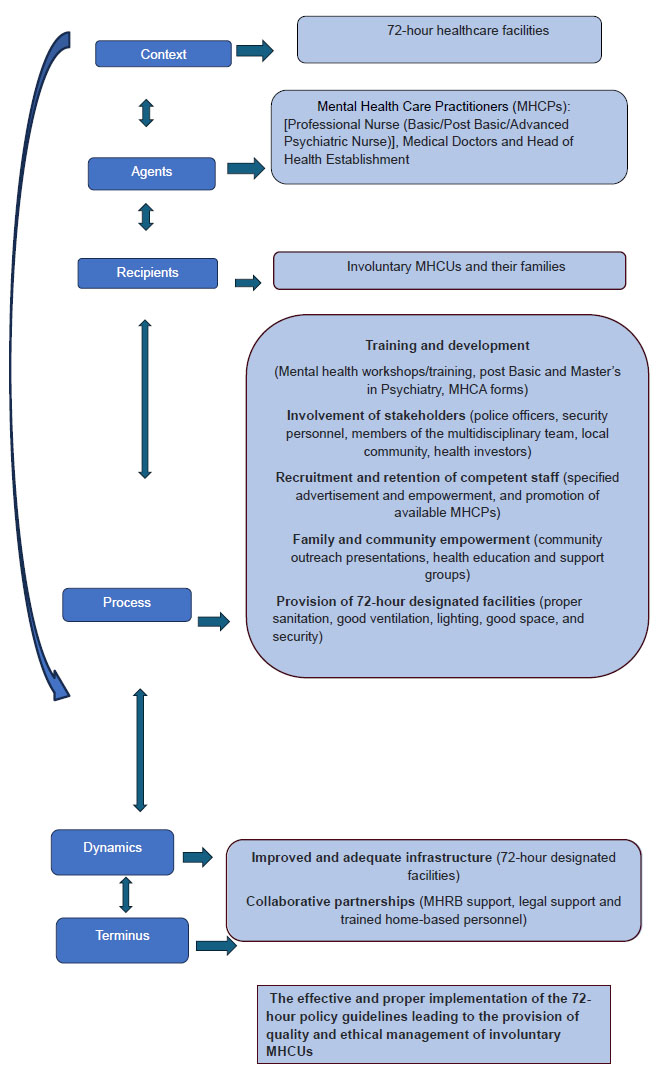

Three themes were derived from step 1: MHCPs' understanding of the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs; MHCPs' challenges with the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs; and MHCPs' suggestions to strengthen the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs [23]. In the empirical phase, step 2, three themes were derived: MHRB members’ understanding of the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs; challenges experienced by MHRB members when implementing the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs; and suggestions to strengthen the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs [24]. The results from the MHCPs’ and MHRB members’ inputs were used to develop the PM, as described by Mpheng et al. [23, 24]. Fig. (1) provides a structural component that includes the classification of components for a PM, using the framework of Dickoff et al. [27].

3.2. Relevance and Objectives of the PM

The implementation of the 72-hour policy guidelines was not addressed in a review of mental health policy guidelines; however, Memish et al. [32] shared that individuals who use the recommendations require support, including in-depth training. Additionally, as indicated in the introduction, since the 72-hour policy guideline is not implemented properly, there is a need for the development of a PM to strengthen the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs [32]. The PM is necessary, as indicated by the MHEs who expressed that recruitment and retention of knowledgeable MHCPs, including their continuous training and development, would ensure quality care towards the 72-hour assessment [23, 24]. Equally important are the collaboration of partnerships, administrative support, involvement of stakeholders, and family and community empowerment.

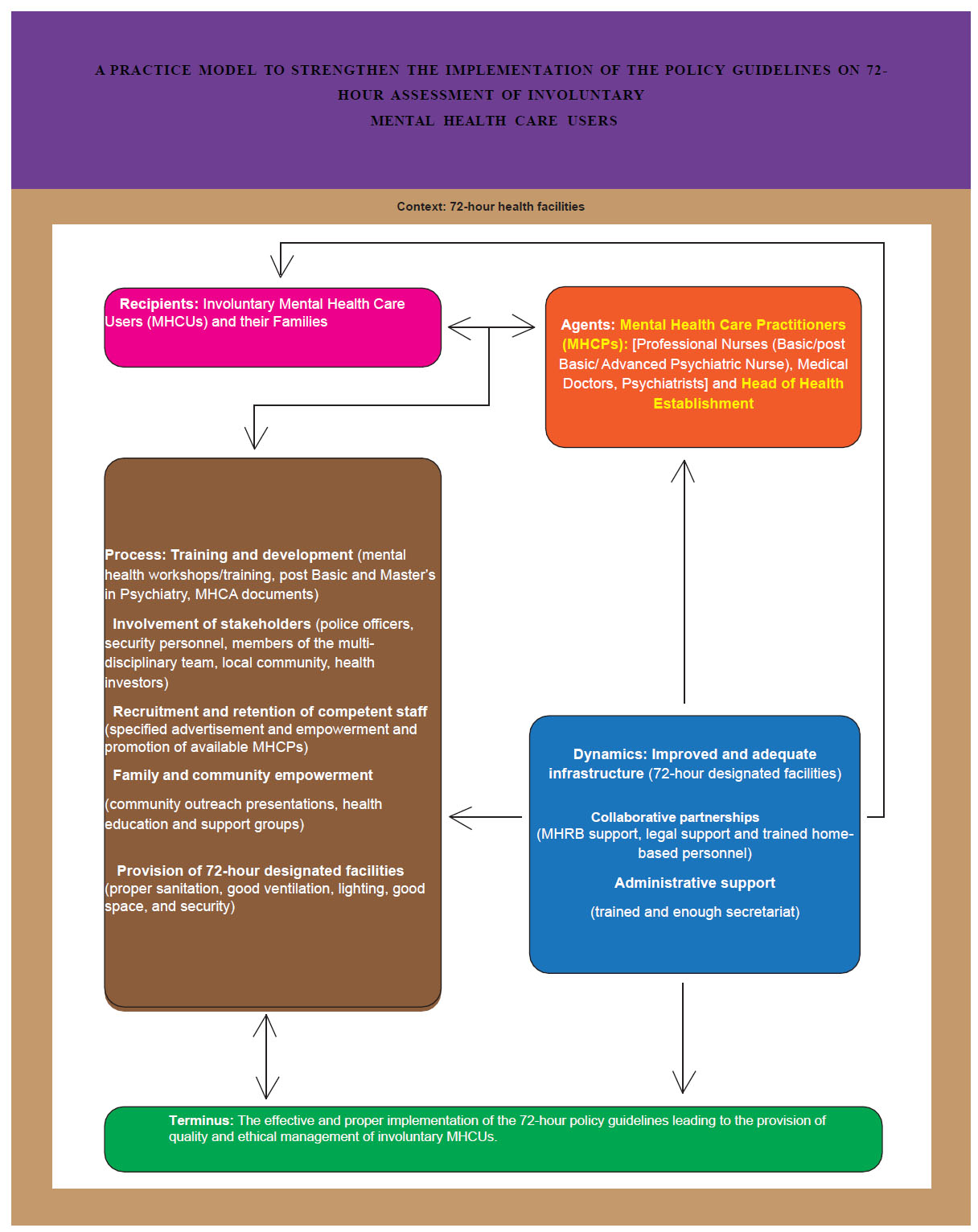

The PM could enable the MHCPs to render quality involuntary care in the mental health care institutions of SA, through strengthening the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessments of involuntary MHCUs [23, 24]. Furthermore, support from government officials is needed to prioritize the elements listed in the PM that may help to increase the effectiveness, safety, and quality of healthcare. The PM can also benefit the 72-hour assessment facilities and policymakers by supporting them in rendering quality health care. The researchers and the MHEs are certain that effective and proper implementation of the 72-hour policy guidelines through the PM will lead to the provision of quality and ethical management of involuntary MHCUs [23, 24]. Fig. (2) presents a practice model to strengthen the implementation policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in South Africa.

Classification of Concepts

A practice model to strengthen the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary mental health care users in South Africa (Adapted from Dickoff et al. (1968)).

3.3. Description of the Structural Presentation of the PM

3.3.1. Agents: Who is the Agent of the PM?

According to Dickoff et al. [27], an agent is a person who performs an activity. The term agents in this study refers to individuals who strengthen the implementation of a PM for policy guidelines on the 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA. The MHCPs and Head of Health Establishments (HHEs) of the hospitals are agents who are responsible for implementing the PM. The MHCA [17] defines MHCP as mental health professionals who have received the necessary training and are qualified to offer mental health care in SA. The agents of the PM include the MHCPs, who are regarded as professional nurses who have basic/post-basic and advanced psychiatric training, including medical doctors.

The HHE is regarded as a person who oversees a health care facility, called the chief executive officer of the facility [27]. The HHE is responsible for deciding whether the MHCU must be treated as an inpatient for the 72-hour assessment or an outpatient receiving care from home and should give notice to the applicant using MHCA 07 [17]. These agents have a direct impact on the mental health of the involuntary MHCUs during the 72-hour assessment [23, 24]. The MHCPs of this study and the HHEs must ensure that the involuntary MHCUs are well cared for during their 72-hour assessment and ensure that they are cared for and advocated for during their stay in the facility, while also promoting the continuation of care into the community [13, 23, 24].

3.3.2. Recipients: Who is the Recipient of the PM?

A person who receives the activity from the agent is referred to as the recipient [27]. The term recipients in this study refers to individuals who directly benefit from the proper implementation of the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA. The recipients of the newly developed PM for strengthening the implementation of policy guidelines on the 72-hour assessment of involuntary mental health care facilities in SA will be the involuntary MHCUs and their family members. The recipients will enjoy the benefits related to proper implementation of the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment when they are ethically respected and correct processes are followed from when the MHCU is admitted into a designated hospital, with proper filling in of MHCA forms, being treated by trained and skilled MHCPs, and so on. With consideration of their limitations to individual autonomy and the involuntary MHCUs’ choice to refuse treatment, the MHCA [17] gives authority and ethical obligation to the MHCPs to treat involuntary MHCUs without their consent [33, 34].

Additionally, involuntary mental health care is legalised as it provides 72-hour psychiatric detention for evaluation under involuntary care [23, 24]. Care of the involuntary MHCUs is given following the fact that the MHCU is incapable of making their own decision as they are a danger to themselves, and those around them, including the property [23, 24, 35]. Although the 72-hour policy guidelines were developed specifically for involuntary MHCUs who are the recipients of the PM, the family needs to participate during admission of the MHCU and to provide continuous support during rehabilitation and after discharge of the MHCU from the hospital. The involuntary MHCUs and their families require sufficient advocacy from the MHCPs and the HHEs to ensure that implementation of the 72-hour policy guidelines is carried out properly.

3.3.3. Context: In which Context will the PM be Implemented?

Dickoff et al. [27] defined context as the environment in which the activity will be implemented. In this study, context refers to the environment in which a PM for the implementation of the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA will be implemented. Involuntary admissions must occur in designated 72-hour health facilities, as outlined below under the process [23, 24]. The newly developed and validated PM will be implemented in health facilities that are accredited, meaning designated to provide 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs. The PM will be implemented within this context by the agent and received by the recipient, that is, the involuntary MHCUs.

As outlined by the MHCA [17], the facility must have the capacity to accommodate involuntary MHCUs who present with dangerous behaviour, mostly physically towards themselves or other people around them. The facility must be conducive for involuntary MHCUs as they might cause harm to themselves and those around them, including their surroundings, and the facility must include appropriate seclusion rooms [23, 24, 36].

3.3.4. Process: How will the PM be Implemented?

The process in the PM involves measures adopted in the implementation of the policy guideline on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA. The process used in this study presents a thorough explanation of how to execute activities effectively and protect the other five components, namely the agent, recipient, context, dynamics, and the terminus [27]. The activities are aimed at proper implementation of the 72-hour policy guidelines, with an accessible quality mental health service through provision of 72-hour designated facilities, while considering training and development, recruitment and retention of competent staff, family and community, empowerment and involvement of stakeholders [23, 24, 37]. The activities of the newly developed model are discussed below:

3.3.4.1. Training and Development

This study established that training and development of MHCPs who provide involuntary mental health services to MHCUs are important. Aktar [38] defined training and development as a strategy or technique for increasing the staff's knowledge, skills, and abilities to capacitate them to cope better with the ever-changing working environment and uncertain working conditions. Furthermore, this study advocates for training and development because this improves mental health service delivery through empowering the MHCPs with adequate skills and knowledge, as supported by Müller et al., Muddle et al., and Parniawski et al. [37, 39, 40]. According to the findings of this study, everyone involved in the admission, care, treatment, and rehabilitation of the involuntary MHCUs should be trained to ensure proper facilitation from admission and care [23, 24]. Similarly, the participants in this study agreed that by recruiting and retaining competent staff, incorrect implementation of the policy guidelines will be reduced or eliminated. Recruitment and retention of staff is the ability to attract and retain knowledgeable staff for improvement and ensuring quality mental health services [41, 42]. Furthermore, Bilan et al. [42] concurred that recruitment and retention of competent staff further improve service delivery, as MHCPs who have acquired necessary training and knowledge must be recruited and retained as qualified and competent staff.

Considering that mental health constantly evolves due to new advancements in healthcare and approaches to caring for different MHCUs, MHCPs should frequently acquire training and development to maintain quality mental health services [23, 24, 40]. It was also mentioned that MHCPs’ leadership development and expansion planning still need improvement through in-service training and qualification courses. In addition to professional advice based on the MHCPs’ experiences and perspectives, mental health leaders must offer training and development programmes [23, 24]. These programmes will support the empowerment of the MHCPs and promotion of high-quality service delivery, ensuring retention of available staff within a conducive environment [43].

3.3.4.2. Stakeholder Involvement

This study established that stakeholder involvement is important because of the continuation of mental health service provision from the hospital to the community. Jones et al. [44] defined stakeholder involvement as healthcare members who collaborate to work together in providing mental health treatment. Additionally, there is an emerging consensus regarding the involvement of stakeholders in providing mental health care [44, 45]. Various personnel are required for facilitation of the 72-hour assessment, admission, care, and rehabilitation to ensure comprehensive mental health service provision [23, 24]. Among the involvement of stakeholders, the MHCA [17] prescribes that the police, family, MHCPs, the MHRB, and the court must be involved during admission, care, treatment, and rehabilitation in the 72-hour assessment of the involuntary MHCUs. During the admission of violent MHCUs, police can assist to ensure the safety of everyone. The information needed by the MHCPs, such as residential information, family history, and the mental background of the MHCUs, must be provided by the family [23, 24]. Conversely, the MHCPs are needed to assess and be available during treatment and rehabilitation provision during the MHCUs’ stay in the hospital. Before the conclusion of the admission of the MHCU to a psychiatric hospital, the MHRB members are required to check the 72-hour admission forms to ensure that the information is complete and the MHCU is indeed viable for admission to a psychiatric hospital [23, 24]. These forms will be submitted to a court of law for verification and for confirming that the MHCU must be admitted to a psychiatric hospital as suggested through assessment and in writing by the MHCPs and the MHRB [23, 24].

Members of the multidisciplinary (MDT) meetings ensure proper admission and assessment of the MHCUs, as care provided can be shared among them. According to Mpheng et al. [23, 24, 46], MDT members are defined as MHCPs necessary for caring for the MHCUs. For involuntary mental health assessment and treatment provision, the multidisciplinary members must include professional nurses with basic or post-basic psychiatry training, medical doctors, and psychiatrists, including the HHE. During instances when the MHCU is violent, Section 40 of the MHCA [17] permits the MHCP or community member to inform members of the South African Police Services. The prescription is that the police officers must support the local community in instances where the MHCU is aggressive and uncooperative, to ensure the safety of the MHCU, the surroundings, and those around them at the time of the mental health breakdown incident [17, 23, 24]. Additionally, participants in this study encourage support for the safety of the MHCU. They shared that the security personnel must also be involved during the implementation of this model [47], since it is believed that involvement of the security personnel will ensure safety of the MHCUs and the MHCPs during admission in the ward [47]. Furthermore, the safety of MHCUs in the community must be prioritised through community empowerment and education initiatives, such as outreach programmes, as part of continued care [23, 24, 39, 44]. The need for health investors is a priority for development matters, retention and recruitment, and empowerment of the community, including the provision of adequate resources, such as 72-hour designated facilities [23, 24]. With an adequate budget supplied by health investors, the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs might be improved [11].

3.3.4.3. Family and Community Empowerment

This study verified the importance of family and community empowerment. Ong et al. [48] supported this, that families and the community are vital to the care of MHCUs [48]. Additionally, families and the community spend more time with MHCUs; hence, there is a growing expectation that they take on more care of the MHCUs [23, 24, 48, 49]. Furthermore, the WHO [49] and Mpheng et al. [23, 24] indicated that easy facilitation of mental health treatment is promoted by family members and the community, who assist the MHCUs in accessing mental health services and staying compliant with their mental health treatment [49]. Hence, the family and community need continuous health education and support groups to scaffold their tasks. Furthermore, Muddle et al. [39] reported that there is evidence supporting the notion that improved mental health outcomes are achieved in MHCUs when families engage in mental health rehabilitation. Hence, this study promotes and encourages continuous community outreach programmes, such as family and community education.

3.3.4.4. Provision for 72-hour Designated Facilities

This study established that 72-hour designated facilities are essential for the ultimate provision of involuntary admission, care, treatment, and rehabilitation of involuntary MHCUs. The 72-hour health facility must be designated as per infrastructural requirements for admission of vulnerable MHCUs admitted under 72-hour assessment [23, 24]. The MHCA [17] outlines the 72-hour designated facilities as health structures that make provision for proper sanitation, good ventilation, enough space, and proper security for the safety of involuntary MHCUs. Additionally, the 72-hour designated facilities are required to ensure effective and ethical management of mental health provision to the involuntary MHCUs, with proper restraining and seclusion rooms to accommodate the vulnerable involuntary MHCU during their aggressive state [23, 24].

3.3.5. Dynamics: Which Sources Influence the success of the PM?

Dynamics are the determining factors that culminate in a successful PM [27]. The term dynamics in this study refers to the actions that ensure the proper implementation of the policy guidelines on the 72-hour assessment of involuntary mental health units in SA. In this study, dynamics should apply through ensuring accessible mental healthcare services and improved and adequate infrastructure. With improved and adequate infrastructure, support from collaborative partnerships, and trained administration support, the agents can ensure proper facilitation of care and the administration process, which will direct mental health care towards the anticipated quality.

3.3.5.1. Improved and Adequate Infrastructure

This study showed that there is a need for improved and adequate infrastructure. According to Samartzis and Talias [50], improved and adequate infrastructure is defined as the process of creating and improving physical buildings to accommodate the MHCU, with adequate bed occupancy, enhanced security, and a comfortable environment. Malm [51] stated that facilities for 72-hour assessment must be beneficial to the MHCUs and their family members. The environment for admission must be conducive to promoting healing, regardless of the presence of restraining and seclusion rooms [23, 24]. Additionally, the recommendation is dedicated to prioritising the improvement of mental health services through adequate infrastructure, ensured access, healthcare facilities, and quality services [23, 24, 52]. Furthermore, as recognised in the results of this study, involuntary care is provided for the MHCUs in inappropriate environments [23, 24, 53]. According to the MHCA [17], the infrastructure must have proper sanitation, good ventilation, and lighting. In addition, safety and security must be ensured through a secure perimeter wall, and access to the facility must be security-controlled “with allowance for accessible observation”, with consideration for the privacy of MHCUs. The participants in this study also shared that there must be enough beds and a safe space to move freely within the facility.

3.3.5.2. Collaborative Partnerships

This study showed that there is a need for collaborative partnerships. This is supported by Angiuli [54], who defines collaborative partnerships as comprehensive mental health care for emergency response, with support from mental health practitioners' inclusion of other parties, such as legal assistance and community involvement. For implementation of the study’s PM, the MHEs regard the collaborative partnership members as the MHRB, legal support, and the home-based personnel. As part of collaborative partnerships, the MHRB should ensure proper facilitation of implementation documents and maintain positive links with the high court as well as the HHE [23, 24]. They must also always act as advocates for the MHCUs [13, 24]. Additionally, there must be legal support by the court for a timeous response to the MHRB, for assurance of a reasonable response following checking and verifying documents for admission of the MHCU, to maintain proper implementation of the steps around involuntary MHCUs [24, 34, 35]. As part of the continuation of care in the community mental health setting, there must be trained home-based personnel to provide support to the MHCUs and their families in ensuring that the MHCUs adhere to their mental health treatment, including follow-up for rehabilitation purposes [49]. This study encourages the involvement of home-based personnel for diligent compliance with appointments and treatment adherence by the MHCUs when they are discharged into the community [46].

3.3.5.3. Administrative Support

This study encourages administrative support. The South African Human Rights Commission [55] promotes this support, arguing that it is required to ensure ongoing assistance for continuous correct processing of documentation from admission to discharge of MHCUs. In terms of the health policy makers and health care systems, available administrative support must be enforced to ensure ethical management of documents. Additionally, trained and adequate secretariat staff should be made available to facilitate the proper processing of MHCA forms, from the mental health care practitioners (MHCPs), to the HHE, and ultimately to the court for evaluation [23, 24]. That should inform correct decision-making regarding care of the MHCUs when they are admitted for 72-hour assessments or discharged.

3.3.6. Terminus: What is the End Point of Activity?

Terminus, according to Dickoff et al. [27], refers to the end or finish point of a said activity. In this study, the terminus refers to the end point of a PM. The term refers to the effective and proper implementation of the policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCU in SA because of the established PM. Through the implementation of a newly developed PM, there must be evident proper implementation of the 72-hour policy guidelines, related to accessible quality mental health service, including availability of competent staff members [39]. The MHCUs must receive quality health care as advocated for by the MHCPs and the MHRB [13, 23, 24]. The actions outlined in the ‘Process’ and ‘Dynamics’ of the PM must apply during admission, care, treatment, and rehabilitation of the involuntary MHCU. Proper implementation of the 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs will lead to the mental stability of the MHCUs, more family time, bonding, and happiness [23, 24]. To reduce the stress and anxiety of MHCUs and their families, there is a need for more family time. This would motivate family members to be at their best and to create a therapeutic environment for the MHCU at home, leading to a healthier lifestyle.

3.4. Practice Model Validation

The following sections present the findings of the validation phase. The validation of this PM was guided by a theoretical framework for professional nursing practice [56]; thus, the presentation of this study’s PM is comprehensive, with clear definitions of the central concepts, and the theoretical foundation of the model is clear and acceptable. The PM in this study describes the characteristics of PMs, compared to the article by Slayter et al. [56]. This study was validated through the e-Delphi technique and presentation at a conference. The feedback from the validation phase was incorporated during finalisation of the PM.

3.4.1. Presentation at a Conference

We presented the newly developed PM at the Southern African Association of Health Educationalists conference held on 25–28 June 2024 at Gateway Hotel, Umhlanga, Durban. The main supervisor of the study was present at the conference for support. Attendees at the conference acknowledged that the proposed PM is comprehensive and promises to strengthen mental health care in 72-hour units. One of the conference attendants asked the researcher to make the PM available to all the provinces in SA. In order to make the PM available across the country, it shall be published as an article and thesis for wider dissemination. It will also be presented at other conferences in the country.

3.4.2. The MHEs’ Validation of the PM

The PM was validated by MHEs, following a series of three e-Delphi rounds. The panel of MHEs used an e-Delphi Likert scale aligned with Chinn and Kramer’s [28] critical reflection questions to assess the PM’s clarity, simplicity, generalizability, accessibility, and importance.

In the first round, the researcher collected the demographic information. The MHEs were provided with information regarding the purpose of the study and what the research is about, and the inclusion criteria of who should take part. MHEs received the PM, which included an explanation/illustration of the draft PM. The MHEs became acquainted with the developed PM and gave individual comments. They contacted the researcher if they needed an explanation of the developed PM. The MHEs worked on the developed PM and provided suggestions and inputs. After completing the materials supplied in the first round, the MHEs returned them to the researcher via email. The researchers worked on the MHEs' remarks after the first e-Delphi survey round.

In the second round, the 21 MHEs received feedback from the researcher. The researcher clarified concerns raised by the MHEs related to shared responses and provided concept definitions as requested by the MHEs. The participants were given three weeks to respond to the researcher. Consensus was not reached in the second round as MHEs believed that MHCPs required to execute the PM must be clearly elaborated, as illustrated by the following excerpt: “I suggest that the agents of the model be specific, example: not all professional nurses can be agents, but only those with mental health background and specialization are relevant agents, whereas those professional nurses who do not have psychiatry as a qualification cannot be the relevant agents.”

In the third round, the long question ‘What would you like to add to the practice model and why?’ received the following response from one of the specialist psychiatrists: “Human resources is an important part of the dynamics” (MHE SP 1). One of the MHEs, who is a psychiatric nurse specialist, said that she has “Nothing to add. I think the model will be useful. And, with all the information and explanations regarding dissemination of information, it is clear that the model will be accessible” (MHE PN 4). The MHEs are satisfied with the developed PM and anticipate progress and success regarding its implementation at the 72-hour assessment units. The MHEs acknowledged that the PM model could be beneficial and valuable to strengthen the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in South Africa. The final e-Delphi results were analyzed to accomplish the purpose of the study. The MHEs concluded the end point of the PM as sufficient to ensure “the effective and proper implementation of the 72-hour policy guidelines leading to the provision of quality and ethical management of involuntary MHCUs”. The MHEs received a summary of the results and were satisfied with the developed and validated PM. The PM complies with the criteria for model validation according to Chinn and Kramer [28].

3.4.3. How Clear is the PM?

The PM's clarity is defined as semantic clarity, conceptual consistency, structural clarity, and structural uniformity. The panel of MHEs who validated this model indicated that it was structurally uniform and that the concepts were comprehensive. The MHEs acknowledged that the PM is not too complex and that it is clear to follow.

3.4.4. How Simple is the PM?

The MHEs indicated that the PM is simple based on the topic, purpose, and activities carried out to achieve the PM’s objective. They shared that the model structure and components are clear. Simplicity for this model means that the embedded concepts are kept to a minimum.

3.4.5. Could the PM be Generalized?

The MHEs suggested that the model was sufficiently general for its intended goals. Generalizability for this PM refers to its relevance and applicability across various settings and areas of practice. The MHEs believe that the model can be applied for implementation for MHCUs other than involuntary MHCUs.

3.4.6. How Accessible can the PM be?

The MHEs agreed that the PM is accessible. Accessibility refers to the extent to which empirical characteristics may be identified, as well as the extent to which the model's goal is achieved. It will also be accessible to the head of the DoH, as well as the designated 72-hour health institutions.

3.4.7. How Important is the PM?

All the MHEs concur that this PM is important. This PM's importance is described by its clinical significance and practical importance for the purposes of psychiatric nursing practice, research, and education. The significance of the PM is notable to the MHEs, and they acknowledge that the PM yields positive outcomes for the involuntary MHCUs. The components of the PM will constantly affect one another in real-world contexts; for instance, agents may modify their strategies in response to input from recipients or infrastructural constraints, which in turn affect procedures and outcomes. Emphasizing these feedback gaps and interdependencies will highlight the PM's flexibility and establish it as a responsive framework appropriate for complex and changing environments. The MHEs acknowledge that the PM model will be beneficial and valuable to strengthen the implementation of policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA.

4. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

While the study was limited to the North West, Gauteng, and Northern Cape provinces, the development and validation of the PM were based on a qualitative exploratory descriptive and contextual research design. Thus, the process of developing and validating the conceptual framework was described in detail with a broad description for the readers.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the validated PM offers a practically structured framework for improving policy recommendations for the 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA. The PM aims to strengthen the implementation of policy guidelines on the 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA. The developed PM provides sufficient guidance to health professionals in 72-hour admission hospitals. The model's clarity, usability, and applicability to clinical practice were confirmed by expert consensus established using the e-Delphi approach. This PM is now available, and consensus with the MHEs was reached in the third e-Delphi round. This PM makes a significant contribution to the discipline of mental health and psychiatry and may improve the quality of mental health care, treatment, and rehabilitation services of the involuntary mental health care users. The PM is made up of the process that advocates and promotes training and development, stakeholder involvement, the recruitment and retention of competent staff, family and community involvement, and the provision of specified facilities for 72 hours. The dynamics include enhanced and appropriate infrastructure, collaborative partnerships, and administrative support. The findings of this study suggest that the PM has the potential to help healthcare practitioners comply with policy requirements and improve adherence in mental health assessment settings. As elaborated, the model of this study is aimed at strengthening the implementation of 72-hour policy guidelines on 72-hour assessment of involuntary MHCUs in SA.

RECOMMENDATIONS

It is recommended that the PM be adopted and implemented by all mental healthcare facilities, especially the 72-hour assessment units in SA. It is necessary to prioritize the mental health of involuntary MHCUs to reduce readmissions of MHCUs at the 72-hour assessment units.

EXPLICIT REFLECTION ON THE ETHICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY’S FINDINGS

It is essential to consider the ethical implications of the study's findings because involuntary mental health care inevitably involves complex ethical concerns, especially regarding autonomy, consent, and the use of coercive approaches. The findings drew attention to the potential advantages of structured healthcare processes, as well as the possible consequences of hindering service users' autonomy. This brings up significant ethical concerns on how to maintain a balance between respect for individual rights and dignity and therapeutic decision-making. Accordingly, the results support morally ethical practices that include an emphasis on openness, collaborative decision-making where feasible, and ongoing review of the integrity of coercive measures.

To enhance the PM’s application value, the PM might be put into practice. To determine the PM's effectiveness and influence and impact on decision-making, a pilot program might be conducted in a few hospital settings. Alignment with present health system structures would be supported by integration into existing treatment pathways, such as staff training programs and interdisciplinary team meetings. The PM's components might be efficiently addressed with support from the DoHs from different provinces.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

| DoH | = Department of Health |

| FGDs | = Focus group discussions |

| HHE | = Head of health establishment |

| MHCA | = Mental Health Care Act |

| MHCPs | = Mental health care practitioners |

| MHCUs | = Mental health care users |

| MHEs | = Mental health experts |

| MHRB | = Mental Health Review Board |

| PM | = Practice model |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the Scientific Committee of the School of Nursing Science and the North-West University Health Research Ethics Committee (NWU-HREC Reference Number: 00032-23-A1). Human participant-researcher relationships in this study were conducted according to the DoH’s Ethics in Health Research Guidelines, as revised in 2015.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. From the empirical phase of this study, all participants voluntarily signed the informed consent forms.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author [OI] upon request.

FUNDING

This study is funded by the North-West University postgraduate and Health and Welfare Sector Education and Training Authority (HWSETA) bursaries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors sincerely appreciate the support of the management of health facilities, health departments, study participants, independent reviewers, the co-coder, and the language editor in conducting this research.